Chinese Banknotes

A collection of early to mid 19th century banknote designs

There is a wide variety of Chinese banknotes, but one of my favorite designs is the vertical designs which were popular up until the early 20th century. Here is a small collection of notes from various local and provisional banks. As you can see, there is a lot of interesting detail in them, depicting everyday life scenes, flowers, vases, martial arts, waterfalls, etc. Like the themes, their sizes varied considerably. Unfortunately I do not read Chinese, and I’ve had to rely heavily on the information that came with these when I purchased them. I would like to thank Mr. Erwin Beyer, an expert in Chinese banknotes, for his friendly assistance in the translation of words, deciphering changed place names, and helping me to better understand and appreciate these notes. Thanks also goes to Meng Wengeng for the insights into the language, stories and history. To them I say “Thank you very much”!

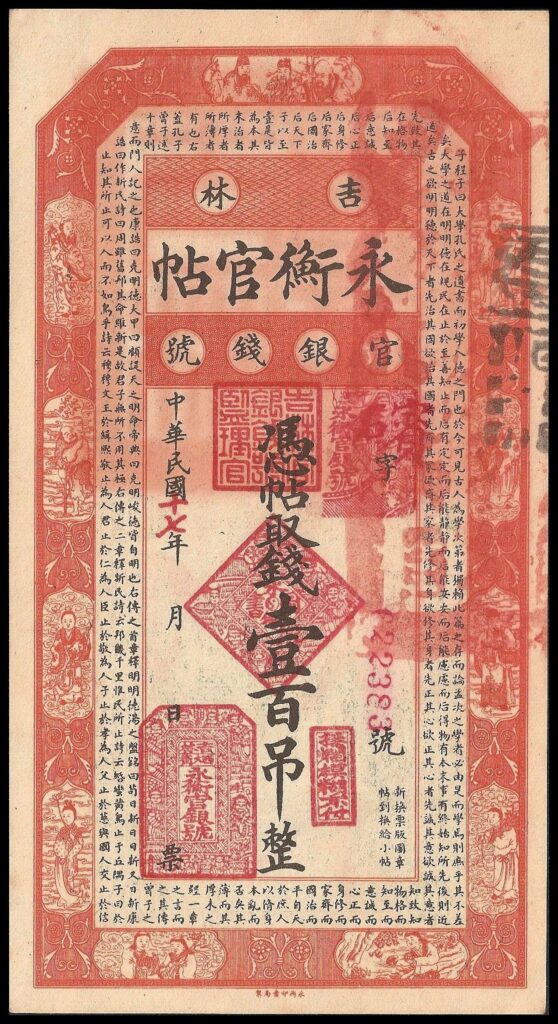

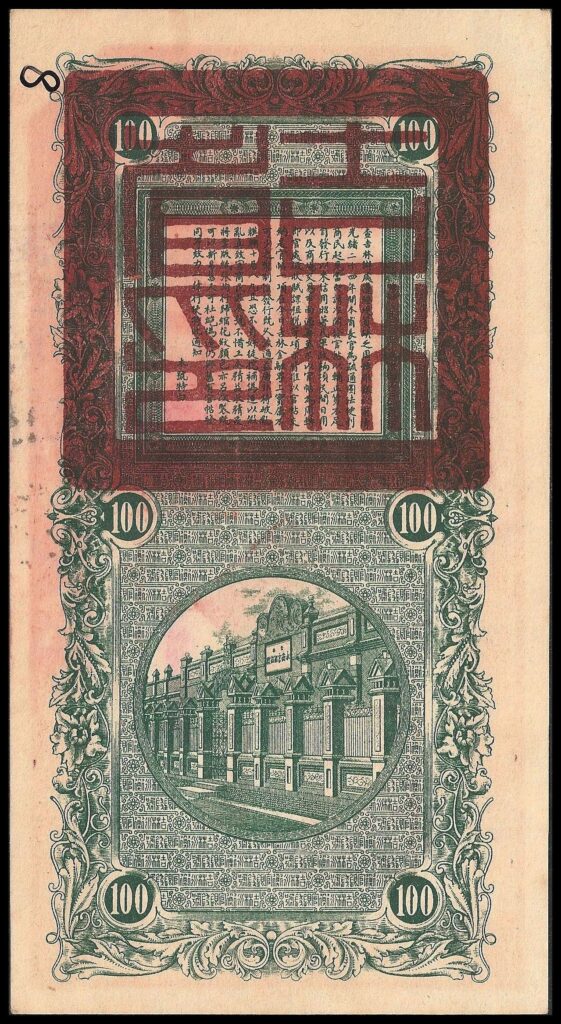

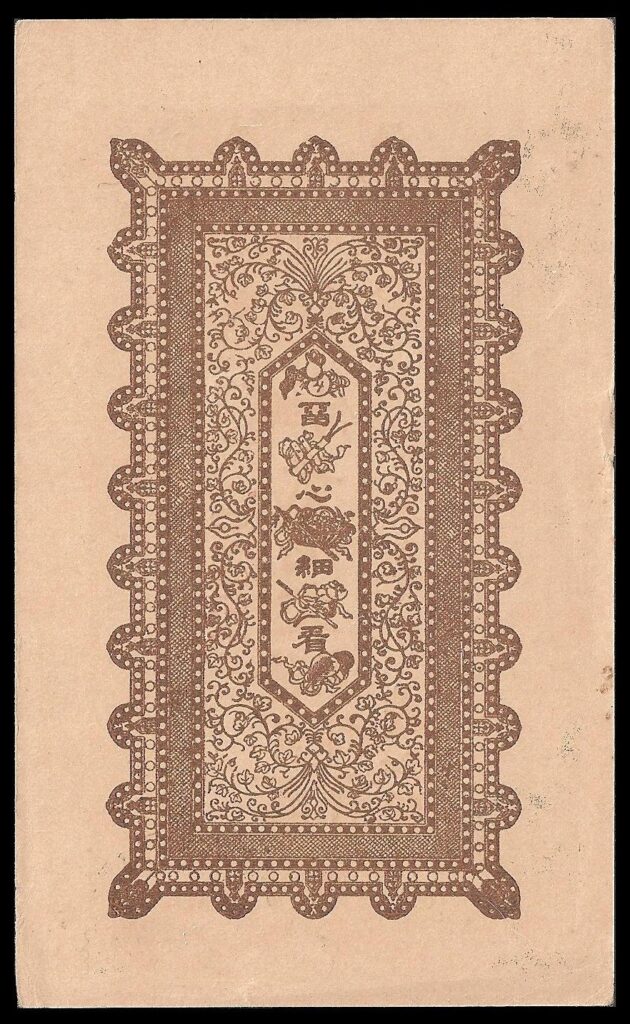

China 100 Tiao Kirin Yung Prov. Bank – 1928

China 100 Tiao Kirin Yung Heng Provincial Bank – 1928. You’ll see many overstamps on these notes, which are seals from banks and authorities that verify the authenticity of the banknote. These seals were anti-counterfeiting measures, as well as endorsements for the note to be accepted in areas both within as well as outside of its issuing authority.

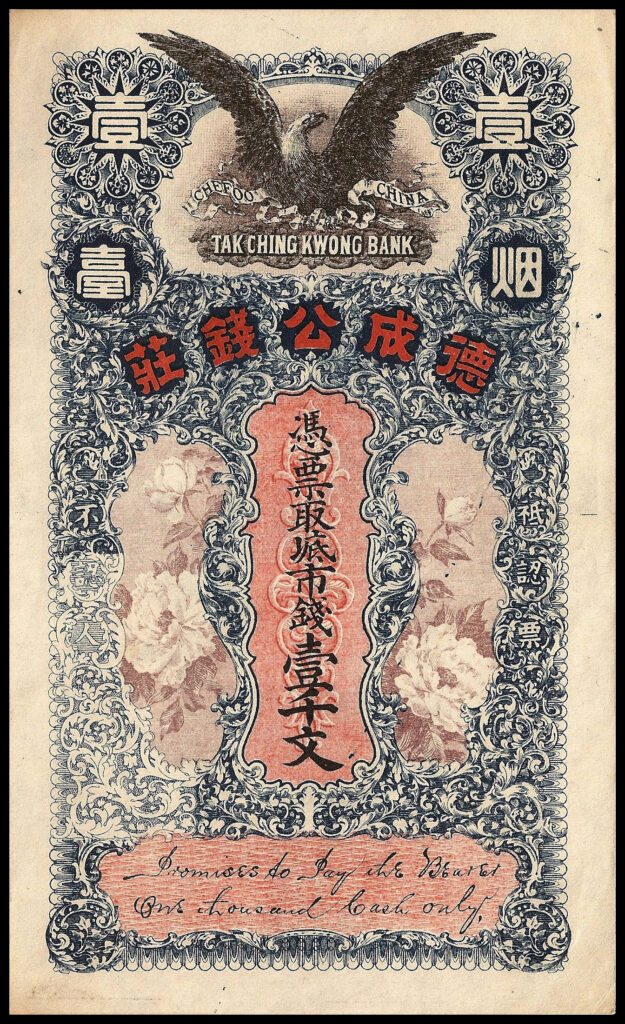

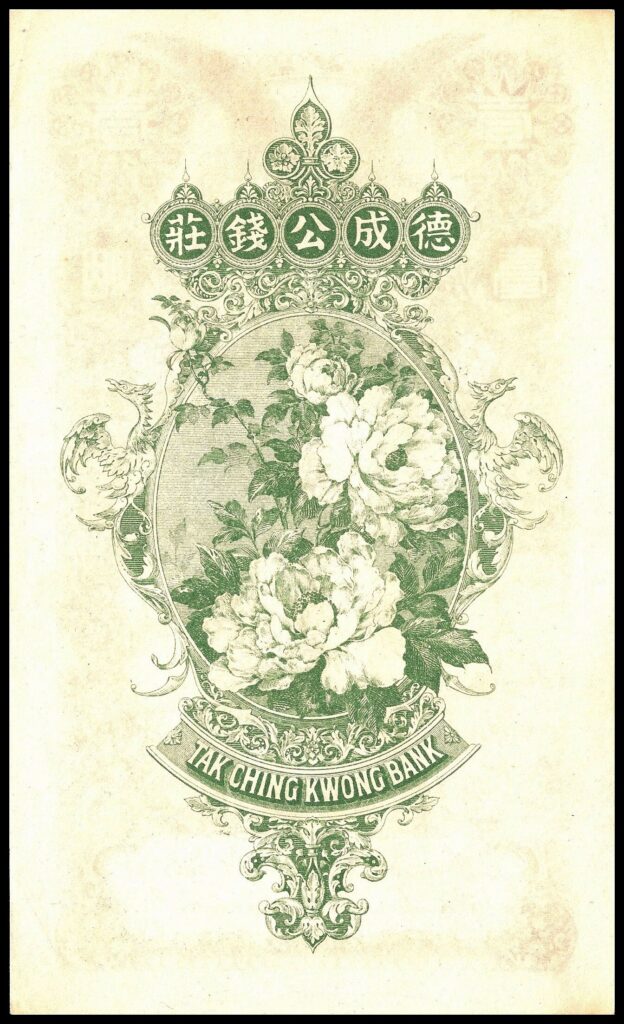

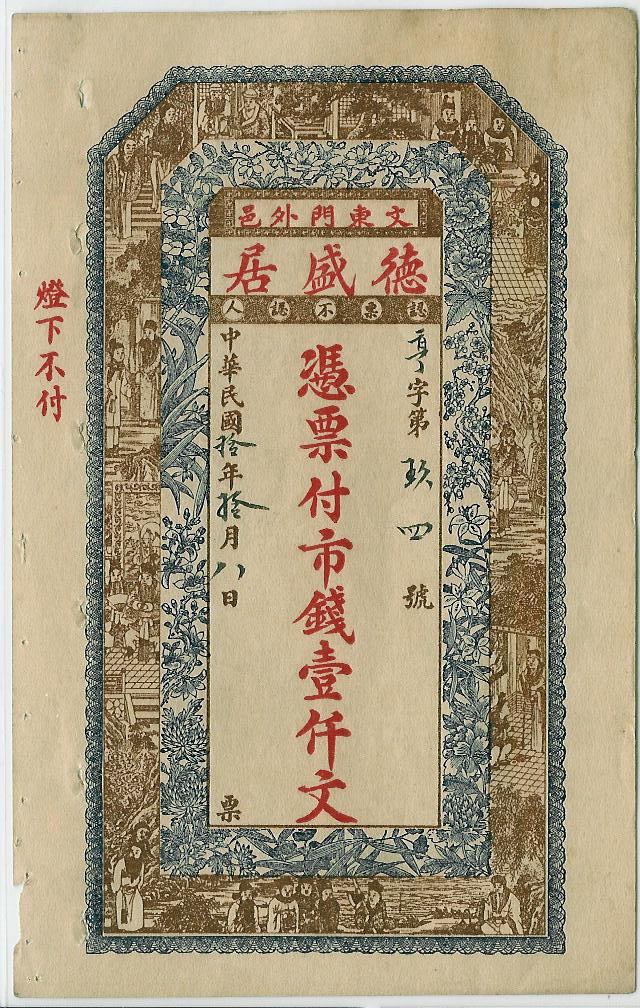

China 1000 Cash – Tak Ching Kwong Bank in Chefoo CHina Shangdong Province 1908-1912

China 1000 Cash – Tak Ching Kwong Bank in Chefoo China – Local Currency from Shangdong Province issued between 1908-1912. This note has no overstamps, but there is a lighter print area to the left. I’ve seen a few of these notes and they all exhibit this same light area and lack of overstamps.

