THE GAMBIA

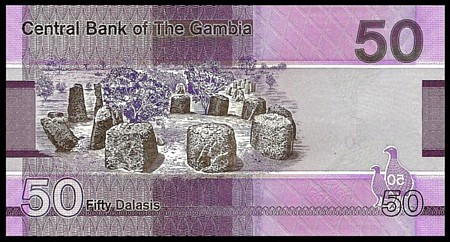

Wassu Stone Circles

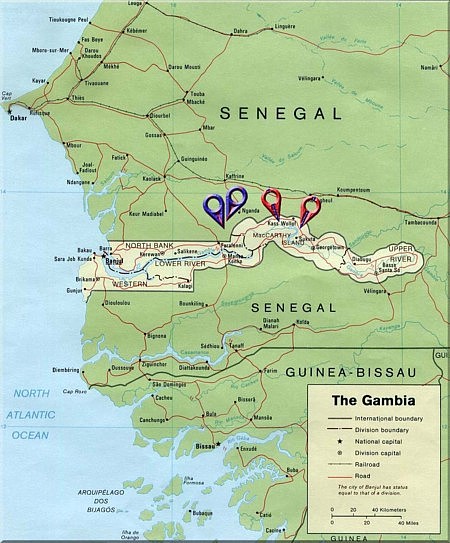

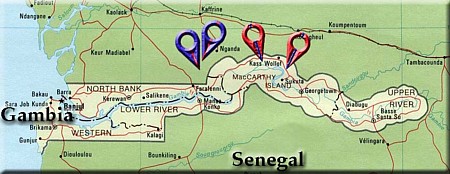

The Gambia is a country in the North-West protrusion of Africa. To its west is the Atlantic Ocean, but it is surrounded on the North, East and South sides by another country, Senegal. The Gambia is the smallest country on the African mainland, only about 30 miles wide at its greatest width, and around 295 miles long (48 km wide and 475 km long). The country is effectively bisected along its entire length by the Gambia River. The area of Southern Senegal and The Gambia has also been known as Senegambia, a name which refers generally to the region and predates the defined countries. Curiously, while Senegal is part of the West African States and uses their currency, The Gambia does not. Currently (July of 2020), the exchange rate between The Gambia and Senegal/W.A.S. is: 1 GMD = 11.2971 XOF.

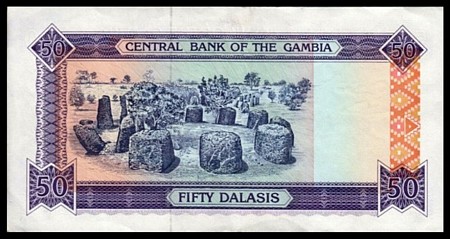

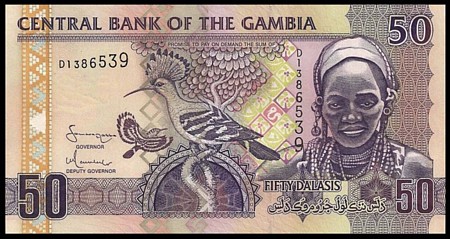

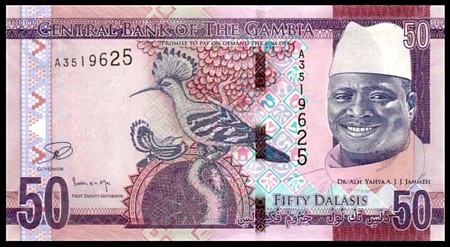

Because it maintains its independent currency, The Gambia is able to highlight some of their own national identity and history on their banknotes. While Senegal shows its position in a currency union and general African symbology, The Gambia highlights specific leaders, society, wildlife and culture. One of the more remarkable symbols on The Gambian currency is on the 50 Dalasi banknote: a set of stone circles located in Wassu, one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

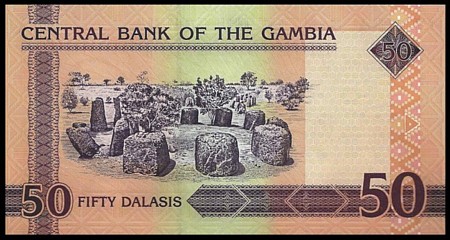

Along the north-central part of The Gambia, where the river and the country arch northward on the map, there are two UNESCO World Heritage Sites within The Gambia, the Wassu and Kerbatch sites, and another two in Senegal, the Sine Ngayene and Wanar, which are further north and west. All four sites are similar in that they have ancient stone circles and burial grounds located just north of the The Gambia River. While there entire Senegambia area has over than 1,000 stone circles and standing stones, they are spread over an area 62 miles (100 km) wide and 217 miles (350 km) long. These four UNESCO sites offer the most concentrated number of circles in the area, with 93 circles.

Each circle has between 8 and 14 stones averaging about 2 meters in height and about 7 tons each. The stones are hewed laterite, a porous, claylike material that is soft when quarried and hardens when it is exposed to the air. Laterite is composed of several minerals and substances and is made over thousands of years of repetitive seasonal wet and dry seasons which aid in the leaching of many minerals. Quartz is the most dominate rock left in the material though composition varies with location and depth of the quarry. The stones used in these sites were quarried just east of the Sine Ngayene site in Senegal. The exact date of these circles is not precise, with estimates varying from 300 BC. to 1600 AD, suggesting that these stones were being made over a very long time.

