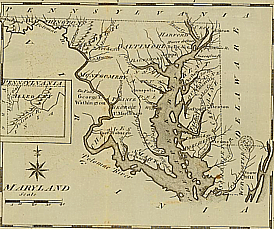

MARYLAND COLONY

William Eddis

In perhaps the greatest detailed account of everyday life in the days leading up to and during the revolutionary war, William Eddis, in his letters home to friends and family, has left open a wonderful portal into the past at the very beginnings of a new country and the end of a career based on the colonial administration of that land. Born 1738, William Eddis was about 31 years old when he decided to venture to the colonies to seek his fortune. But it must be clear, that Mr. Eddis was not going to become an American Colonist. He grew to understand and sympathize with the colonists, but he was a loyal British citizen.

William Eddis arrived in Yorktown, Virginia on August 30, 1769, in route to Annapolis, Maryland. Eddis had accepted a position to work for the Colonial Maryland Governor, Sir Robert Eden. Eddis was to be employed as the Surveyor of Customs. Arriving in America, he begins his first letter home. In it, it is apparent that he had made a prior arrangement to write back frequently during his time abroad. In his first letter, William Eddis states to the recipient that he will “Occasionally transmit what may be supposed naturally to suggest itself to any indifferent spectator, whom curiosity or amusement has carried into a distant country.” Unfortunately, in these letters, the recipient is almost never known. Occasionally the language is such that we can ascertain that the recipient is his wife, but most seem to be to some other friend, of which he seems to have had quite a number of. There are often several dated entries to one letter, reporting back the various activities that were in his sphere during the time. Some of the observations are on cultural aspects, such as his astonishment that while in England, almost every county has its own accent and unique dialog, while in America, the manner of speech is consistent throughout the colonies. Of course as it goes on, the majority deals with the political news.

In speaking about the colonists, Eddis writes in his second letter, dated October 19, 1769, an impression that is very telling of things to come: “Almost from the commencement of their (Colonists) settlements, they have occasionally combated against real, or supposed innovations; and I am persuaded, whenever they become populous, in proportion to the extent of their territory, they cannot be retained as British subjects, otherwise than by inclination and interest.”

Less than two months into his stay in America, Eddis relates that there are fanatics who talk of hostile measures because of government duties on “Other Articles” which were placed after the repeal of the stamp act. This in effect nullified the stamp act repeal, and it wasn’t sitting well with the colonists.

In this same letter, he also makes an interesting observation of payments not only with money, but with goods: “By the laws of this province, all public dues are levied by a poll-tax. The clergy, from this provision, are entitled to forty pounds of Tobacco for every person within a limited age, at the rate of 12 shillings and six-pence per hundred-weight. Persons who plant tobacco have it in their option to either pay either in money or in produce; those who do not, are consistently assessed in specie.”

In his fourth letter dated April 4th, 1770 William Eddis notes that “to establish a hierarchy would be resisted with as much acrimony as during the gloomy presence of the puritanical zeal.” He goes on to state that it wasn’t always so here, and that he believed that “…Before the colonies had arrived at their present degree of population and consequence: Had an order of nobility been created, and dignitaries in the church appointed at an early period, it would most assuredly have greatly tended to cherish a steady adherence to monarchical principles; and have more strongly riveted the attachment of the colonies to the parent state.” The parent state, of course, being England.

As it then rested, however, “A republican spirit appears to predominate; and it will undoubtedly require the utmost exertion of legislative wisdom, to establish on a permanent basis, the future political and commercial connection between Great Britain and America.”

Having spent a few months in America, Eddis has come to know the colonists better. He was working for the Crown, but in effect, his welfare was in the same boat as the colonists. In his 5th letter dated June 8th, 1770, Eddis makes comment on dealing with the acts of parliament against trade and goods in America; he writes: “It is with the utmost concern, I am necessitated to acquaint you, that a spirit of discontent and opposition is universally predominant in the colonies.”

15th Letter January 3rd, 1774

Here Eddis makes a reference to the news of the Boston Tea Party. “…The whole quantity of tea, contained onboard three vessels, amounting to three hundred and forty-two chests was on the 16th of December , immersed in the bay. The East India company are the only sufferers on this occasion; as all accounts perfectly correspond in asserting, that this hasty business was transacted without the least detriment to private property.”