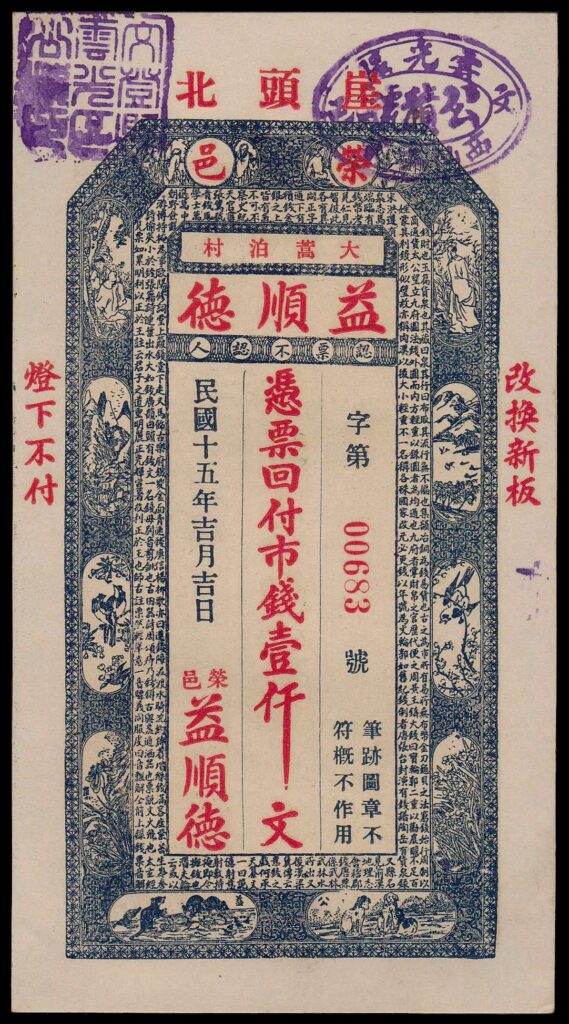

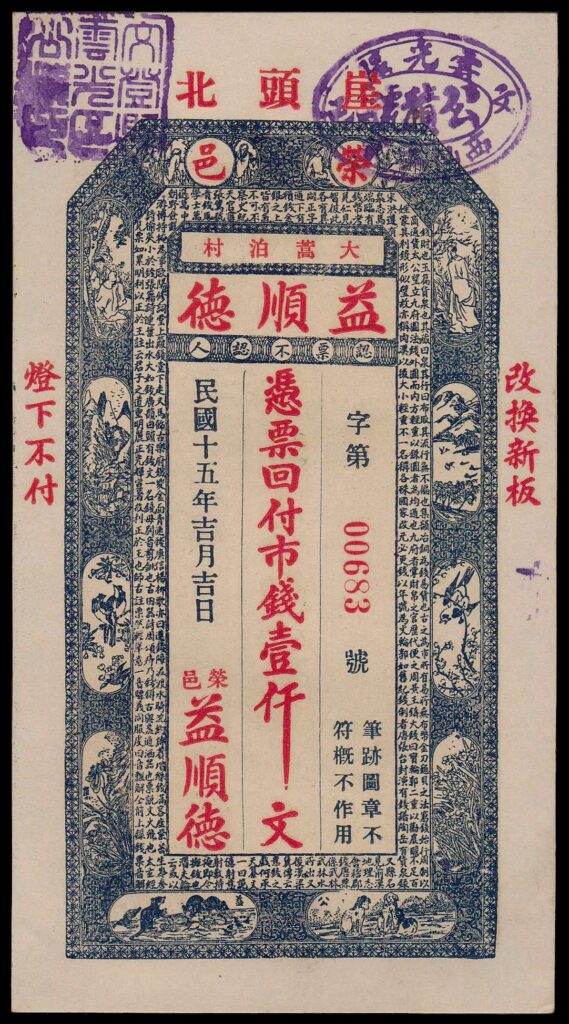

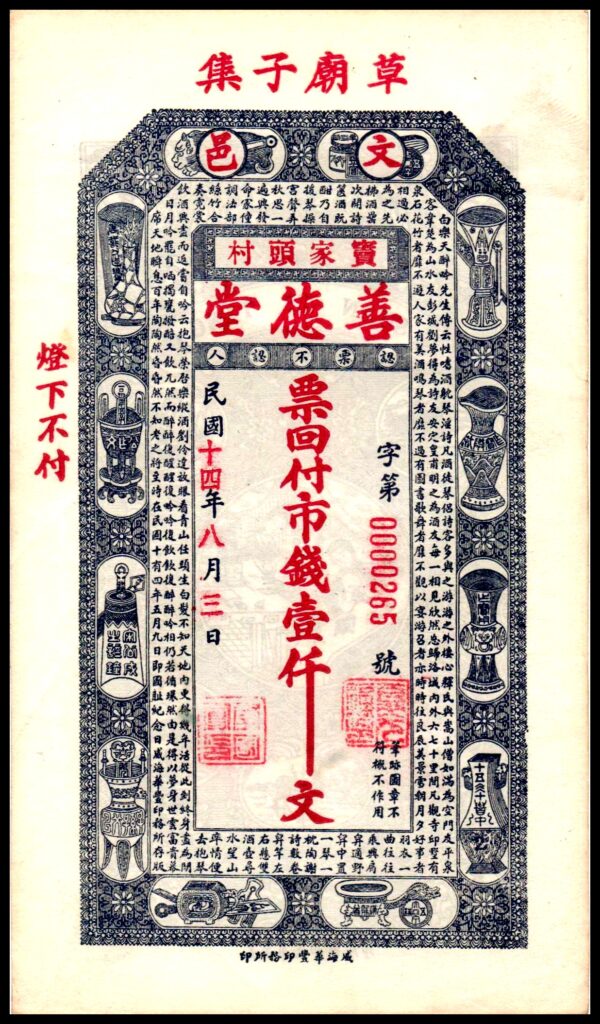

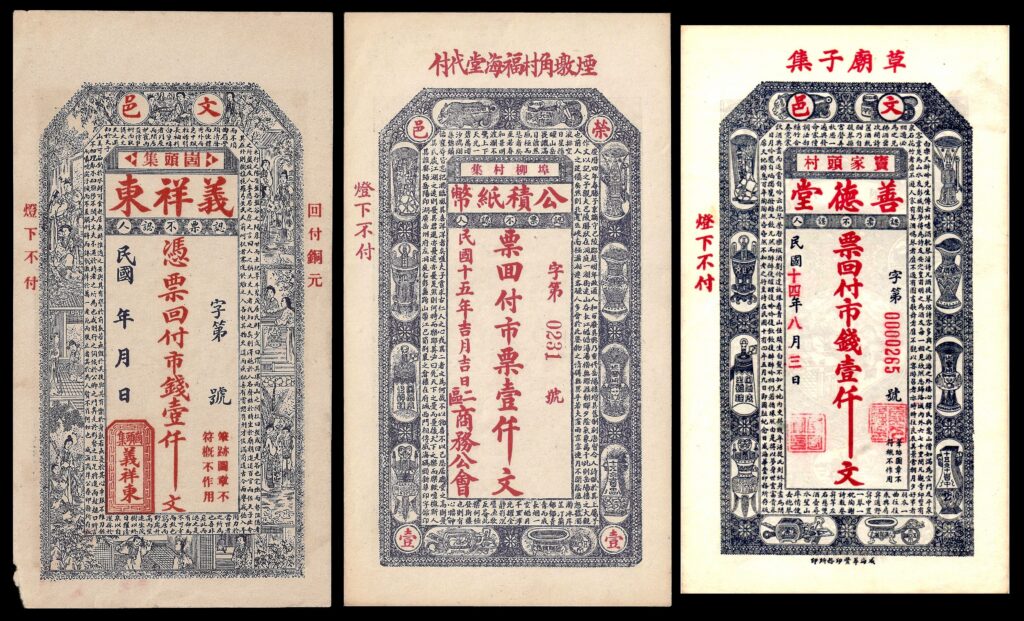

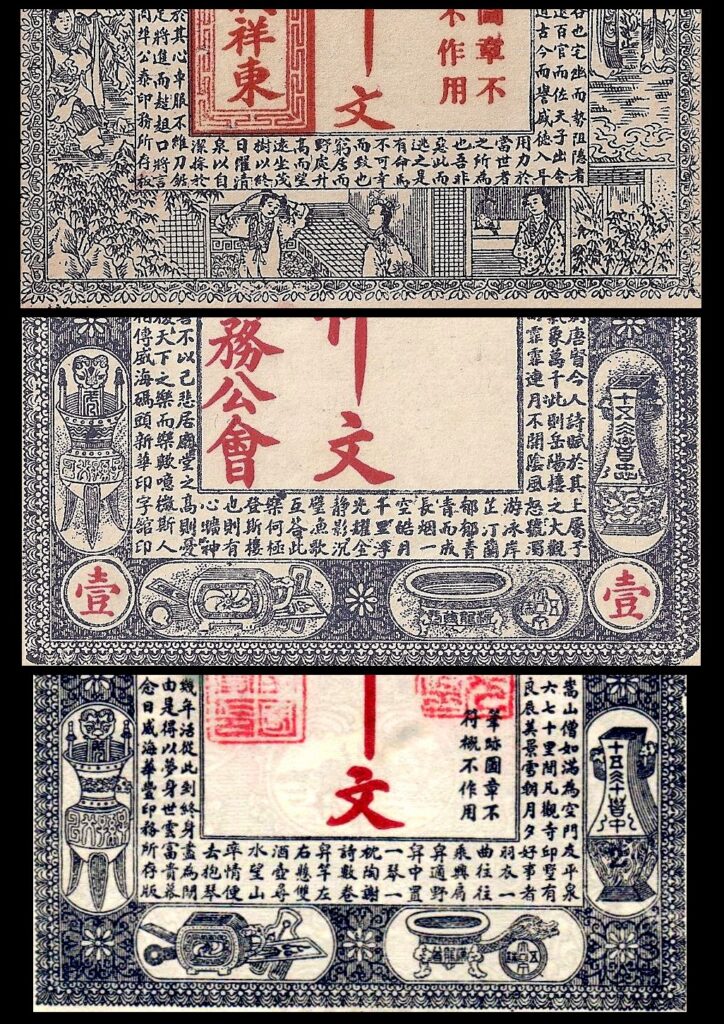

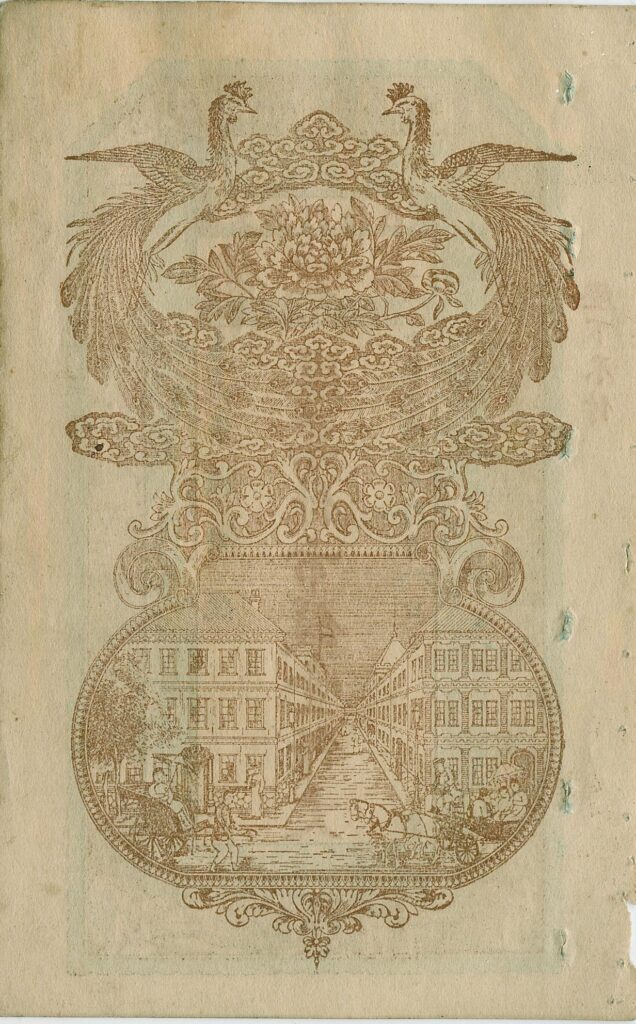

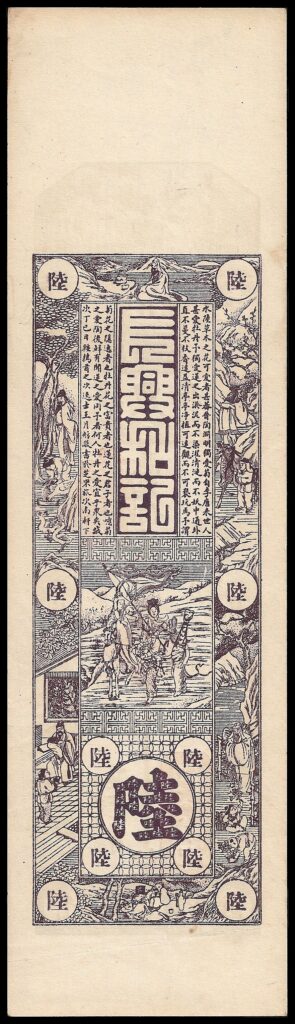

China 1000 Cash Local Note Yu Shueng De

China 1000 Cash dated 1926. This local note is from a company named Yi Shun De, in a city called Rongyi in the Shandong Province. This banknote was printed by Gong Yi, in the city of Weihai in Shangdong Province. The reverse is similar to the note above, showing various martial arts, and are actually vignettes of tales depicting religious and social thoughts as told in operas and legends.

