ZAMBIA

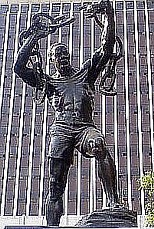

“Chain Breaker” Mpundu Mutembo

(Zanco) Mpundu Mutembo was born March 31, 1934 in the North-Eastern city of Mbala, Zambia, then known as Northern Rhodesia, where evidence of human habitation in that area dates back well into the ancient past before written history.

When he was only 18 years old, Mutembo dropped out of school and joined the political struggle led by the politician Robert Makasa, and it was then that he started writing what would eventually be several books about the damages that colonial administration had on the country.

By 1957 Mutembo had already begun making a name for himself in Northern Rhodesia as an activist for political reform and was quite outspoken against colonialism, for which he had been beaten and arrested by government agents. Because of his commitment to the political struggle, Mutembo was sent to Kenya to assist Dedan Kimathi’s Mau Mau uprising. Dedan had been captured the previous year, and was executed in early 1957 for his armed anti-governmental activities. Seeing a fellow freedom fighter so committed to his cause that he would risk death must have left an impression upon the young Mutembo.

While in Kenya, Mutembo and his companions were tasked with learning how to foment rebellion and then return home and start the process there. It’s unlikely that he learned much about the armed conflict and guerrilla fighting that the Mau Mau uprising had been doing, for when he returned, he worked closely with Kenneth Kaunda (later the first president of Zambia) and Simon Kapwepwe (later the first Vice President), which placed him in a political sphere, not a military one.

Nevertheless, Mutembo is well known for a famous court case concerning a fight about his political views during which he had been sorely beaten and two of his teeth were knocked out. The judge asked him to demonstrate how he was beaten, do Mutembo walked over to the prosecution table, where a colonial lawyer was seated, and punched the lawyer in the face. For his actions, he was sentenced to 10 years in prison, with an additional punishment of four lashes for striking the prosecutor.

Mutembo was held in Livingstone prison, and while there he was reportedly forced to witness the executions of three black men accused of murder. He was later transferred to Mukobeko prison, where he spent the rest of his sentence in comparative peace.

Back in the realm of politics, Mutembo’s role was that of an opening act for the future president. He would go out on stage before Kaunda would make an appearance, and fire up the audience by telling them how bad the colonialist administrators were for the country and to rally them to fight for independence that, with Kaunda at the helm, could be achieved.

It was during a formative meeting on October 24, 1958 that the ZANC (Zambian African National Congress) was formed. It was then that Mutembo got a similar nick-name ‘’Zanco’’. But Mutembo was not alone in receiving a new name; a new nation was being formed by these young men, and that new nation also needed a new name. In an interview many years later, Mutembo recalled that Kaunda and Kapwepwe were mulling over a couple of possible names. Inspired by the Zambezi River, “Zambia” was proposed, and soon it was being chanted over and over, and the decision was made. The motto, “One Zambia, One Nation” was also decided at that meeting.

In the early 1960’s, Kenneth Kaunda drafted a letter to then Governor Sir Arthur Benson, asking for a change in the constitution that granted the Colonial Europeans more power in the legislature. Mutembo (Zanco) was tasked to deliver the letter, but when he arrived at the governor’s office, he was arrested and beaten. But by 3:00 pm that afternoon, he was back in Kaunda’s offices where he was given a hero’s welcome. 12 hours later he went to Cairo Road in Lusaka, and climbed a tree with his megaphone. Early that morning he started denouncing the constitution, and demanding it be changed. Police soon arrived and, unable to talk him down, they threatened to shoot Zanco if he did not stop. The threats of being shot were enough, and Mutembo climbed down and was again arrested. The tree later came to be known as the “Zanco Tree”.

Then, on New Year’s Eve, 1963, Mutembo was summoned by Kaunda and was told that he had been chosen to die for the nation. One can only speculate the thoughts and feelings that assuredly rushed into Mutembo’s mind, such as his memory of Dedan Kimathi’s execution in Kenya years ago. Perhaps this gave him the strength to accept his fate. Together with Kaunda, they rehearsed demands for independence that Kaunda wanted him to make to the Rhodesian Governor. There are no records of why he was told this, nor what it could achieve, but he soon found himself in a car with Sir Evelyn Hone, the last Governor of Norther Rhodesia, en route to police headquarters in Lusaka.