He further states that: “Vast as this continent is, the inhabitants appear animated, to a degree of frenzy, with the same spirit of opposition. Where the consequences will terminate, Heaven knows! If a judgment may be formed from the present disposition of the people, I will venture to assert, that not the least future taxation will ever be admitted here, without what they conceive, a legal representation.”

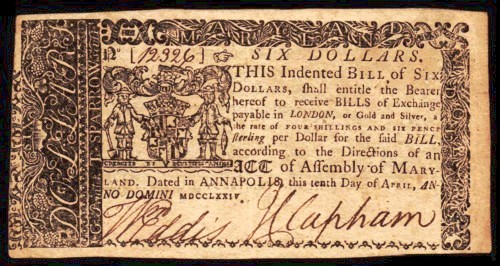

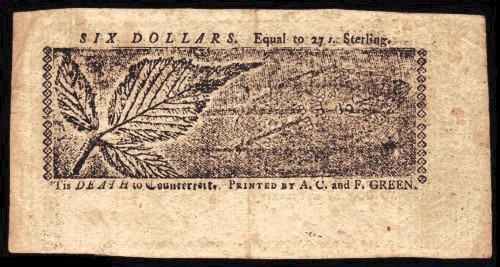

April 10th, 1774 – This particular Six Dollar banknote with the signatures of William Eddis and John Clapham was issued.

In his 17th Letter dated May 28th, 1774, Eddis pens “All America is in a flame!” describing the fervent feelings of the colonists as they make their desires for liberty known. Eddis keeps this fiery metaphor going in his next letter dated October 26th, 1774 “The spirit of opposition to ministerial measures, appears to blaze steadily and equally in every part of British America…”

He also mentions that large amounts of money are being spent on military weapons and that “…persons of all denominations are required to associate under military regulations.” Here, he means that military service is becoming mandatory, regardless of one’s position.

Letter 20 April 26th, 1775 Pg. 202

Eddis sends home a report that on the 19th of April, 1775, British troops attacked provincial Militia in Lexington, Virginia. This is the first time Eddis writes of actual hostile actions.

On May 3rd, 1775, William Eddis relates his experience with power and corruption, mixed with hypocrisy. He has found that even when the cry for freedom is loud and clear, there are those who would take advantages of it.

“I am heartily disgusted with the times. The universal cry is ‘Liberty’ to support which, an infinite number of petty tyrannies are established, under the appellation of committees; in every one of which a few despots lord it over the calm and moderate; inflame the passions of the mob, and pronounce those to be enemies to the general good, who may presume any way to dissent from the creed they have thought proper to impose.”

In his 21st letter dated July 25th, 1775 he makes a remarkable statement that is anything but what we would consider to be our modern idea of liberty. “Speech is become dangerous; letters are intercepted, confidence is betrayed, and every measure evidently tends to the most fatal extremities.”

He also reports briefly on the incident at Bunker Hill, where “Provincials were forced from their entrenchments, but it is said the (British) regulars suffered so severely, that they cannot afford to obtain future advantages at so dear a price.”

Continuing on, he reports that the colonists are under a veritable martial law and that while many are required to participate in the militia, “I have not yet, in positive terms, been required to muster; and, I trust, my peculiar circumstances will be considered as a reasonable plea of exemption.” This is an important paragraph, as he outlines his position and feelings toward America and his position and loyalties to the Crown, when he further states: “I wish well to America. – It is my duty – my inclination – so to do – but I cannot – I will not – consent to any act in direct opposition to my oath of allegiance, and my deliberate opinion.”

Letter 22 August 24th, 1775

Given the position of his office, Governor Eden and his household have been exempted from enrolling in the militia. In order to keep William from performing duties which would be in direct violation of his sworn duty to the crown, William is brought into the Governor’s household. Under these ever tightening requirements and the sense of impending war, Eddis’ wife sets out to return to England. Still, in this letter to an unmentioned friend, Eddis is able to write about the current fiscal matters plaguing the colonies: “A new emission of paper currency, to the extent of 60,000 pounds sterling, is now preparing under the inspection of gentlemen, appointed by authority of the Convention, which is hereafter to be sunk by a tax on the inhabitants of this province; besides which they are to be assessed their proportion to sink the congress money, amounting to 675,000 pounds, lately emitted at Philadelphia, for the payment of the provincial army. How these enormous expenses are to be supported, and how the people are to be maintained, after a total stagnation of commerce, is not was to conceive. If ways and means are not speedily devised to feed the hungry, and clothe the naked, we must assuredly experience all the horrors of the most extreme indigence.”