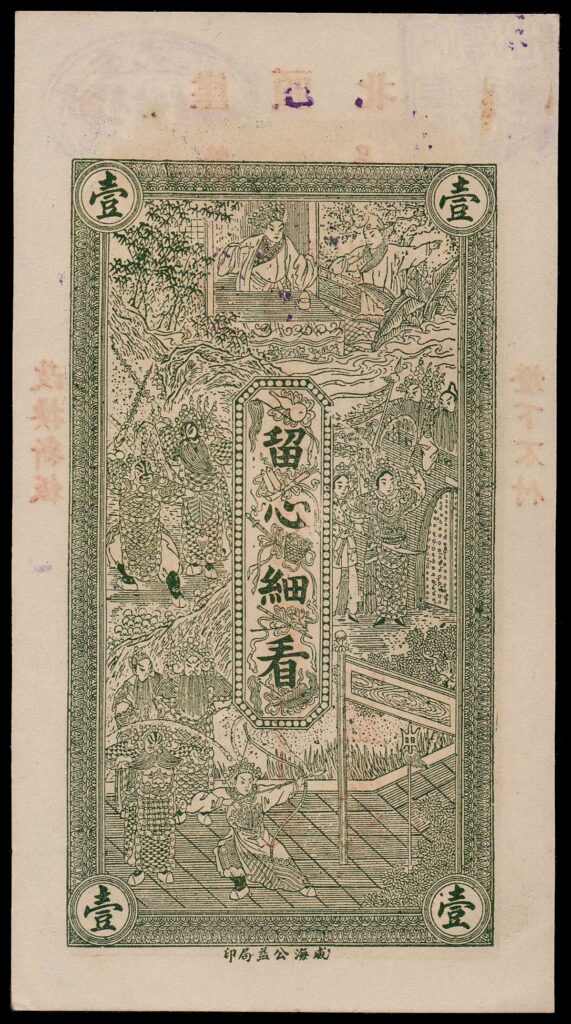

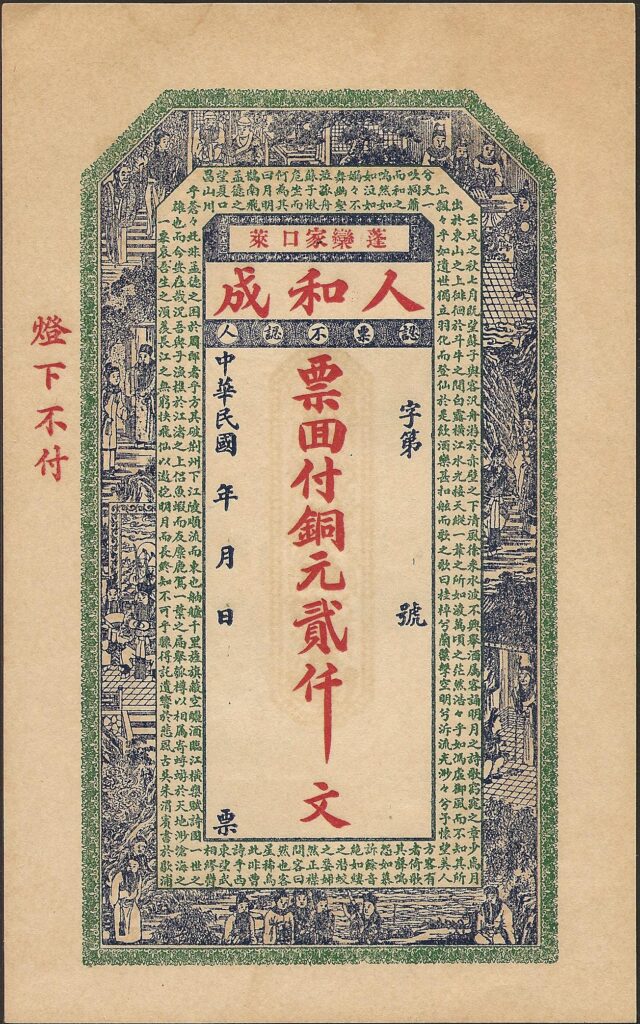

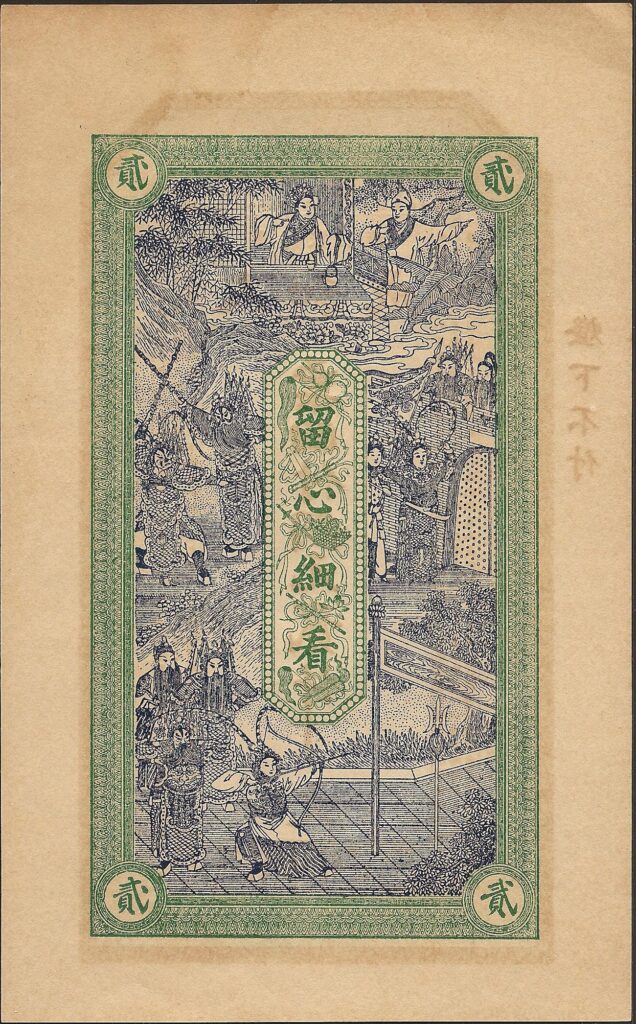

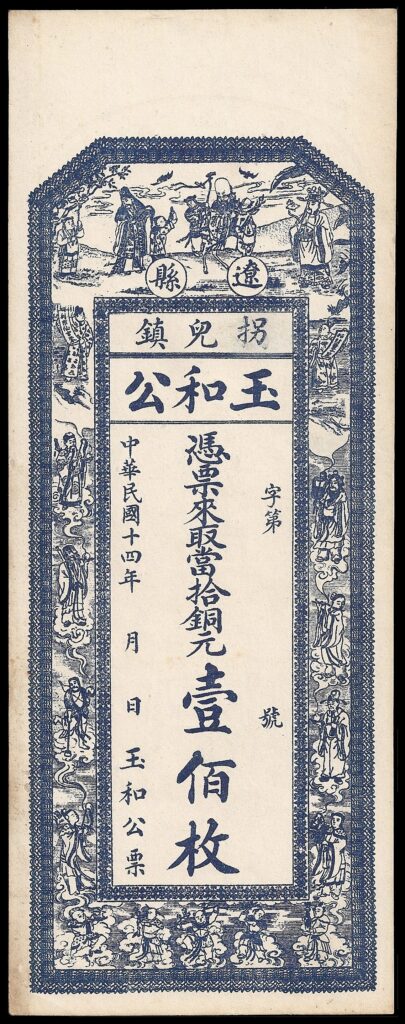

China 2000 Cash Local Note Ren He Cheng

China 2000 Cash undated – Circa 1926. This local note is from a company named Ren He Cheng, within Shandong Province. This banknote is an unissued remainder, so it has no date, printer, issuing company, nor serial number. The reverse is similar to the note above, showing various martial arts, and are actually vignettes of tales depicting religious and social thoughts as told in operas and legends. There are several slight engraving differences between them, likely due to the higher denomination having a greater detail, or the printer/engraver simply being a different artist copying the same basic design. These types of notes were often sold to companies who could order many different designs types from which the printing companies were authorized to sell the private issuers.

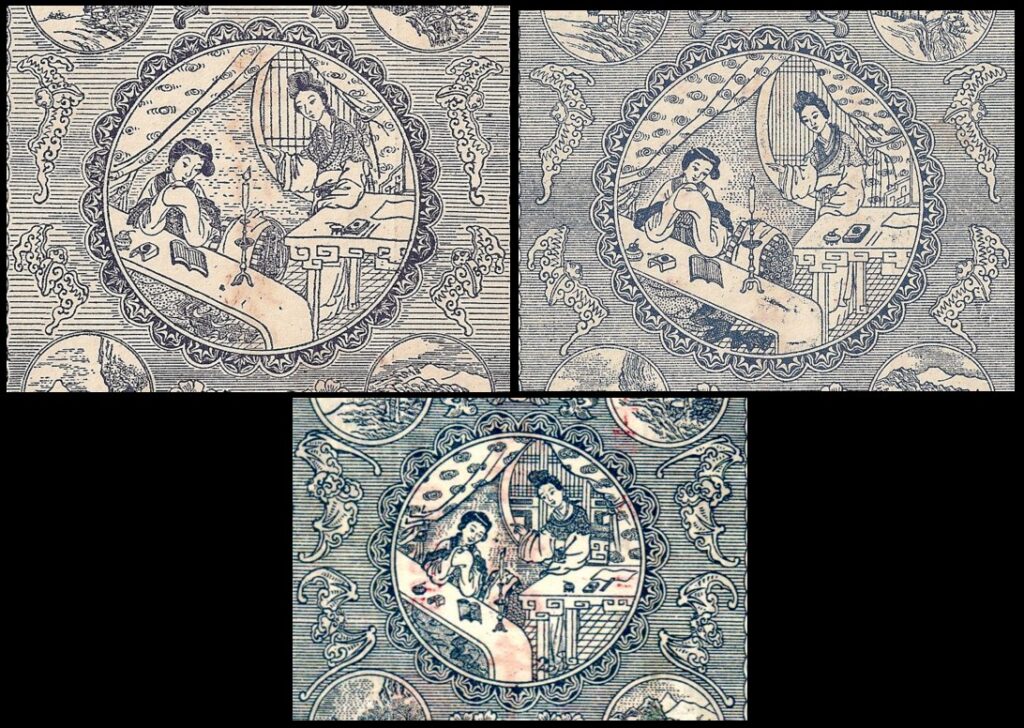

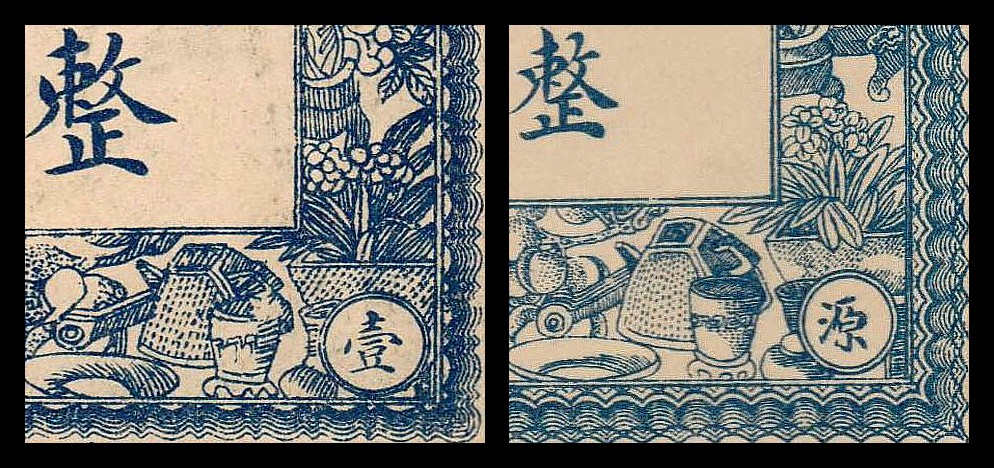

The images on the back of the two notes are almost identical. In these images however, there is more overall detail in the unissued remainder note of a higher denomination than the issued note. While there are many noticeable differences, of particular note are the facial characteristics, the costumes, and the vegetation. See the images below to more easily compare them to each other.

This section below shows the 2000 Cash unissued remainder on top, and the 1000 Cash issued note on the bottom. The top image shows less furrowed brows on the people, a smaller hat on the female, different head tilts, and overall more detail. Note the female’s belt has an extra turn in the top image, and the bottom image lacks the detailed imagery of the table through the teapot handle.

In this image below from the center of these notes, the 2000 Cash is again on top, while the 1000 Cash is on the bottom. There is again more detail in the top note, but note the basket in the center panel, which shows a distinctly different artistic style. A similar discrepancy exists when examining the top right man’s sleeve seen through the opening in the top of the castle wall, and comparing that to the bottom note, where it looks as if the sleeve is protruding in front of the castle. The feet of the men on the left are also not matching up evenly in both images in respect to the women on the right. Other smaller discrepancies are present.

In the following scene, note the tassel on the upright spear, which seems to have a slight wind on the bottom note. The angle on the turn in the path is different, and the details overall show quite a notable difference in the costumes. Compare the design of the archer’s hat and gown, the differences in the face on the chest-plate of the man behind the archer, and wood crosspiece over the spear.

As mentioned before, these vignettes are of tales depicting religious and social thoughts as told in operas and legends. Thanks to Meng Wengeng from China, who told me the titles of these scenes. Here’s a brief description:

“The Butterfly Lovers”

“The Butterfly Lovers” is a Chinese legend of the tragic love between two lovers, Liang Shanbo and Zhu Yingtai. The opera takes place during the Eastern Jin Dynasty (AD 317-420), when women were discouraged from scholarly pursuits. Zhu , the daughter of a wealthy family in Zhejiang, convinces her father to allow her to attend classes, but must do so disguised as a man. During her journey to Hangzhou, she has an encounter with the scholar, Liang, and Zhu gradually falls in love with Liang.

“Mu Guiying Takes Command”

A well-known female general during the Song Dynasty (AD 960 – 1126), Mu Guiying learned martial arts at a young age from her bandit father who ruled the Muke Fortress.

One day Yang Zongbao, a young warrior of the Yang clan, paid her a visit. Yang Zongbao was serving in the Song army under his father’s command. They needed to learn how to defeat the Liao army’s defenses, and it was rumored that Mu Guiying knew the secret.

Mu at first refused, but as she was smitten with Yang, she consented to divulge the secret if Yang fought a duel with her. If she lost, Mu would reveal the secret. If she won, Yang must marry her. She won, and after a quick marriage, Yang had to report back to his father’s army, defeated and married to the one who defeated him.

Yang’s father ordered his disgraced son executed. To save her husband, Mu came out of the fortress and engaged in a battle with Yang’s father also defeating him. Finally Yang’s father agreed to the marriage and welcomed Mu to his family and troops, where she revealed the secret maneuvers, and the Song army defeated the Liao army. Mu would rise in rank and eventually lead the army.

“Romance of the Three Kingdoms”

The Romance of the Three Kingdoms describes a history of a hundred years from the end of the Eastern Han Dynasty to the beginning of the Western Jin Dynasty, reflecting upon the political and military struggles during the Three Kingdoms era and changes in society. It implies the people’s hope for the revival of the Han Dynasty and the orthodox thoughts of the royal family. The tales of the Three Kingdoms are not simple.

“Water Margin – Outlaws of the Marsh”

Based upon the real-life bandit Song Jiang and his companions, this Chinese equivalent of the English classic Robin Hood and His Merry Men is a tale of peasant uprising in the twelfth century. It is called Water Margin because the bandits use the Liangshan Mountain on the margin of a huge watery marsh as their base camp. Within this story is the tale below:

“Water Margin: Three Strikes on Zhujiazhuang” (Vignette of attacking the city gate)

A tale about the conflict between Liangshan Rebels and the Zhujiazhuang Army. Zhujiazhuang and the landlords of the three manor houses of Hujiazhuang and Lijiazhuang formed a pact to work together and catch the thieves in Liangshanbo who have been creating problems. “Three Strikes on Zhujiazhuang” is the storyline in the classical novel “Water Margin” and is considered to be the most exciting story in “Water Margin”. This story focuses on describing events and contradictions, describing strategies, tactics, and methods to resolve contradictions, and fully embodies the dialectical thinking, the ability to view issues from multiple perspectives and arrive at the most best method of seemingly contradictory information.