When we think of stone circles, we probably think of Northern Europe and the British Isles, with Stonehenge first coming to mind and perhaps some of the smaller stone circles dotted throughout the area. The oldest known stone circle however is located in Turkey at Gobleki Tepe, which has been dated to 9,000 BC. While it has stone circles, its structure is a megalithic circular complex whose use was likely more than what most stone circles were used for. When we consider the more familiar stone circle structures we are familiar with, such as standing stones in a field, the oldest known circle then would be the Nabta Plain in Egypt, dated to approximately 4,500 BC. Nabta was placed on the Tropic of Cancer and as such it is thought to be done intentionally, which lends itself to the idea that it was created for astronomical use.

The Senegambia sites, though exposed to the surface and not hidden in any way, have remarkably been left to their intended purpose since placement, and only a few have been excavated. These excavations have revealed some burial sites containing bones, iron tools, jewelry and pottery. Some of the graves have been dated with a range of 927-1305 AD.

Though some stones are leaning and others have fallen down, there are very few stones that have knowingly been removed from these sites and it is possible that the belief of the stones having a spiritual influence may be a significant influence on their not being taken and used for other purposes.

The excavations revealed a rather typical burial system within the circles, including single, multiple and mass graves. This indicates the level of status for the single graves while the mass graves suggest epidemics, wars or other catastrophe. Where possible, the stones have smaller rocks placed and even piled on them, similar to how some more modern grave markers are still reverenced today when a visitor will place a stone on a grave.

The two sites in The Gambia are the Kerbatch and Wassu sites, the circles vary between 13-20 feet (4-6 meters) in diameter. At Kerbatch, there are 9 circles, one of which is a concentric circle. There is another ‘bifid’ stone or a V-shaped stone, and it is thought that this may have been a symbol of a type of harp or lyre musical instrument.

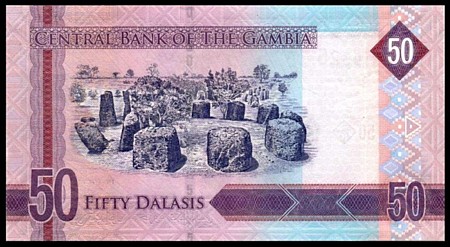

The Wassu site is the furthest east of the four sites and it contains 11 circles and has the tallest stones in all the sites, about 8.5 feet (2.6 meters) in height. It is this site that is commemorated on the back of the Gambian 50 Dalasis banknote.

The construction of these stone circles, as do others throughout the world, gives an indication that the society that prospered here had to be highly developed and organized for an extended period of time. Though the stones could have had many possible uses including astronomical timekeeping for agricultural purposes, their culture at some point also associated the stone circles with the burial of their dead.

There have been four banknote issues which depict the stone circles at Wassu, all of them on the 50 Dalasis denomination and feature the Wassu Stone Circles on back. The first such banknote was issued from 1989-1995 and cataloged as P-15. It featured both the Hoopoe bird and President Sir Dawda Kairaba Jawara on the front and the Wassu Stone Circles on back.

President Jawara was elected as Prime Minister and served from 1962 – 1970 through The Gambia’s independence in 1965. When The Gambia became a republic in 1970 he was elected president and remained so until 1994 when the government was overrun by a coup d’état.

The second note was P-19 and was issued in 1996. It also had a Hoopoe bird on front, and a female depicted on the right. P-23 and P-28 were essentially the same designs with differences in the serial number incorporating an ascending size with P-23 (issued from 2001-2005) and eliminating the white border on P-28 (issued 2006-2014 and 2018).

The third note to depict the Wassu stones was issued in 2015 and was P-34, which replaced the female on the front with then President Sheikh Professor Alhaji Dr. Yahya Abdul-Aziz Jemus Junkung Jammeh (formerly Yahya Alphonse Jemus Jebulai Jammeh) or, as it is spelled on the banknote: Dr. Alh Yahya A. J. J. Jammeh. After a military (though allegedly bloodless) coup, he was president from 1994-2017. Jammeh was a terrible leader who is accused of stealing money from the country, ordering protesting students to be shot in 2000, killing 14, ordered the deaths of migrants in 2005, lead a literal witch-hunt after he suspected his aunt was killed by a witch doctor in 2009, was accused in several rape cases, and many other offenses. Losing the election in 2016 he left The Gambia to live in Equatorial Guinea in exile, along with his pilfered luxury cars and the equivalent of US $54.5 million dollars from the treasury, state pension fund, and various other governmental funds. His reign left the country in excess of US $1Billion in debt.

The latest note to showcase the Wassu stone circles was issued in 2019 (P-New). This note replaced the Hoopoe bird with two depictions of a bird of prey, and replaced President Jammeh with the coat of arms. The vignette of the Wassu stone circles is the same, but offers a narrower view.

Like all stone circles throughout the world we are only making educated guesses as to the real reason for their creation. While some may have been built for a specific use, it may be that some of them had a variety of uses, and the uses may have evolved over the many years since their initial construction. Regardless of their original purpose, the stone circles in the Senegambia region are a unique and fascinating glimpse into a long lost past. As Wassu is such a remote location for most of the world, being able to hold a banknote with the image of the megalithic structures somehow links us to the site and to the people who built it, keeping their history more alive than before.