Letter 29 May 20th, 1776

Eddis reports that the Continental Congress has recommended to the individual colonies that they recommend that the colonies “Adopt government as shall in the opinion of the representatives of the people best conduce to the happiness and safety of their constituents, and America in general.” According to his letter, “Virginia has taken a most decided lead in promoting a total separation from Great Britain” with its own declaration. In it they declared the colonies “Free and independent states, absolved from all allegiances to, or dependence upon the crown, or parliament of Great Britain.”

May 24th, 1776

Eddis writes home that Governor Eden has been ordered to leave the colonies, and will only be allowed to return when “The unhappy disputes, which at present prevail, are constitutionally accommodated.” William Eddis’s employer requires him to remain in Maryland, and continue his job. William at first wonders how he is to conduct himself in this situation, but then finds resolve and states: “Whatever may be the complexion of my fate, I will continue to act consistently with what I conceive to be my duty.”

As time went on, we can see that while Eddis steadfastly remained a loyal British citizen, he held no ill will towards the Americans: “I therefore trust it will be ever my disposition to judge in the most favorable manner of my fellow creatures, and acknowledge every man to be right, whose conduct is directed by the conscientious dictates of his breast.”

On June 1st, 1776 Eddis discovered that he was mistaken to believe that he would continue to be excused from participating in militia duties due to his position and connection to the exiled governor, and has been fined 10 pounds and was ordered to surrender all of his arms.

Letter 30 June 4th, 1776

The ‘Committee of Observation’, one of those infamous committees Eddis wrote about on May 3rd, 1775, was originally meant to be a group to watch over the royalist government actions. But even so, the local militias were generally under their control. As time went on, these committees became the local government when the British authorities were expelled from their positions. The one in Maryland by this time had summoned William Eddis to appear before them in order “to give security for my behavior during the present unhappy contention with great Britain. I must either comply; submit to imprisonment; or abandon the country.”

June 10th, 1776

Eddis sends home a transcript of what he will present to the Committee of Observation, outlining the reasons that he and his partner will need to remain in America as subjects to the crown to fulfill their duties to Great Britain and the local populace by bringing to an end the fiscal transactions between them. The second party with whom he will be presenting this is John Clapham, who is the second signatory on this banknote. Eddis refers to him here simply as his associate. In this document, they will ask the ominous sounding Committee of Observation to allow them to leave the country, but only after they have been able to settle the business of their loan-office, which was of great concern to the community.

Eddis also notes in this letter that his associate, John Clapham, was in such a position that he could ill afford to lose his employment and be forced to return to England with few possessions. Already having a large family, his wife was pregnant again. Clapham would not have been able to sell any of his property or possessions due to the political uncertainty and looming war causing everyone to hold onto their money. Adding to that, Eddis states that John Clapham was, like Eddis, a man of principle and would not cut and run to protect his own at cost to his employer – the crown.

June 11th, 1776

The committee of Observation orders Eddis and Clapham to leave the province by August 01, 1776 or be fined 10,000 pounds. Scant time to settle all the business they have. “I shall establish my temporary residence with my worthy colleague (Clapham) and his family and with them shall probably bid adieu to Maryland.” Wishful thinking for William Eddis.

Letter 31 July 2nd, 1776

Eddis and Clapham are running closer to the deadline imposed on them by the Committee of Observation. They are going to ask the committee to allow them an extension to complete their duties.

July 8th, 1776

William Eddis writes that “The Colonies, by their representatives in Congress, are declared Free and Independent States” on the 4th of July, 1776. Eddis contemplates the “Miseries which appear ready to overwhelm this country”, and relates the Provincials victory in a battle in Charlestown, South Carolina on the 28th of June. Eddis asks when he will hear from his family, as “To remain thus ignorant of the situation of my family, is a weighty addition to the complicated evils I encounter.”

Letter 32 September 5th, 1776

On 22 Aug 1776, the British troops landed on Long Island, and on the 27th of August, 1776, they defeated the provincials and General Washington retreated to New York.

September 25th, 1776

Reports that New York has been taken by the British but that the provincials are not deterred in their spirit or determination.