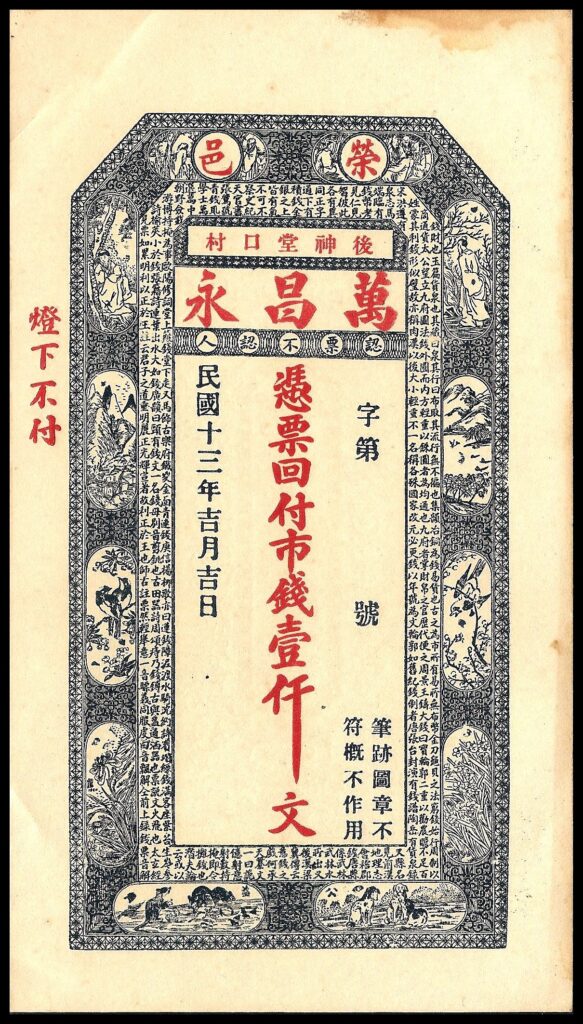

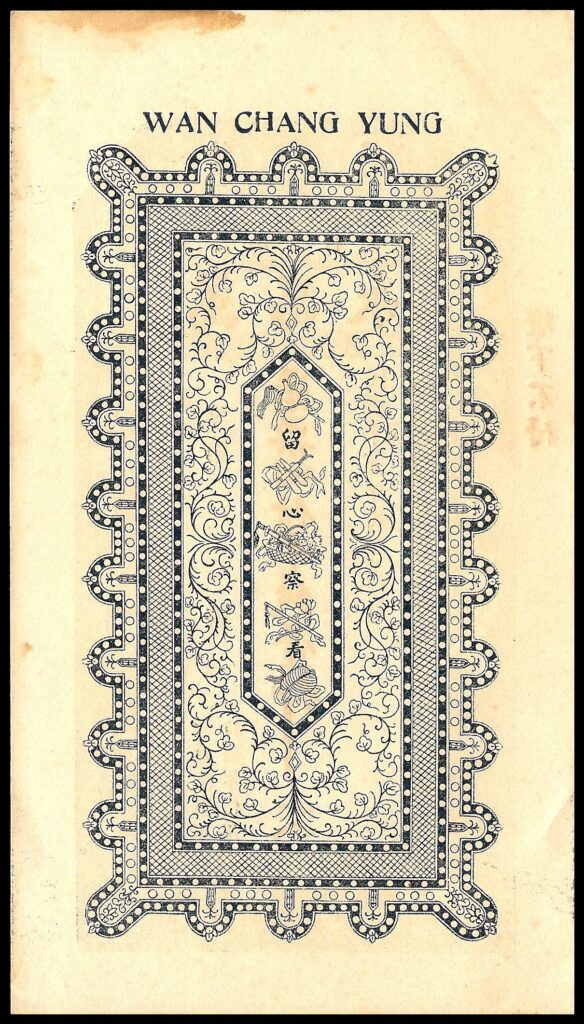

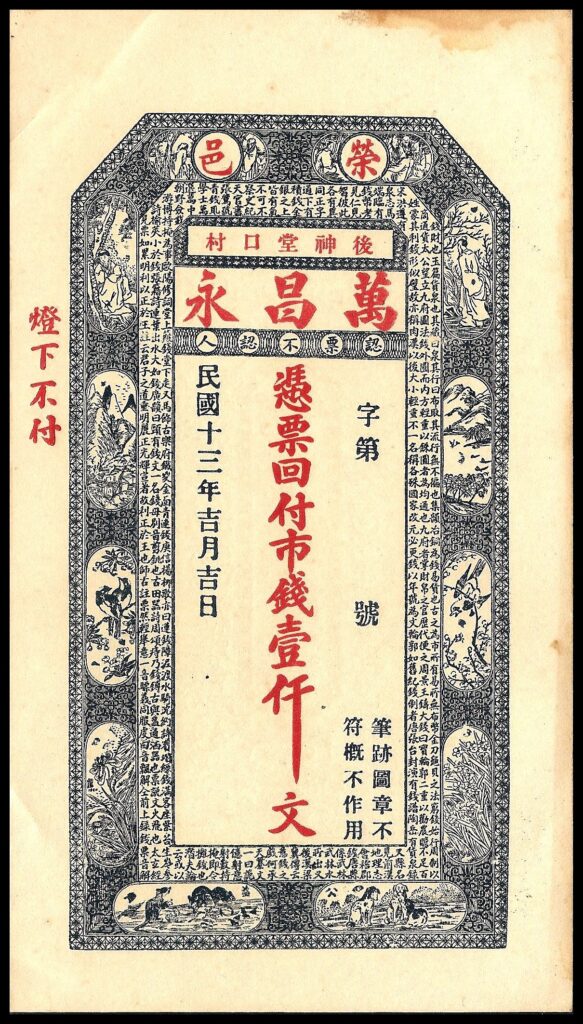

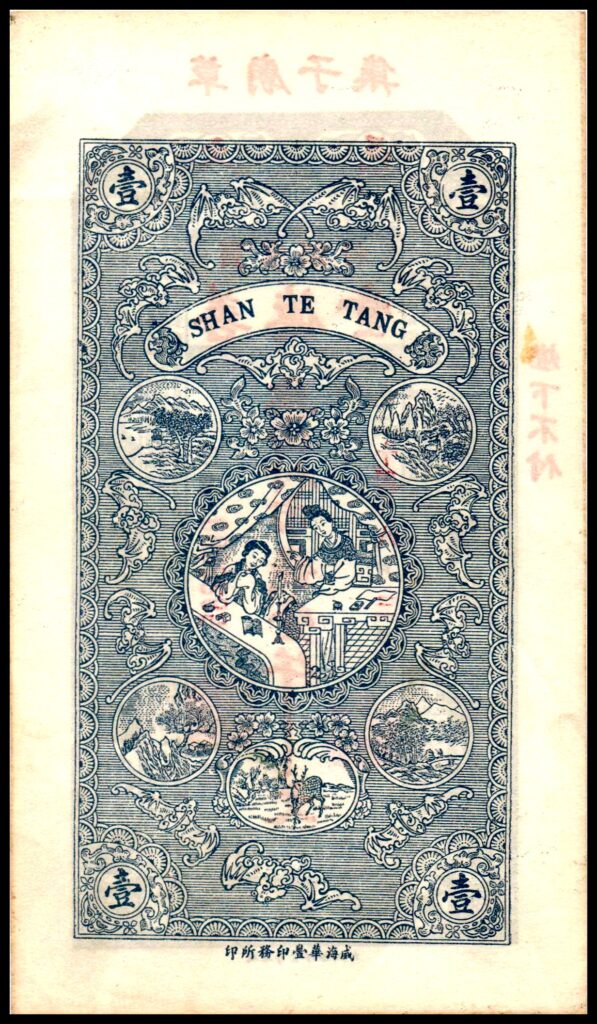

China 1000 Cash Local Note Wan Chang Yung – 1924

This local banknote is also a remainder – unissued – note. Notice that the front of this note is similar to the 1000 cash from the above referenced Yu Shueng De issuer. The reverse is different with Wan Chang Yung printed on the top in English. The notes use of the same image on the front goes to show that the images were recycled for use. This recycling no doubtedly came in handy when an issuer who was less trustworthy tried to emulate a more trusted issuer.

The back of this note should be compared with another note below, the China Shanghai Yi He Hao 200 Cash – 1932. While it is an obvious copy of the same design, it is also obviously differs in scale and some styling.

Recycling images and motifs isn’t something that the Chinese were alone with. There are several examples of vignettes being reused in notes printed by large printer companies in North and South America using portions of vignettes on notes for different countries, well into the early 1900s, just like this Chinese banknote. During the time that these were printed, China effectively was without a true central government, and printing companies were numerous and often even just a small shop. I’ve been informed that between 1949 and 1976, a most of the printers carved blocks and other items were destroyed or thrown away, leaving a void in historical knowledge of their printing practices.

The reverse of this note has both Western text. Though I cannot be certain with this note, these words are often meaningless, as notes were sometimes given a western ‘flavor’. Perhaps they were placed there in an effort to give the appearance of western companies backing of the notes, thus making them accepted among the local inhabitants who thought they were more secure than a typical local issue. Of course it is possible that this was a true romanization of the issuer name, though given the reused front image, I remain skeptical.

China 1000 Cash Local Note comparison – 1920’s

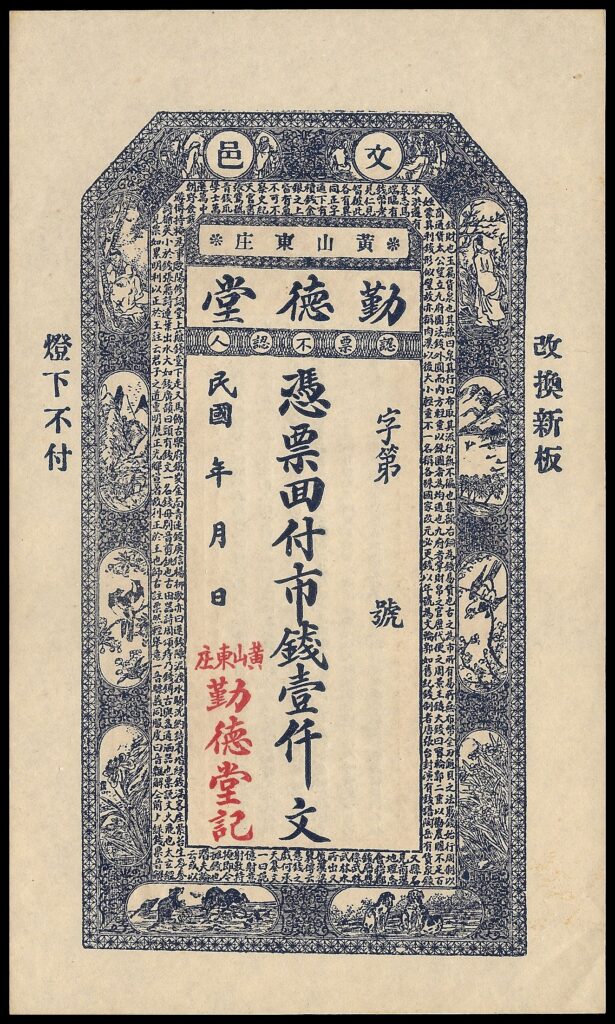

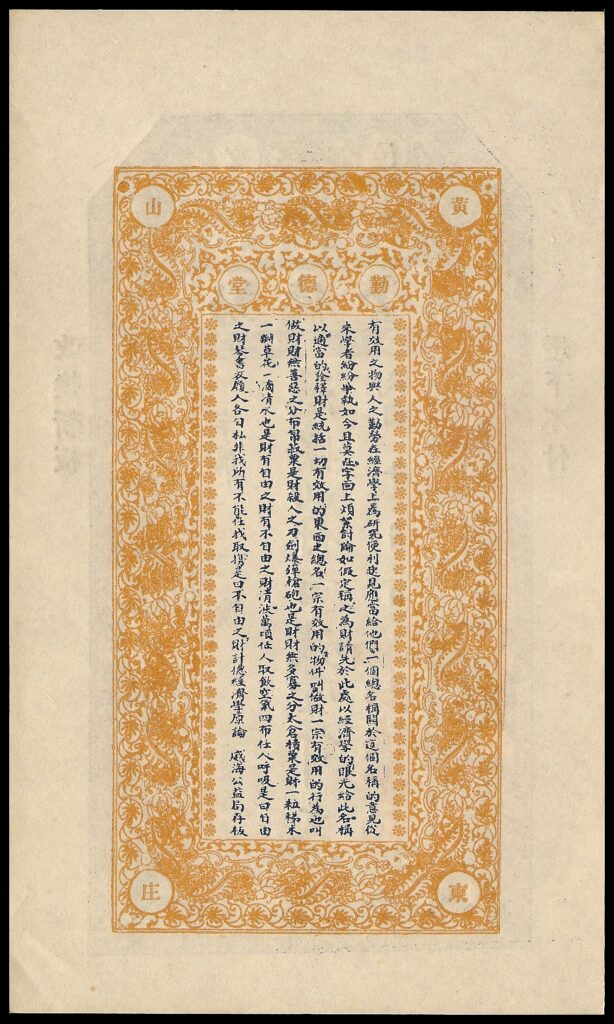

The following local banknote is also a remainder – unissued – note with no date, and an unusual name of “:Don Deloitte” (online translators!?). Notice that the front of this note is similar to the 1000 cash from the above referenced Yu Shueng De of 1926 and the Wan Chang Yung of 1924.

These notes with duplicated imagery further illustrate that the reuse of designs was in practice. Many aspects of the notes front design and text are similar, but there are some differences.

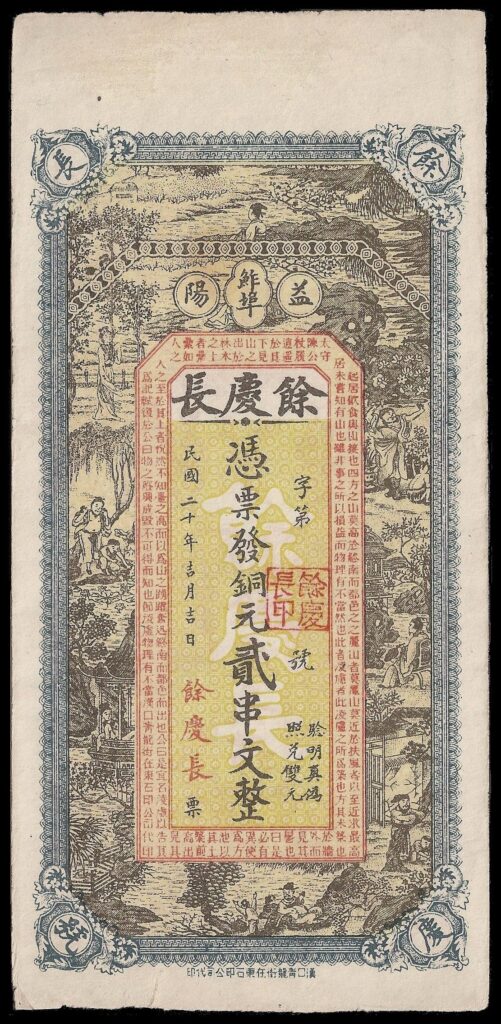

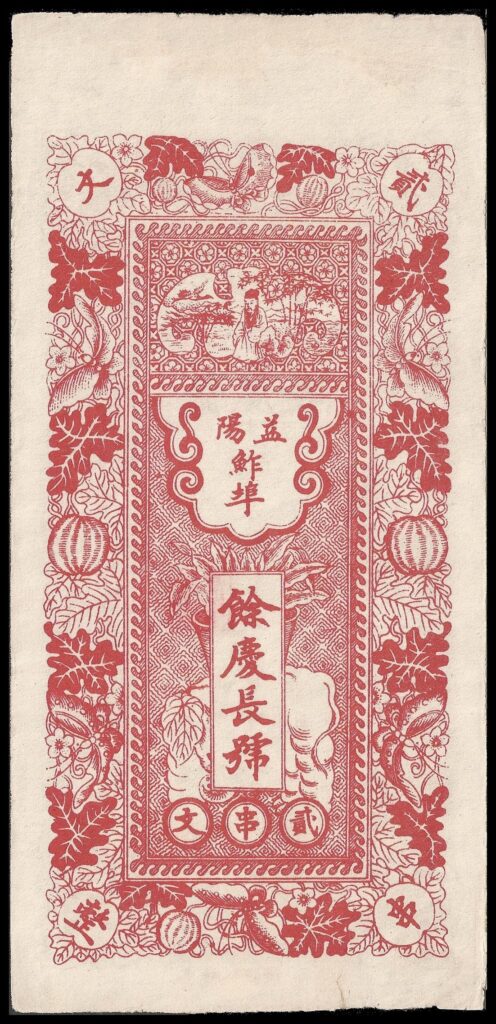

China Hunan Provence Yi Ching Chan Bank 2 String – 1931

China Hunan Province Yi Ching Chan Bank 2 String – 1931. The front shows scenes from everyday life, while the back has a man at top with what looks to be an elephant behind a seal. This note was issued in the city of Bengbu in northern Anhui Province.