Sir Evelyn Hone, a Rhodes Scholar in the Colonial Service, had served in Africa, islands in the Indian Ocean, Middle East, and Central America. He was the Chief Secretary to the Governor of Northern Rhodesia from 1957 to 1959, and had been appointed Governor in 1959. His primary role at the time was to assist Northern Rhodesia to obtain independence without resorting to the armed conflict which had resulted in Kenya. To start off, Hone opened talks with African nationalists, including Kenneth Kaunda, which might explain how his actions have been reported below.

Mutembo was brought into an interview room inside the police station where he was interrogated. He was afterwards taken into another room, this one filled with reporters and photographers standing by. More concerning though was the 18 armed officers lined up, waiting for him. Mutembo was then fettered with a heavy chain, and was given an order to break free from the chain, or to be shot.

Most people would have given up then and there, and waited for the bullets to send him to his death. Breaking a small chain is hard enough, but the heavy chain he was shackled to was quite large. Mutembo however, started to pull. Perhaps he did not want to die without the notoriety that Dedan Kimathi had achieved in Kenya. Perhaps he acted as instructed by Kaunda, after informing him of his fate. Whatever the reason, Mutembo raised his arms and pulled, harder and harder. The photographers started taking photos, and Mutembo continued to pull on the chains. Eventually, the chain broke. The Governor raised his hands in amazement and declared: “You are now the symbol of the nation”.

Then as rehearsed earlier with Kaunda, Mutembo made his demands for independenceto the governor. Oddly, Mutembo was made to swear on a bible and was then taken to the Governor’s palace for four days. He was then driven a few miles away to a house at 6 Nalikwanda Drive, where he spent the next few months, guarded by police, but with a full set of servants to take care of him.

In March 1964, Mutembo was taken to a town called Abercorn, since renamed to Mbala, and given a plot of land to live on at 214, Bwangalo Road, and awarded a lifetime pension. He stayed there until October 17, 1964 when he was flown back to Lusaka, and reunited with Kaunda. Zambia got its independence on October 24th, 1964 with Mutembo attending the ceremony and standing only a few feet from Kaunda and the British representative, Princess Mary (officially, Mary, Princess Royal and Countess of Harewood).

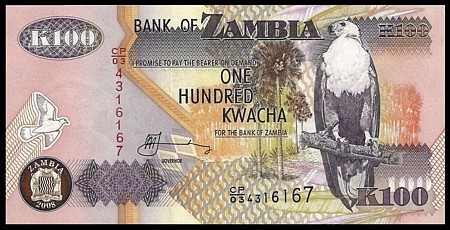

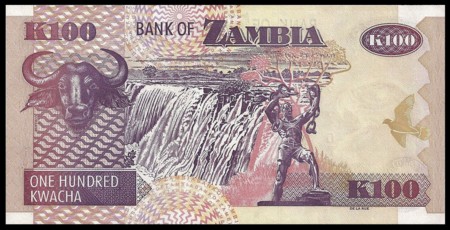

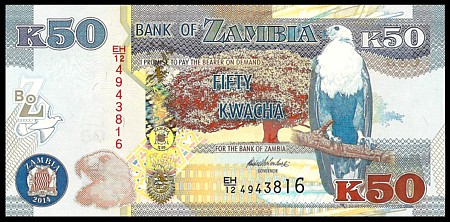

On October 23, 1974, a statue based off of photographs of Mutembo when he broke his chains was unveiled. It has since become the symbol of Zambia’s fight for independence from colonial rule. Many memorials take place for fallen freedom fighters at this statue, and it has been placed on the countries banknotes. Meanwhile, Mutembo donated his land in Mbala to the United Nationalist Independent Party (UNIP) which used it for a while, but it was later turned into a carpentry business. His pension and status also disappeared when Kaunda ceded power in 1991, and today few remember Mutembo’s name or role in their independence.

Mutembo was last known as still working to regain his status and pension returned to him, but has made no progress with the current government. Several articles have been written about him in the local press, yet most are reported as not knowing the name of the man whom the statue was made of. The statue lives on in modern memory, while the man slowly fades away.

There are several things about this story that leave me scratching my head. Most of it is due to the vagueness of the stories available online and in print, and have me asking, “Is this story true?”

It seems really odd that the Colonial Governor would declare Mutembo to be the symbol of the new country. Yet, once we know that the Governor was to assist in the peaceful transition of power, perhaps it isn’t as odd as it first would seem. The manner in which it was reportedly played out, however, is nothing but strange.