October 1st, 1776

Though their stay to finish the work is extended, Eddis is anxious to receive a “discharge from employment of so much importance to the community.” And reports that the Clapham’s are moving from Annapolis to a house six miles outside of Baltimore in a place called Hunting Ridge. Eddis will be joining them, and as it is 30 miles from Annapolis, he and Clapham will alternate working in Annapolis every other week.

Letter 33 January 1st, 1777

Eddis tells of the Provincial Militiamen leaving as soon as their enlistments are up. Shorter enlistments are proving to be troublesome, and the Americans are forming a regular army, complete with enlistment bonuses for enlisted men of 20 dollars for a three year enlistment. If they stay the duration of the war, they are also to be awarded 100 acres of land. Officers will be compensated at levels appropriate to their station.

Eddis and Claphman are “Not yet superseded in our provincial employment; but the day is assuredly at hand.” Eddis hopes that he will be reunited with his family by early summer 1777.

Due to the British leaving open the ports in Virginia, there has been a brisk trade between Virginia and Maryland, and with the French and Dutch Islands. But wartime inflation has taken hold and “The exorbitant price of almost every essential article exceeds credibility. Those few who are in possession of specie, do not permit it to circulate; and the constant depreciation of paper currency, baffles every attempt of the legislature to support its credit; yet, in spite of apparently insurmountable obstacle, the utmost alacrity appears for the prosecution of the war; and the most sanguine hopes are evidently entertained, that the political connection between Great Britain and America, is finally and effectually dissolved.”

Letter 34 April 2nd, 1777

Eddis and Clapham are at last “superseded in our department as commissioners of the Loan Office” but will have to wait until an investigation of the accounts and transactions by congress. He worries a little about how he will be able to afford passage to England via the West Indies, and applies for a passport to go through New York, but, as feared it is rejected.

May 1st, 1777

Eddis has left Hunting Ridge and is in search of passage from America. John Clapham stayed in Hunting Ridge with his large family and, while Eddis hopes him well, he wonders how Clapham will manage with such a large family to care for in these troublesome times.

June 4th, 1777

Eddis had no way of paying the passage to Europe via the West Indies, and once again applied for permission to enter the British Lines and secure passage from New York. He even considered to be requested as a prisoner on parole and to remain in Philadelphia until he can be exchanged with an American Prisoner.

June 6th, 1777

His request is denied, and Eddis is headed to the French Islands, then onward to Kingston, Jamaica. Or so he thinks.

Letter 35 July 2nd, 1777

Eddis relates his troubled journey, where his ship was deterred by an ensuing battle between a British ship and an American Sloop, upon which they hid in an American port, but were stuck there as British ships were abundant in the area, and the cargo on Eddis’ ship would be confiscated if they were stopped. Eddis appealed to an American officer for assistance, and the obliging American told Eddis to make his way to Hampton, where he would be able to obtain passage with others who were leaving America and returning to England.

Eddis then left in an open boat and made his way to Hampton, but a storm approached and caused him a delay. This storm evidently also caused the ship he was hoping to get passage on to leave early.

Again Eddis appealed to the military commander and received assistance. He was granted permission to find passage on a ship and was told that he would have an officer escort him to the ship in order to authorize his passage. Three days later, he had found passage and while being escorted, a storm again rose, and the escort refused to accompany Eddis until it had passed, and would not give Eddis his passport. Frustrated, Eddis later went to the port alone and asked when the ship might sail. He was told to be on board by dawn as the ship might be able to leave at that time.

Eddis returned to his escort, but his escort had news of his own – the battalion in Hampton was to join with General Washington in the morning and in light of this, the officer could not let Eddis leave America. The officer then Hampton and took Eddis’ passport with him.

Eddis then returned to the port, and availed himself to the ship’s captain, but the captain would not accept Eddis without a passport, as the captain could then be arrested. Eddis did convince the captain to meet with some acquaintances who gave the captain every assurance that the circumstances were just. The captain then agreed to take Eddis onboard at dawn. After a long, apprehensive night, Eddis finally boarded the ship and set sail.

Letter 36 July 3rd, 1777

Two British ships were sighted and they made way for the closest one, on which to deposit Willliam Eddis.