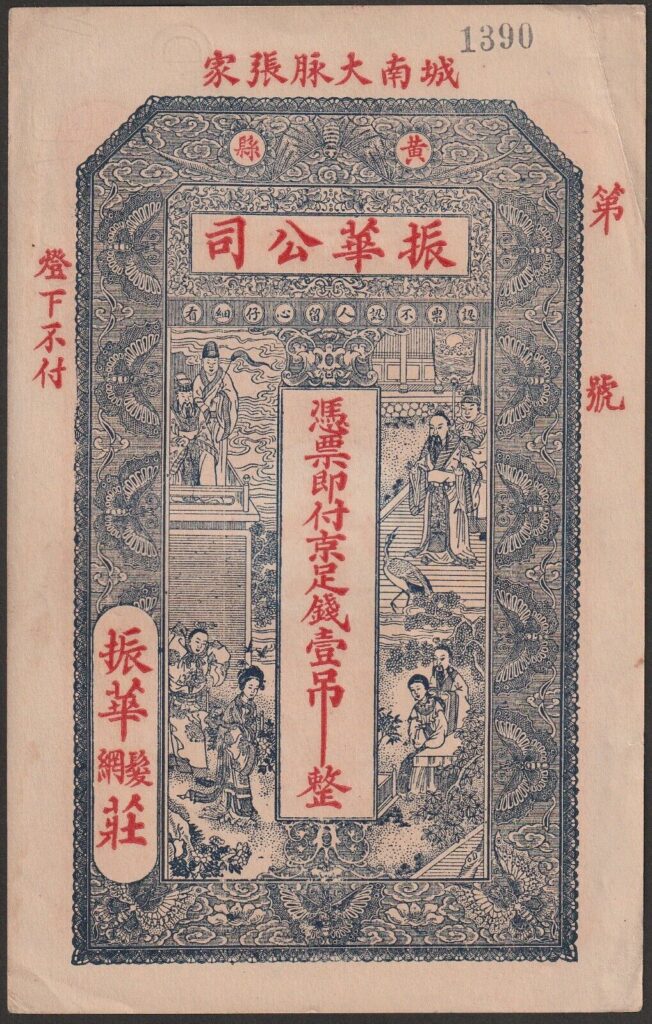

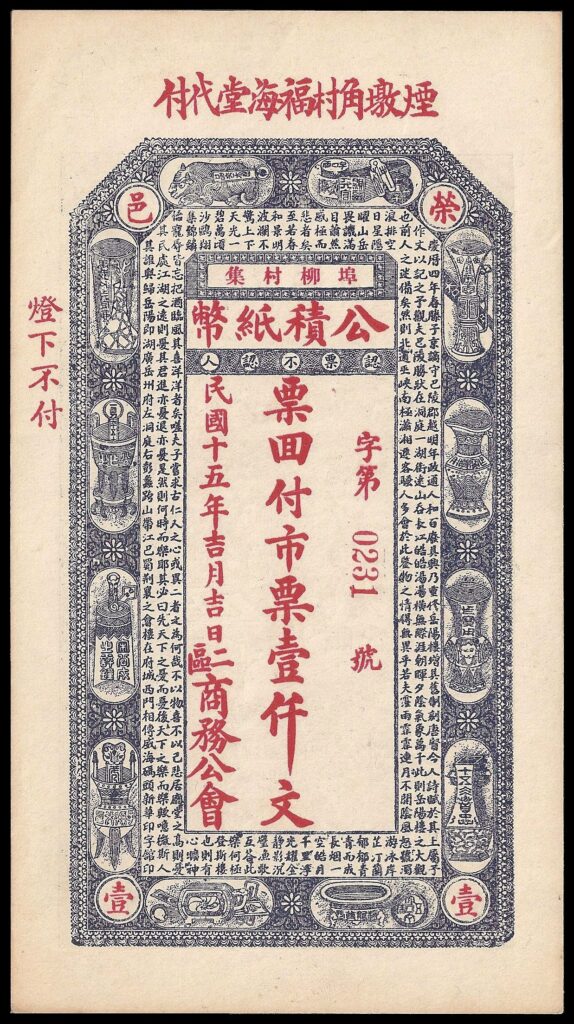

China Local Note Zhangmai Da Nancheng 1 String – Circa 1920’s printed by Huangzeng Company for Zenhua village

China 1 String – is from the 1920’s – 1930’s, and is a remainder with no serial number. Oddly this has a stamp at top of 1390 which most likely has nothing to do with the official printing nor was intended for possible use. Names were translated via Google Photo Translate adn leave me in quite a lot of doubt as to the accuracy.

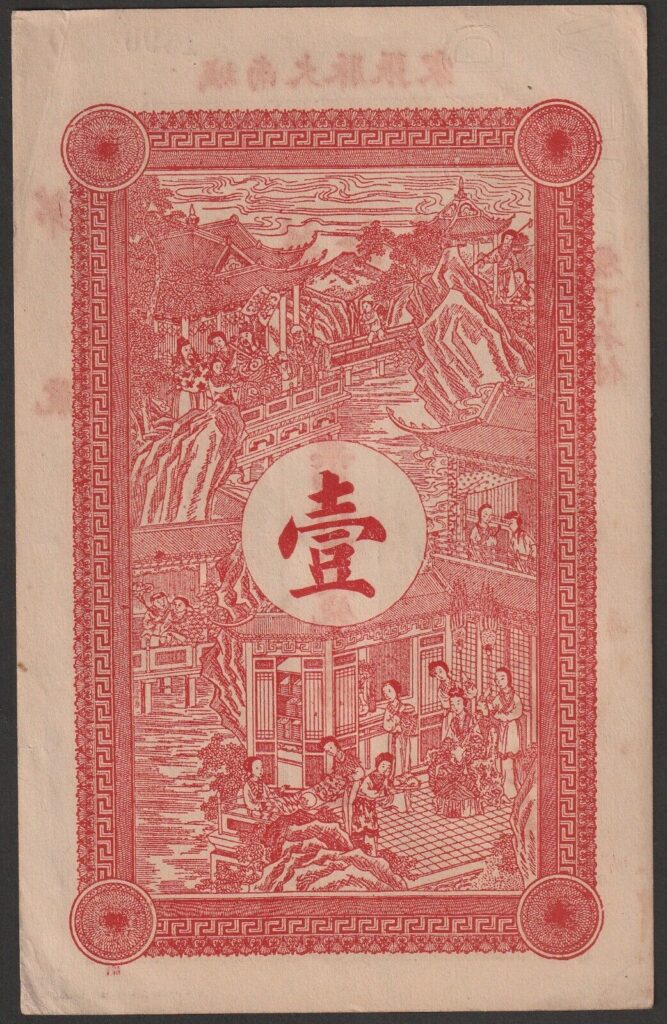

The front has a stylized bat on top and is surrounded by butterflies. The center shows four scenes with two people each, one with a peacock. The back is in red with a prominent character for the number 1 at center, and various household scenes taking place alongside a river.

But perhaps the most striking item is it’s watermark.

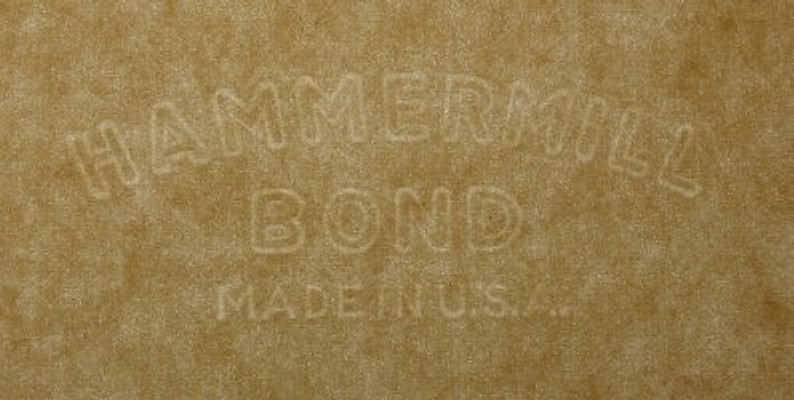

which though not atypical, is surprising for me to see on these type of notes. A closer look showed western (English) letters were used for the watermark. It is obscured by the printed images on front and back, and cut off by the edge, but what I first thought might be a German name eventually was deduced to be Hammermill Bond, a well-known paper mill in the USA.

Hammermill has been in business since 1899, and while it may not be surprising that their paper was watermarked and in use in the 1920’s-1930’s when this note was likely printed, it nevertheless surprises me that a Chinese company would print a banknote on paper imported from the USA. Of course the idea of it being a counterfeit came to mind, but as a contemporary counterfeit, it was a small sum on a local note which would not be a great profit for most endeavors, and for a modern counterfeit, it is too vague of a collectible to be of any profit at all – well, at least not from my non-criminal point of view. The printing is rudimentary as is typical of the time for these style of notes, but nothing struck out at me as a counterfeit.

While I’m sure that there will never be an answer as to why a Chinese Private Currency Banknote would use paper made outside of China in the early 20th century, I thought it may be worthwhile to post here and see if there is anyone else who has found instance of a similar occurrence, and to put it in this electronic form for others to perhaps reference in the future.

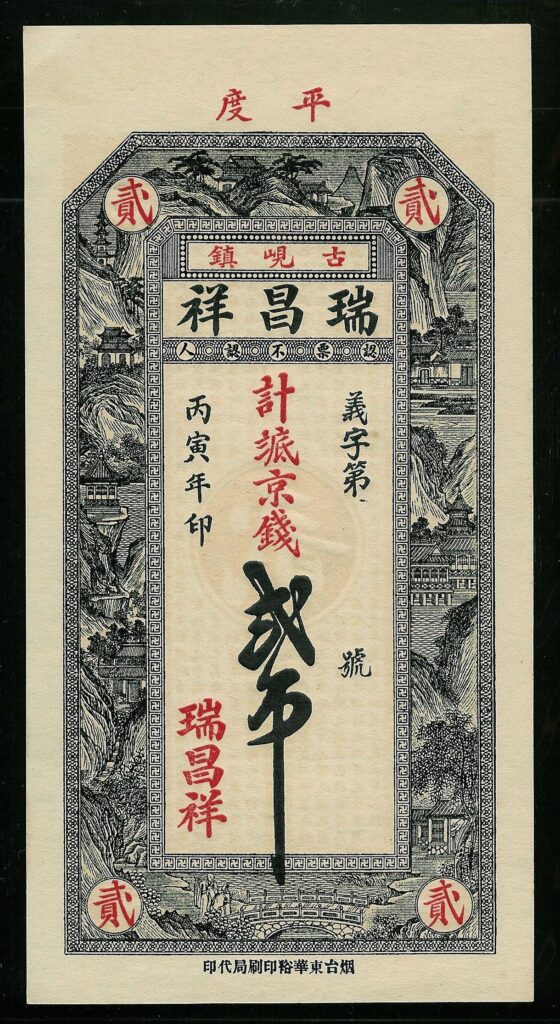

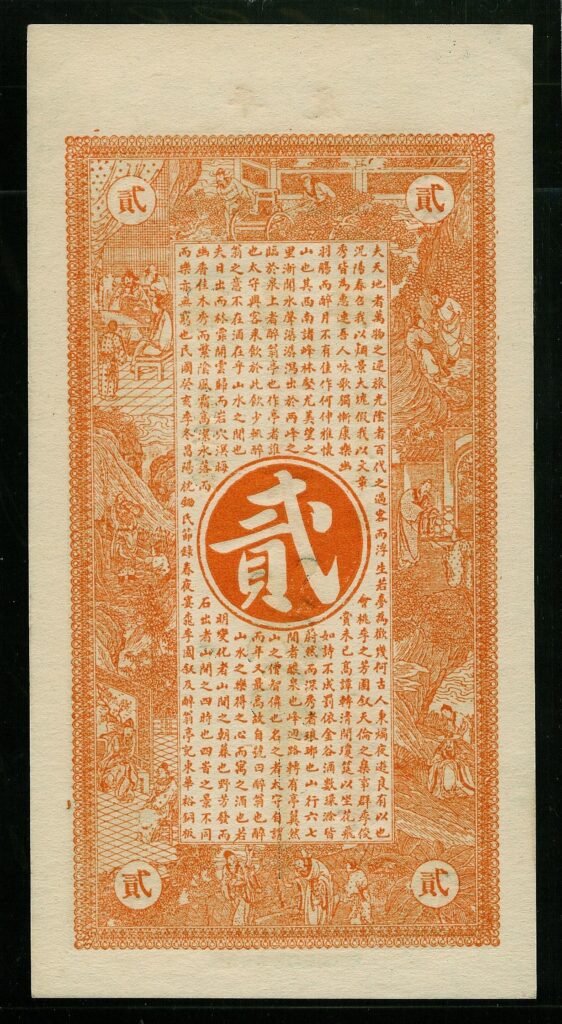

China Local Note Shangtung, Pingdu, Shui Chang Xiang 2 Tiao – 1926

China Local Note Shangtung, Pingdu, Shui Chang Xiang 2 Tiao – 1926. Mountain scenes at front with depictions of everyday life on the back.

China 1000 Cash local banknote – 1921

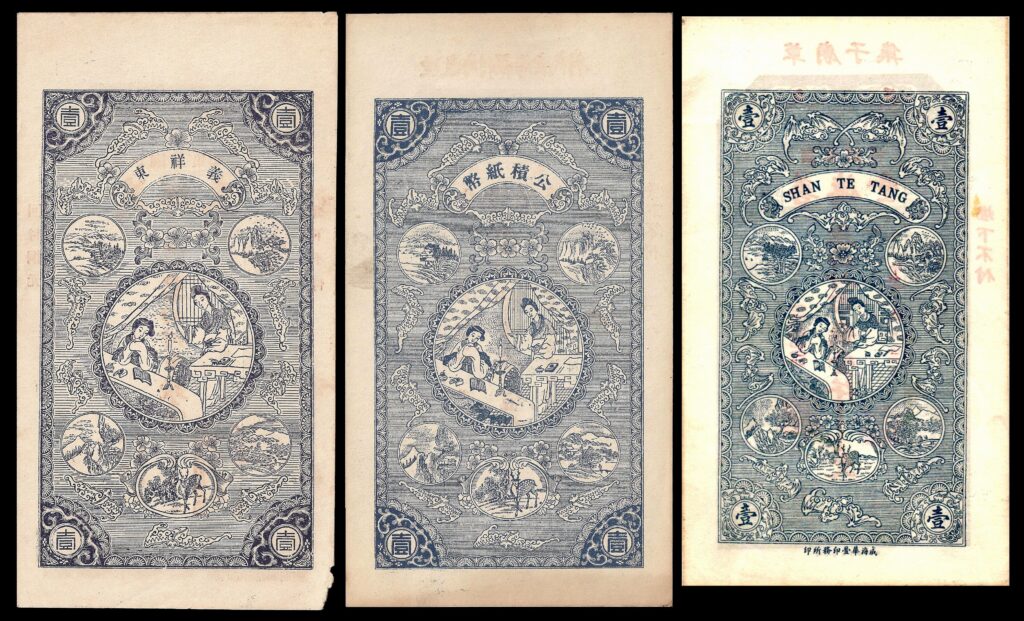

The reverse of this note is the same design as the two following notes. There are some inking thickness variations and text in the crescent at top is different. The printers at the time would sell designs to local banks and print them per their specifications. This one evidently was one variation of a different bank or branch. The plates that were used to make notes at this time were generally metal but some were still made from wood cut blocks. The basic design was kept, but another artist might be making the new printing plate, and certain details could be changed. Compare the flame on the candle, ink splotches on the tablecloth, shading behind the lady in center, position of the second lady’s pointing hand. Background lines are all quite different, as are certain details with the stylized flying bats, the tables, and the gates.

China Shanghai Kong Ji Bank 1000 Cash – 1926

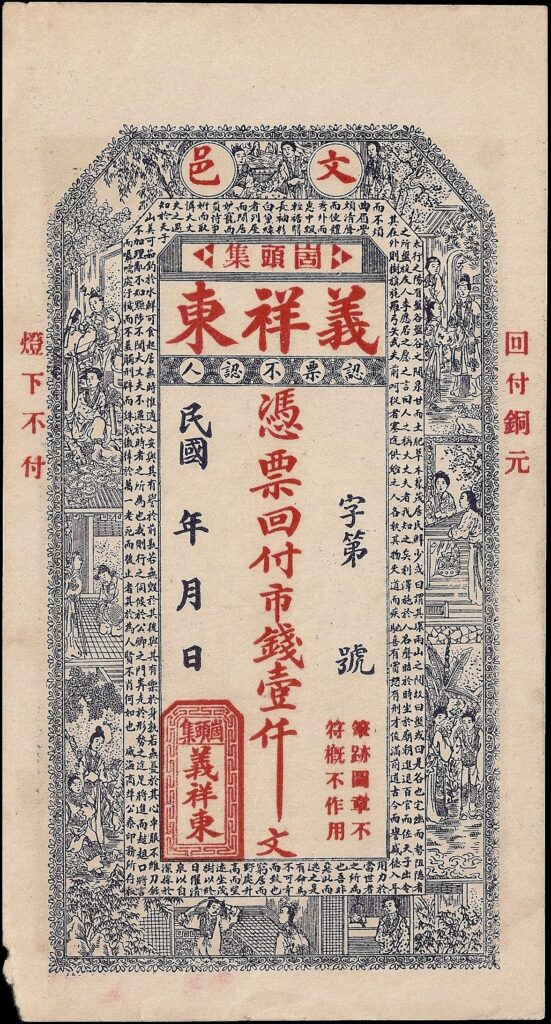

China 1000 Cash dated 1926. This note was issued by a company called Yi Xiang Dong in the city of Wenyi, now called Wendeng, in Shandong province. The text area at the lower right where the date should be is incomplete which means it is a remainder (an unissued note). The date begins with “Min Guo…” which means that the note was issued in Republican times (after 1911).