In looking at why would they chain Mutembo in the first place leaves us wondering why, if a person was going to be executed, would they need to chain him instead of tying him down, or simply just shoot him? Further, why tell him to break the chain, which would normally be shear folly? Taunting a prisoner isn’t unheard of, but it usually isn’t while a room is full of supposed reporters. While I’m certainly not speaking from experience here, it doesn’t make sense that if you want to kill someone, you offer them an out, and then honor it. It reads like a cheesy novel, having a man bent on killing someone be honor bound by his word. A logical conclusion is that it must’ve all been planned, and that the police were goading Mutembo to try to break the chain in order to make him do so for the reporters.

When we examine Mutembo’s motives, and his mission, it is not beyond suspicion that he was in collusion with Kaunda, and perhaps even Governor Hone, all along to create a national symbol for the budding independence of Zambia. While I cannot state for certain that the story, including the chain breaking, is sprinkled with some untruth or deception, I can’t help being suspicious concerning the lack of specified dates and timelines, and certain odd behavior, especially by the governor after the chain breaking.

My take on this is that Kaunda and his cabinet had decided to fool Mutembo into thinking that he had been chosen to be a martyr for his country, all the while knowing that he would try to pull the chains, which must’ve been carefully altered to make them breakable. By his own accounts, Mutembo stated that he tried very hard, and kept on trying, eventually snapping the chain, to the supposed surprise of all in attendance. To continue the farce, perhaps he was made to swear on the bible that he had done so, which would further cement his conviction that it was real.

It seems that he was then held for quite a while, away from all who would be able to convince him that the chain may have been weakened somehow. His sequestration at this point seems to be something that wasn’t necessary unless they were trying to keep others from interfering in some type of odd con job. Later, he was then given acreage to live on far from the capital, and from those whom he would have had close relationships with. The distance by road between Lusaka and Mbala in 2018 is listed as 636 Miles, or 1024 Kilometers, with an estimated travel time of 14 hours. I’m quite certain it would have taken longer in the 1960’s. It seems odd that the ‘Symbol of the Country” would be placed so far away from those he had worked so closely with, and far from the goings on of a new nation.

Of all the stories I’ve read, most are identical in their chronology, but a bit vague on certain dates. Most suspiciously, while there are many photos of the chain breaker statue, and of Mutembo, there are none to be found of Mutembo breaking the chains in the police headquarters office where he was supposedly about to be executed unless he broke the chains. If the statue was based off of photos, wouldn’t those photos themselves also be famous?

But supposing that the story of breaking the chain is fake, and Mutembo was either fooled or was a willing participant, there is still the question of why it would be done. Would it matter if it was merely an allegorical representation, instead of a real man? In order to push a spirit of unification among the populace, perhaps having a real person embody the strength of the resolve for independence was thought to be a quicker way to unite the people than a statue that merely represents a concept of independent rule without a personal connection. After all, there are 73 distinct indigenous ethnic groups within the Zambian border. The statue depicting a man breaking the chains of colonial oppression serves its purpose to embolden the people with the strength of national unity and pride. But as a statue of a real man, now mostly forgotten, it serves as a proxy for each of each and every Zambian citizen’s personal break from foreign rule.

Whether it is accepted as told, and we ignore the apparent holes in the story as evidence for a faked sequence of events, or draw the conclusion that the whole scene was scripted and sold to the Zambian public, is there any real impact or is it rather a moot point at this time? I am reminded that in the United States there is a story of a young George Washington cutting down a cherry tree and, when confronted, was so honest that he admitted that he was the one who committed the deed. The story was made famous after Washington’s death on December 14th 1799, by Parson Weems in his book The Life of Washington, first printed in 1800 and reprinted in 1809. Parson Weems claimed that he heard the story from an old, unnamed neighbor who claimed to have known George Washington when he was a small child. As the only reference to the story, it can hardly be accepted as a credible source. True or not, the story itself does no harm, and as it’s been repeated it so often, it resides deep within the hearts and minds of almost every American. Whatever the role that Mutembo and the other’s played, Zambia was able to achieve its independence without the violence and bloodshed that so many others have had to endure. Surely that is worth any doubt concerning a man who broke a chain to free himself, yet wound up binding the people of Zambia together as a nation.

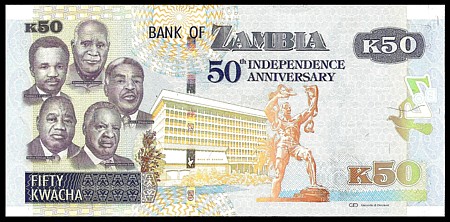

The note below is a 50 Kwacha denomination issued in 2014, the 50th anniversary of Zambian independence. The five portraits are of the five presidents that had held office at the time of issue. Mpundu Mutembo’s Chain Breaker statue is prominent on the reverse.