More troubles arose! The wind died. They could not make their way toward the British vessel. The captain conceded defeat and, with the wind now toward the West, decided to make way to the harbor again. Eddis was mortified and pleaded with the captain to try for the other vessel. The captain refused and aimed for Hampton. Eddis was not sure what to do, but he somehow convinced the captain to anchor along the shore, hidden from view of the ships and Hampton and to try again in the morning.

Passing another restless night, Eddis greeted the morning and a fresh wind. Making way, they were within 2 leagues of the ship when the wind reversed and the seas began to churn. Eddis promised the captain more money if he were to get him to the ship. The promise of money worked, and the captain promised to do his best to get him aboard the British Vessel. The stormy seas and lack of wind made progress painfully slow for the eager traveler.

Then, as luck would have it, an American Schooner was seen in route to Eddis’ slow moving ship. But the wind picked up again and Eddis was soon alongside the British Frigate. But the seas were still churning enough that they made the handling of Eddis’ ship unwieldy and their movements were not making the British happy. They were ordered to lay anchor and to send a party to the frigate. Unfortunately they had no speaking tube, and their anchor was inadequate. Further, they had only one canoe which could only safely take one person at a time. All this while, the American Schooner was just out of range, watching.

The captain of Eddis’ ship embarked on the canoe, but the sea being so agitated, it took an hor for him to board the British frigate. Moments later, Eddis saw the British launch a boat and he was soon offered an invitation to take passage on the frigate.

Letter 37 July 5th, 1777

Safely onboard the HMS Thames, Eddis soon learns that he is well known amongst the crew. It so happened that this vessel had taken an American ship and gone through the letters, hoping to get some intelligence from them. With these letters were two of Eddis’ own, and upon reading them, the officers were so impressed with his character portrayed, that they kept them and sent them along on the next ship bound for England.

Eddis stayed on the Thames until June 27th, 1777 when he was transferred to the HMS Emerald, which could more readily transfer him to New York where he could find a ship bound for England.

July 19th, 1777

Eddis has finally made his way to New York, which was then still under British control. Feeling safe, he has meet with several acquaintances, and in this letter he tells his wife that “I am now free, unawed, unrestrained. – I feel myself enlarged; and I will write, speak and act, as becomes a zealous adherent to the British constitution.”

Letter 39, august 16th, 1777

Eddis is waiting his time in New York for a vessel to sail to England and take him home. He stayed with friends and wrote of the city to his wife, describing the buildings, streets, etc. and how the provincials set fire to the city when the British were taking it, destroying at least one – third of the city.

Here he also comments on the Wartime inflation and the exorbitant prices. He also tells her of the large lobsters that were once caught in great numbers there, but that due to the cannonading, the lobsters have left the area and not a single one has been caught or even seen since the hostilities began.

September 6th, 1777

Sadly, Eddis wrote his wife: “It is confidently reported, that the city of Annapolis, the scene of our former happiness and prosperity, is reduced to ashes.”

Letter 40 September 20th, 1777

Eddis was able to tell his wife a bit of good news – that the reports of the burning of Annapolis was false and that the city was unharmed.

November 1st, 1777

Again, Eddis was hoping to set sail from America to rejoin his family. He has booked passage on a ship sailing to Cork, Ireland, and hopes to be in England before the New Year. He cannot afford the passage due to the elevated cost of provisions in wartime, so he has been given the provisions by his friend, Daniel Chamier, Esq., with whom he was staying. Eddis was of course very grateful.

Letter 41 December 16th, 1777

Eddis has arrived in Ireland and is writing from Cork. He had (for Eddis) an uncharacteristically safe and speedy voyage.

December 25th, 1777

Now in the village of Passage, Ireland and is embarking on a ship to sail to England, Eddis tells his wife that he will post this letter in Passage, Ireland and wonders if he will be home before the letter itself.

Letter 42 December 27th, 1777

At last Eddis had Finally arrived in England. But not in Bristol! Eddis sent this final letter from Devon because, due to a storm, the ship pulled into Devon instead of sailing to Bristol. This close, he was not going to wait any longer, and wrote that he would make the rest of the journey on land.

Eddis Wrote his wife that they should always “look forward with gratitude and confidence.” And that “If adversity should still continue to oppose our best endeavors, we must derive consolation from reflecting that we have acted consistent with the sentiments which we possessed.”

William Eddis remained with his family in England. He published his letters to family and friends in 1769 under the title “Letters From America”. He lived to a ripe old age of 87 when, in 1825, he passed away in his beloved England.