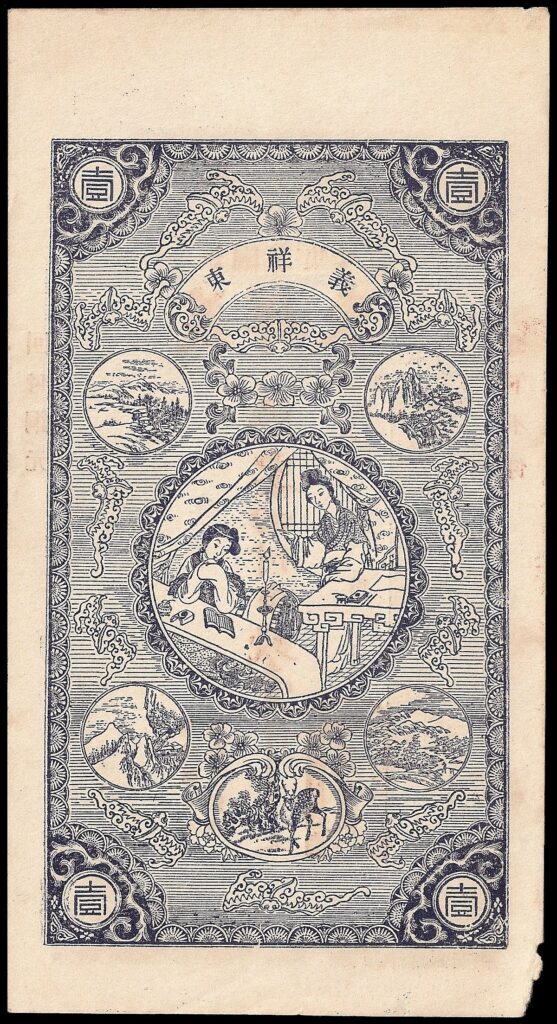

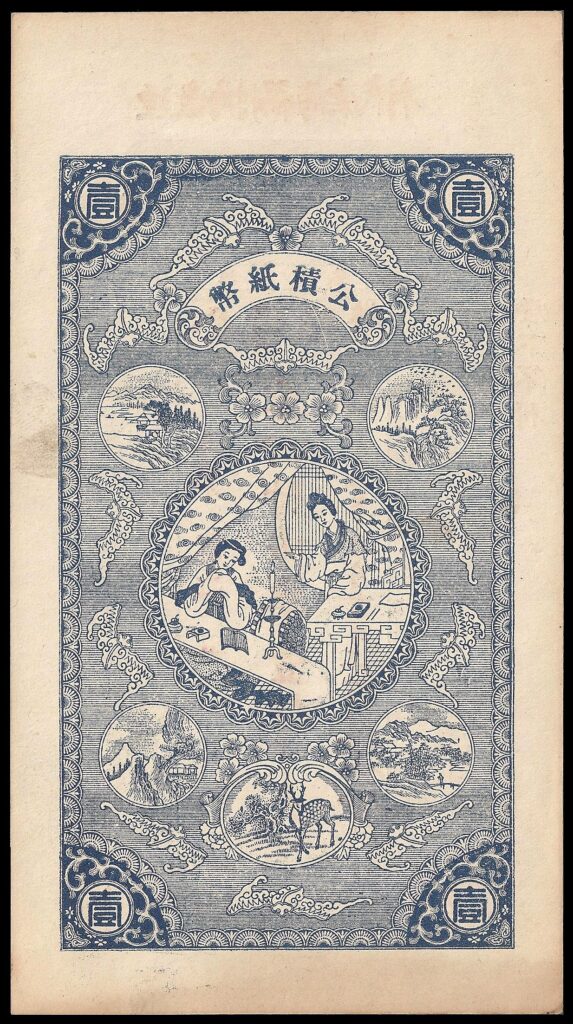

China Shanghai Shan Te Tang 1000 Cash – 1925

China 1000 Cash dated 1925. This note was issued by a company called Shan Te Tang, as written in English on the reverse. This note was an issued example, complete with date and serial numbers. In examining this note, you can see that there is an oddity in the drawings. While similar, on the reverse, there is a western number 2 in the table leg on the central vignette – which is not only missing on the other notes, but the leg is not obscurred as it is in the other notes. In addition, there is a western number 2 on the bottom right vase that is not shown on the note above.

In considering whether some, or all, of these notes may be counterfeit, I am at a loss. It is certainly possible, but the printing techniques used at the time, along with the inaccessible history of detailed records from these companies, makes it impossible to say for certain. Each of the notes has its own merits and problems which lead me in a circle each time. Perhaps it is a bit naive, but until I have more information, I will accept the offered idea of them being issued by various companies and the carved images being made by different artists within those companies.

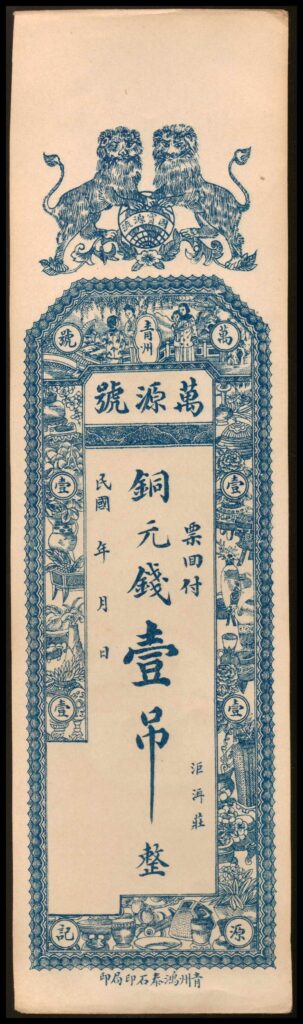

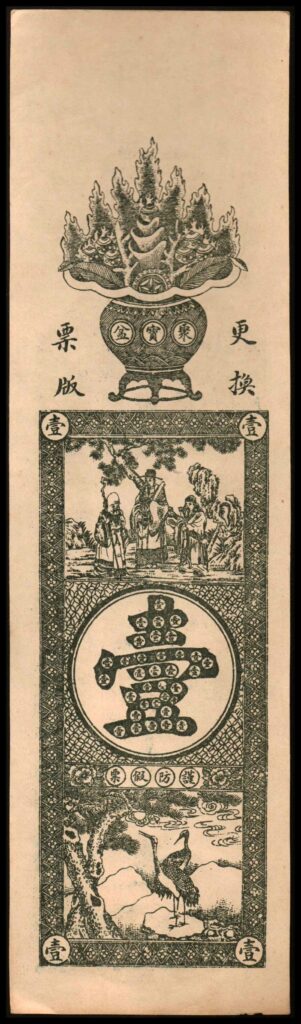

China Wanyuanhao Bank 1 Tiao

Wanyuanhao, in the city of Qingzhou, Shandong province. This particular note was issued by the Hongtai Lithographic Company. The characters in the center vertical line read downwards as: “Tong Yuan Quian Yi Diao Xheng”. The first three “Tongyuanquian” together mean Copper Money. Then “Yi Diao” is the denomination of 1 Diao (string). The bottom character “Zheng” means Exactly. So altogether it is: “copper money of 1 diao, exactly.” On the reverse of the note, there is a treasure bowl with four characters underneath meaning to “Beware of Forgeries”. The center character is a number 1 with multiple 1’s repeated within.

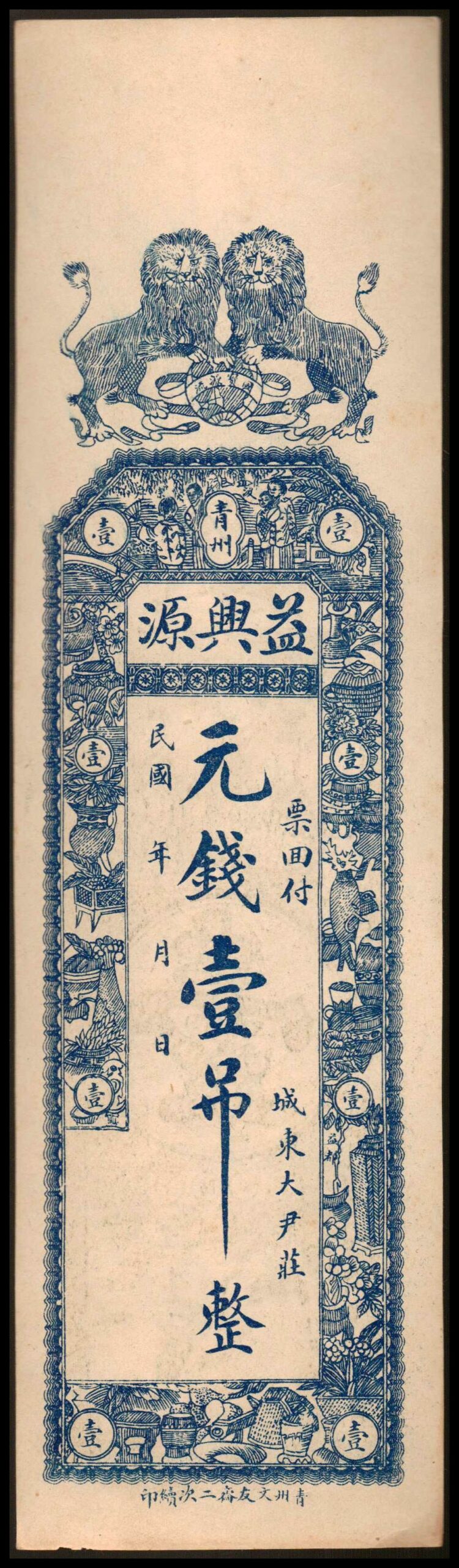

China Yixingyuan Bank 1 Tiao

issued by the company Yixingyuan, in Qingzhou, Shandong Province, and was printed by a company known as Wenyouzhai. The center characters are similar, but this one is missing the first character, “Tong”. Though it is missing, it is simply a shortened form of the same on the right, meaning “Copper money of 1 diao, exactly”. The reverse also has a treasure bowl, but it’s characters do not warn of forgeries, but rather inform the holder that this note was printed with a newer plate and is a second issue.

These notes are ‘remainders’, which are notes that were printed, but never issued. They lack the serial numbers, seals, etc., that would be typical to similar notes of the period.

They have printing differences that are distinct as the preceding notes are, with the line thickness, shading, and in the lower right, you can compare them and see that there is a table where there was only a bunch of flowers before. The lions on the top are also quite different in their artistic rendering. These were undoubtedly done by different artists, but as they were both issued in the same city, it is likely that the artists may have either known each other or were at least aware of each other.

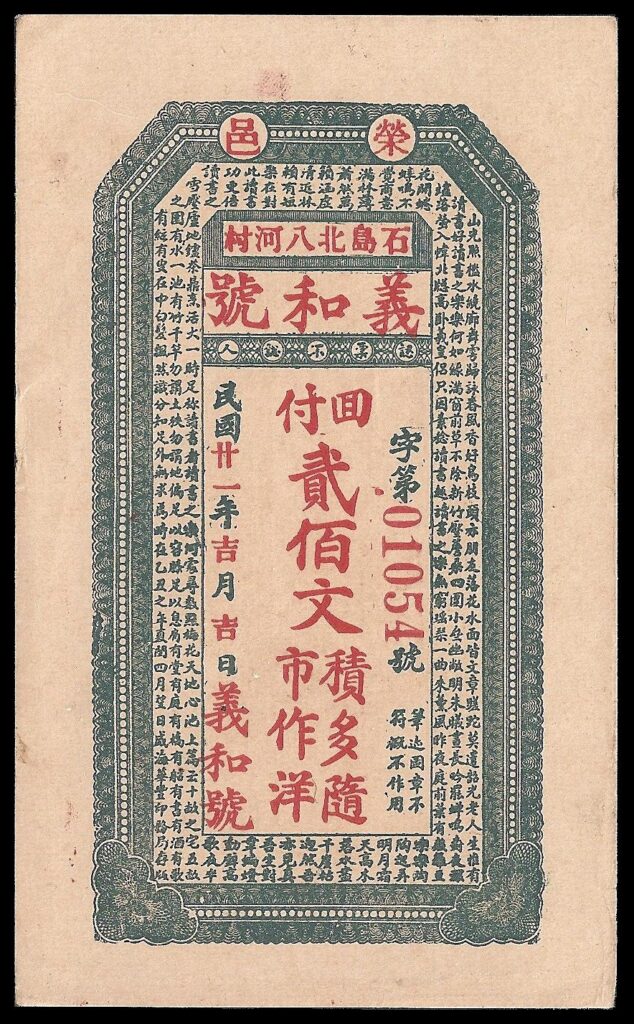

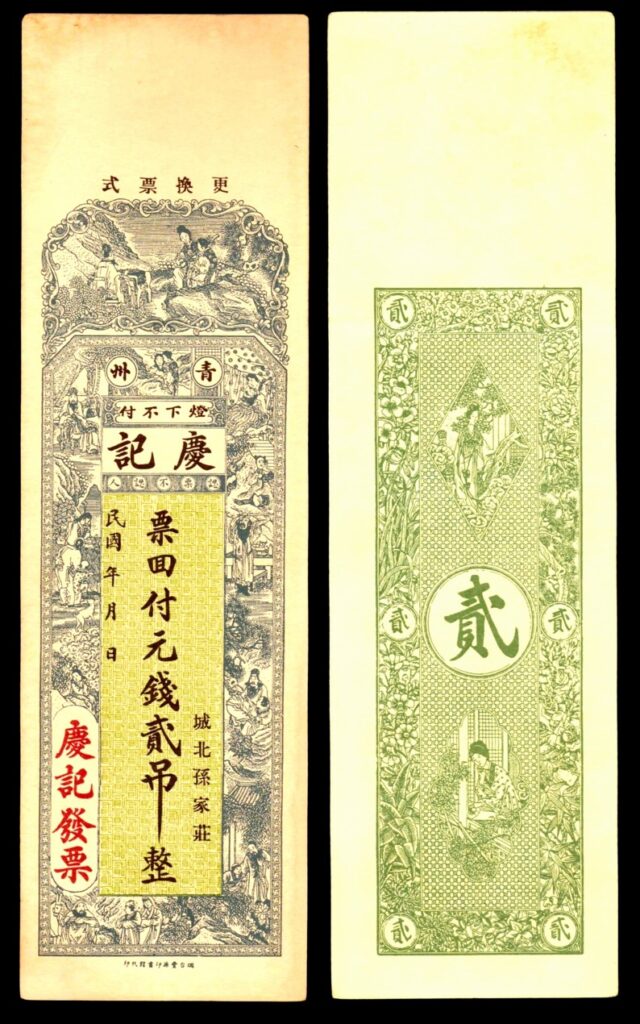

China Shanghai Yi He Hao 200 Cash

China Shanghai Yi He Hao 200 Cash – 1932.

You should compare the back with China 1000 Cash Local Note Wan Chang Yung – 1924 (several notes above). This reverse image shows an example of a notes vignette being reused for another issuing authority. While the overall design is the same, there are some size and style differences which are fun to compare.

China 1000 Cash – Printers sample

This 1,000 Cash, or Wen, was my first Chinese Vertical banknote in my collection. Looking closely, you’ll notice that the street scene on the reverse shows a rickshaw and a horse drawn carriage. This image was commonly used by several printers in China at the time. The note was issued by a company known as Deshengju, in the city of Wenyi (known as Wendeng, today), in Shandong Province in North Eastern China. Wendeng City, located at the eastern tip of the Shandong peninsula, has an industrial core, but most of the people work in the farming trade. It is across the Yellow Sea from the Korean Peninsula.

This banknote lists an address of the company in a rather curious manner. Anglicized, this is “Wen Dong Men Wai Yi”. The close observer will note that the name of the city, Wen Yi is located at the front and rear of the phrase. The middle of the address ‘Dong Men Wai” translates at ‘Outside the East Gate”, so Deshengju was a company located outside the city’s east gate.

The red letters along the left margin are “Deng Xia Bu Fu” or “No Payment Under The Lamp”, a standard clause listed on most banknotes. The meaning of this phrase is that you would not be able to exchange this note after the sun sets. “Under the lamp” was a phrase that meant “By Lamplight”, or “Darkness” when it was not possible to ascertain if the note was genuine, or one of the many counterfeit notes that were in circulation. Even though there were very strict laws concerning counterfeiting (beheadings and forfeiture of all property were not uncommon for government issued notes), the forgers were rife.

The note has a handwritten date of Year 10 (1921) and even a handwritten serial number. This curious piece is most likely from a printers sample book, as there are perforations along the side that are indicative of binding with string. Even if not from a sample book, the note is an un-issued remainder. An issued note should have the company’s seal in red located at the lower left of the note.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus,

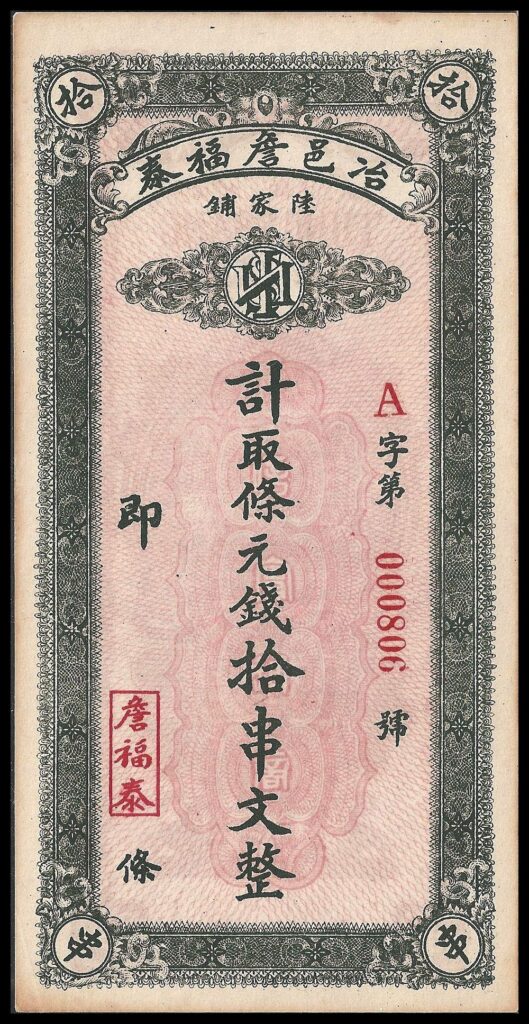

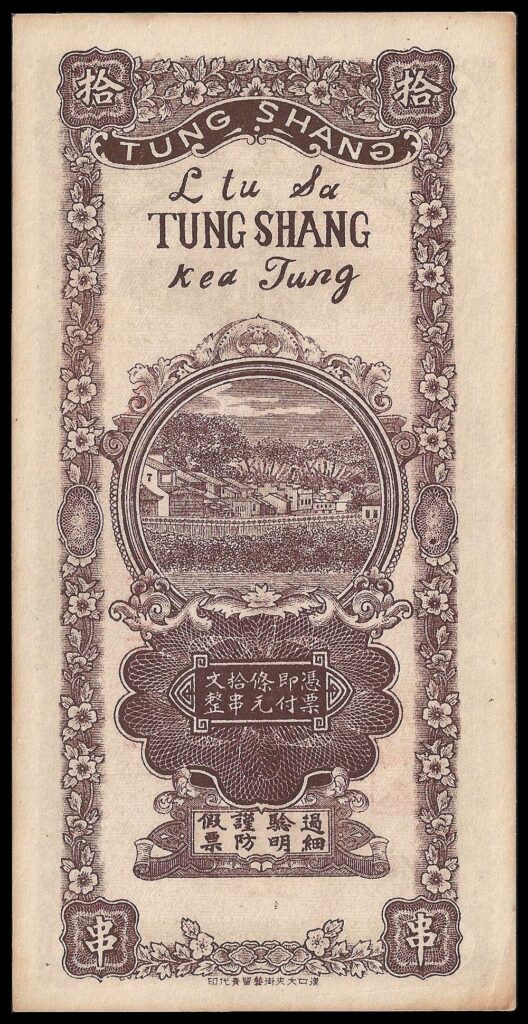

China Tung Shang Local 1920s – 10 String

China “Tung Shang” Local 1920s – 10 Chuan – with reversed ‘G’. This note was issued by a company called Zhanfutai. The company was located in “Yeyi”, a section of the city of Hangzhou, China. At the time this note was printed, the term “yi” of the word “Yeyi” denoted a governed sector similar to a county. However, later on in Chinese history, the “Yi” was changed to “xian”. This is now known as the County of Daye and is located in the Hupei Province.

Another locale is listed as Lujiapu. The suffix “pu” is generally used to denote a small town or village. This would have been located within Yeyi. Small towns such as Lujiapu were not required to change their names as were the larger governed areas. Lujiapu is still a very small mountain village within Daye, located east of Beijing City.

The reverse of this note has both Western text and what would appear to be Pinyin. What has come to light is that these words are meaningless, and that sometimes notes were given such western ‘flavor’. Perhaps they were placed there in an effort to give the appearance of western companies backing of the notes, thus making them accepted among the local inhabitants who thought they were more secure than a typical local issue. This is evident by the obvious fake words and the reversed letter “G”.

nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

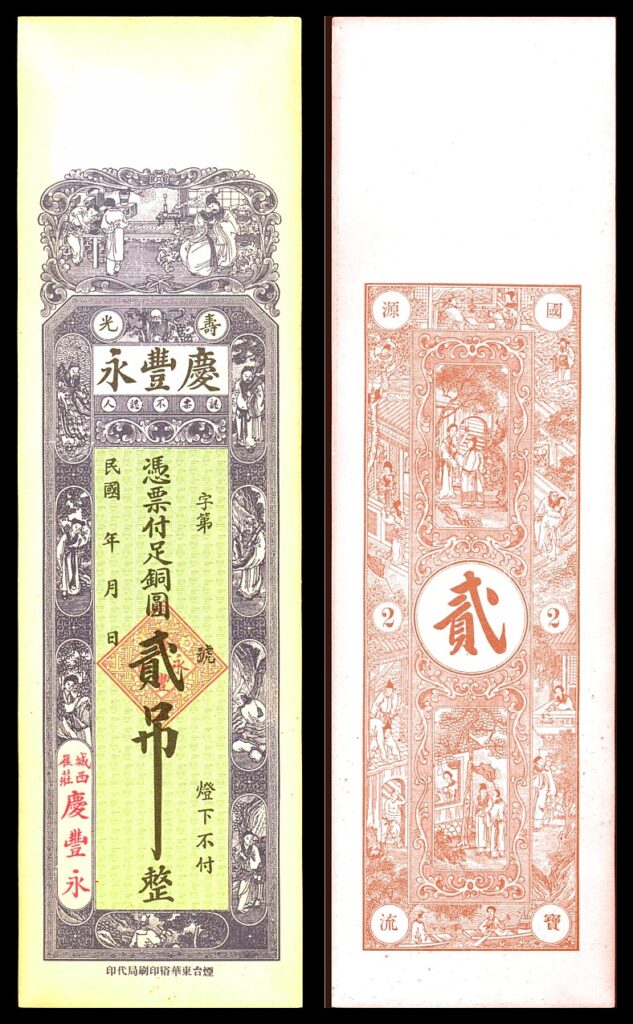

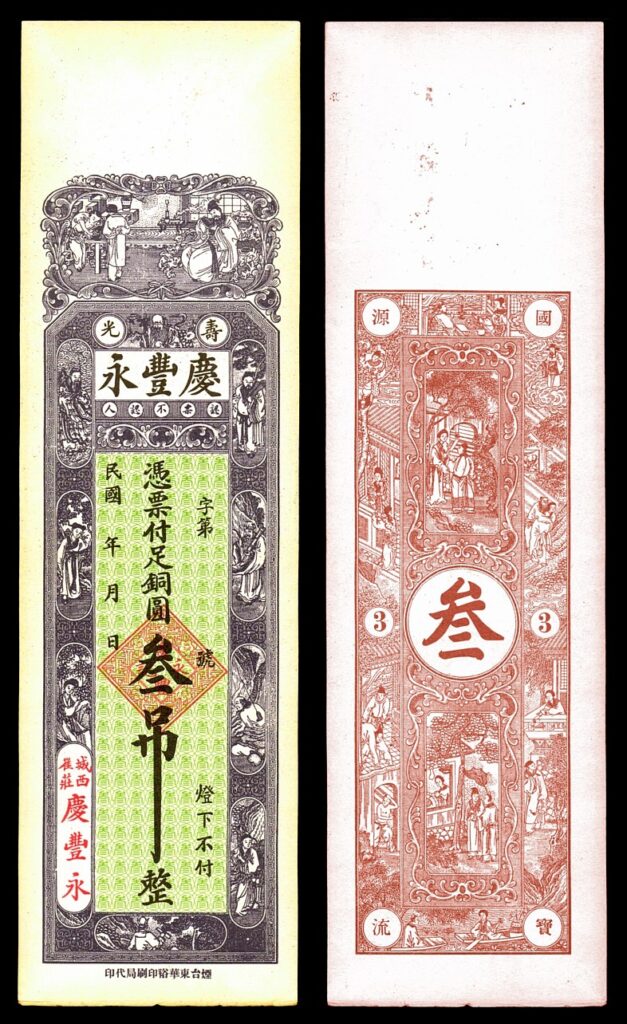

China 2 and 3 Tiao

These notes are unissued remainders of 2 and 3 string, or tiao. They have the denomination on the front, which denotes the value in Chinese, but on the back you will see that there is the Roman numeral on either side for western speakers, and in the center is a large Chinese symbol of the denomination.

The front of this note has a vignette that shows individuals in various activities. The back of the note shows people in what I can best guess is some type of courtship and consultation.

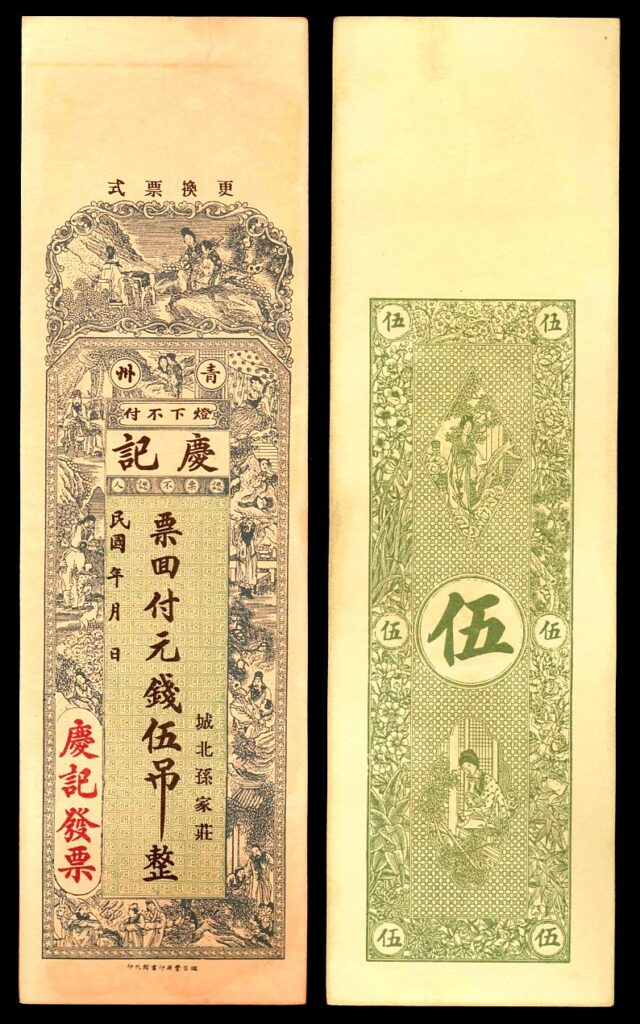

China Shantung – 2 and 5 Tiao

These two notes above are unissued remainder banknotes printed by Hing Kee company which was located in Quingzhou County in Shantung Province, China – on the eastern coast of China. The first one is a 2 Tiao denomination and the second one is a 5 Tiao denomination. The front of the note has a series of scenes including a trio of musicians at top, and people in nature settings around the border. The outermost border is made of bent crosses which in china are called “Wan”, meaning “everything’ or “eternity”. These predate the use of the symbol by the German Nazi Party and have no connection in their meaning.

At first glance, it would seem that, except for the denominations, the notes are identical, but closer examination shows the front, center green underprints contain different characters written in Seal Script.

For the next three notes, a bit of cultural history will help with understanding the figures and vignettes depicted on them. In Chinese mythology, it was said that there were three stars that manifested on earth as three elderly men. They were known as Fu, Lu and Shou and, according to their astrological significance, were known as gods.

Fu, or Fushen, was said to be the star Jupiter and was the god of happiness and luck. Fu was always depicted in traditional red clothing, and was very often shown carrying a scroll with the Fu symbol 福. At other times, he may be seen carrying a small child or being surrounded by children.

The reason that Fu was seen as lucky was because Jupiter was traditionally seen as a sign of prosperity and happiness. He is also identified with Yang Cheng, a governor of Daozhou from 206 BC to 24 AD. Yang Chen evidently wrote a letter to the emperor protesting the requirement that imposed on the people to send dwarf slaves to the imperial court. His letter worked and they did not have to send them as tributes afterward. Long after his death, his story morphed and he became associated with fortune and eventually merged with Fu. The children he is often seen with are likely more to do with the ‘dwarfs’ he saved from being servants in the imperial court.

Lu, or Lushen, was the handle of the Big Dipper, Ursa Major. Lu was the god of prosperity, rank and influence, and was shown in the dress of a Mandarin carrying a jade Ruyi. The Ruyi was a type of ceremonial scepter with the top part generally being in the shape of a heart or cloud. The handle was shaped as a flattened ‘s’ shape. Tradition has it that the Ruyi’s origin was from the common backscratcher, which gave the owner a sense of good fortune to be able to scratch his own back. The Ruyi is also called the “As you wish”, and was identified as a symbol of power and prosperity.

A Mandarin was a government official appointed through the imperial examination system. Rather than being specific tests for individual positions, the examinations were geared more towards knowledge of literature and classical knowledge, giving advantage to those who had a common language and culture. This method of promotion was said to greatly help China unify itself. “Lu” can also be translated as a governmental salary.

Another story about Lu is that he was originally a man who obtained a lower position in the imperial court. His hard work and willingness to learn eventually won him a top rank in the court. Lu is also seen holding an infant boy, which was also seen as prosperous.

Shou, or Shousen, was the star Canopus, the Southern Star in Chinese astronomy. He was carried for so long in his mother’s womb, that he was an old man when he was finally born. Yet another version of his myth states that he spent only 9 years in the womb. His beneficent attributes were health and longevity. He is typically portrayed as an old man with a walking staff made from peach wood in one hand and a peach in the other, but he is more easily recognized by his high forehead. The peach that Shou carries is magical and gives anyone who eats from it the gift of immortality. Shou is often depicted with bats, deer and cranes around him.

Shou is regarded as the more important of these three star gods because the gifts of Fu and Lu are best enjoyed with a long life.

The next two banknotes show these star-gods in central vignettes.

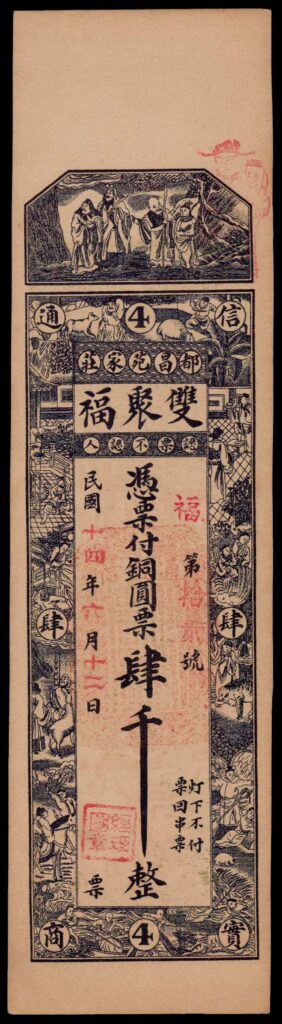

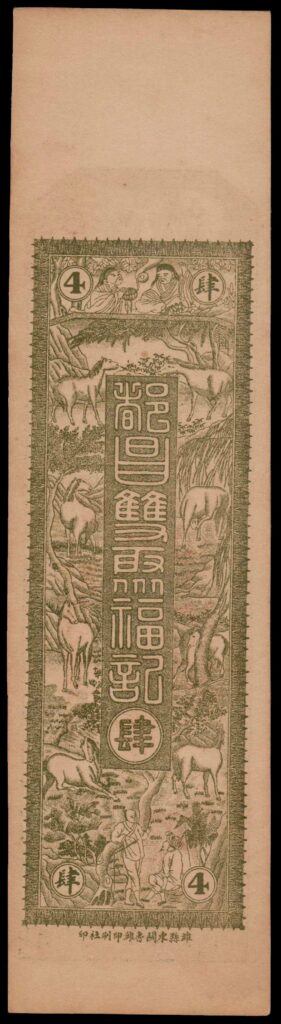

China 4000 Tiao

This note is an unissued remainder banknote from with a denomination of 4,000 string, or tiao. This note is different in a couple of distinctive areas. First there is the noticeable western numeral 4 placed at the top and bottom. The left and right center has the numeral 4 in Chinese. On the front you will notice that there are faint red overstamps, which are seals from issuing authorities. The top red seal is actually a depiction of a Fu the star-god of luck, holding a scroll. I’ve seen only a few of this type of red ink seal,

The front of the note depicts a series of scenes of what appears to be the story of Fu, Lu and Shou on the top of the note. The back of the note shows a series of horses and men.

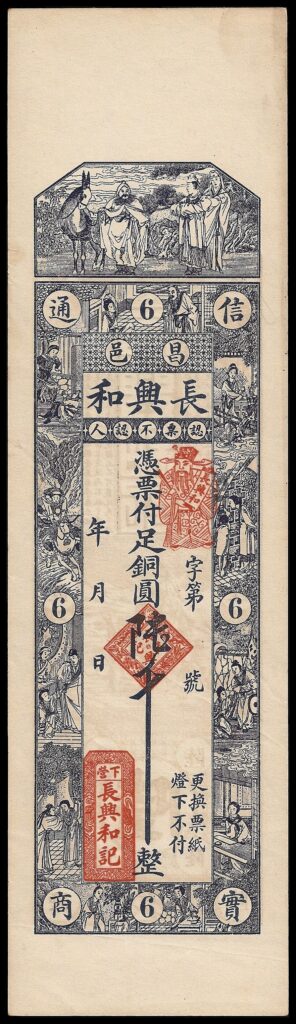

China Shantung, Chang Shing He Chi – 6000 Cash

This note is an unissued remainder banknote from Shantung, China and has a denomination of 6,000 Cash. As with the note above, there is the noticeable western numeral 6 placed in four spots on the front of the note: Top, bottom left and right. Again on the front you will notice that there are three red overstamps, which are seals from issuing authorities. Again there is the red depiction of a man holding a scroll.

One can see that the front of the note depicts a series of scenes of travelers, rural and household life. The back of the note shows more of the same’ There it also depicts the fable of Mu Guiying(穆桂英挂帅), the story of Yang’s daughters(杨门女将) fighting the Liao Dynasty.

China Kirin, Yu He Kong 100 Coppers – 1925

The note above is another unissued remainder, this one from 1925 in the city of Kirin, Yu He Kong (bank?) with a value of 100 Coppers. The banknote has an odd array of vignettes. From the bottom there are five people on clouds and the two on the ends have clouds rising above them which support other people, which repeats itself again and again, each person having clouds emanating from pipes, musical instruments, teapots, etc. until the very top which depicts two men with scrolls, who are representations of Fu, the star-god of luck and happiness. The top vignette shows a stag bearing a rider with a rather large head, accompanied by a rider at the rear. They are greeted by a boy offering a bottle while others mill about. These are Fu, Lu and Shou, the star-gods of luck, prosperity and longevity.

The reverse of the note shows a top vignette of people in western clothing as if in a park. The reverse main vignette shows a train and a gate to a temple.

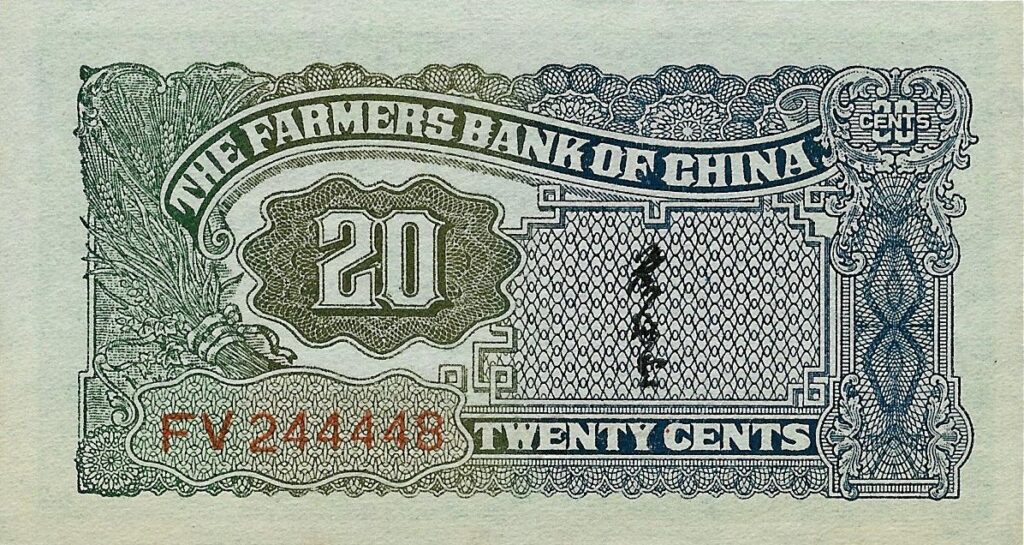

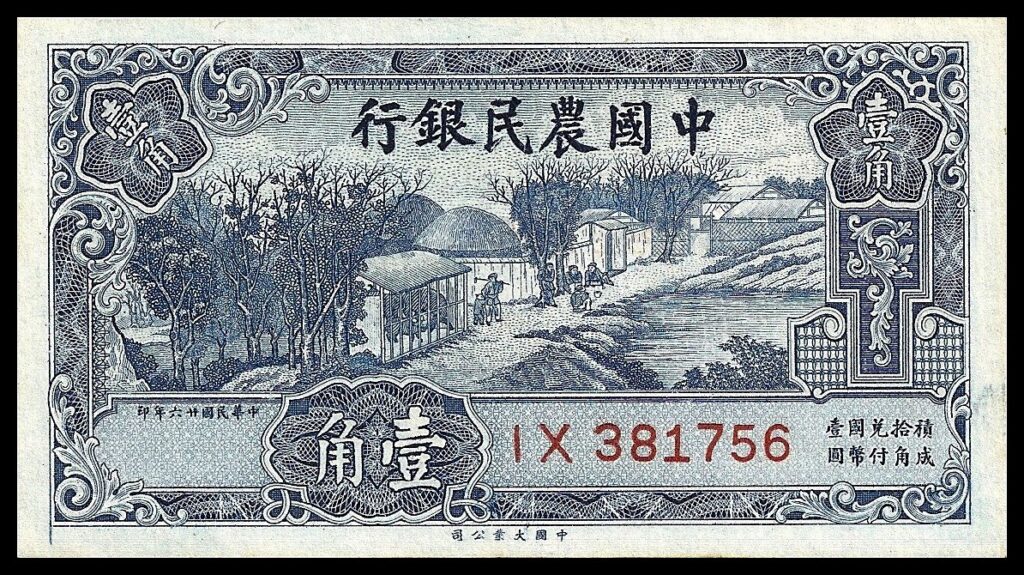

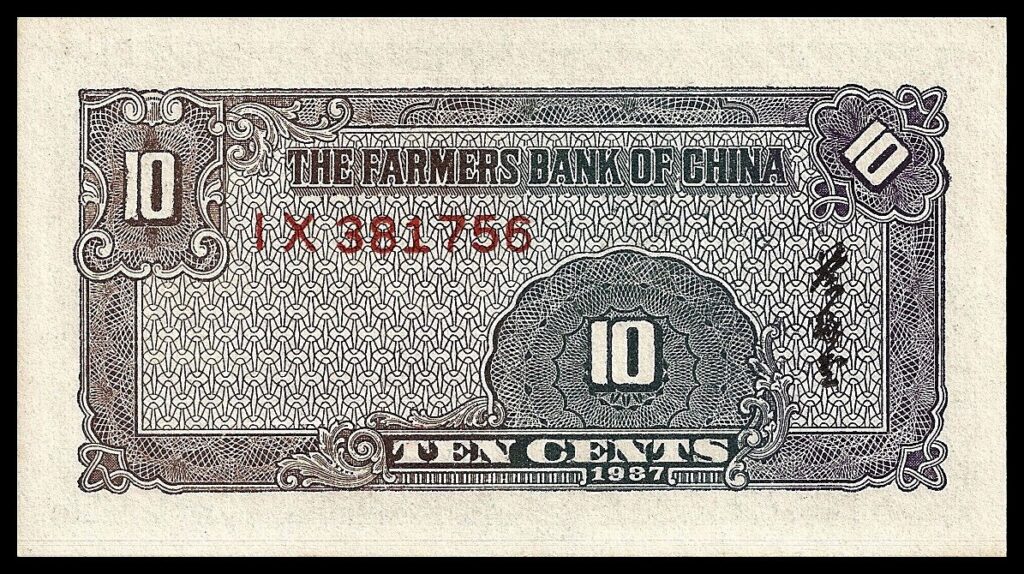

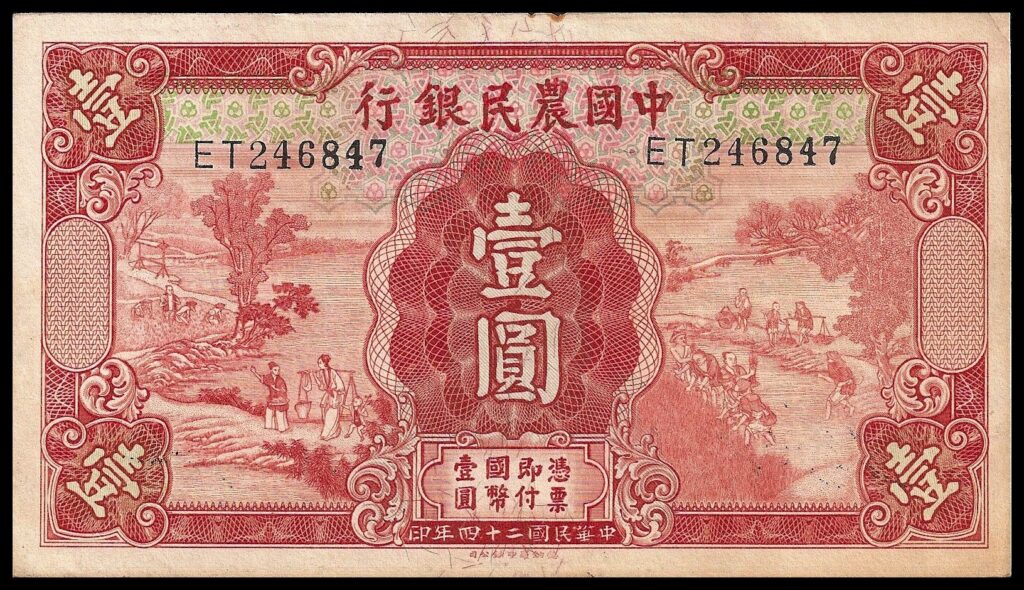

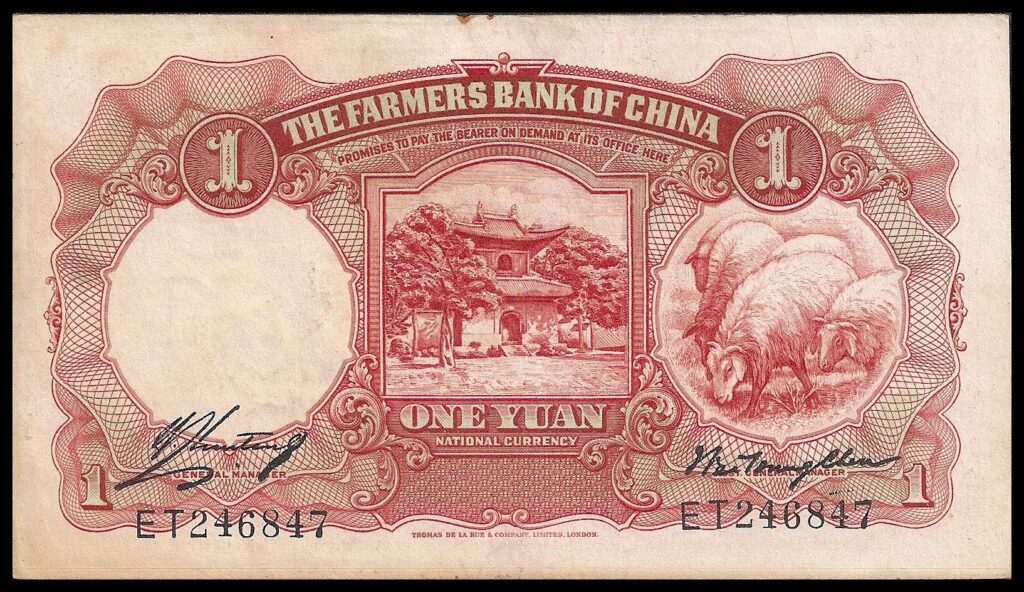

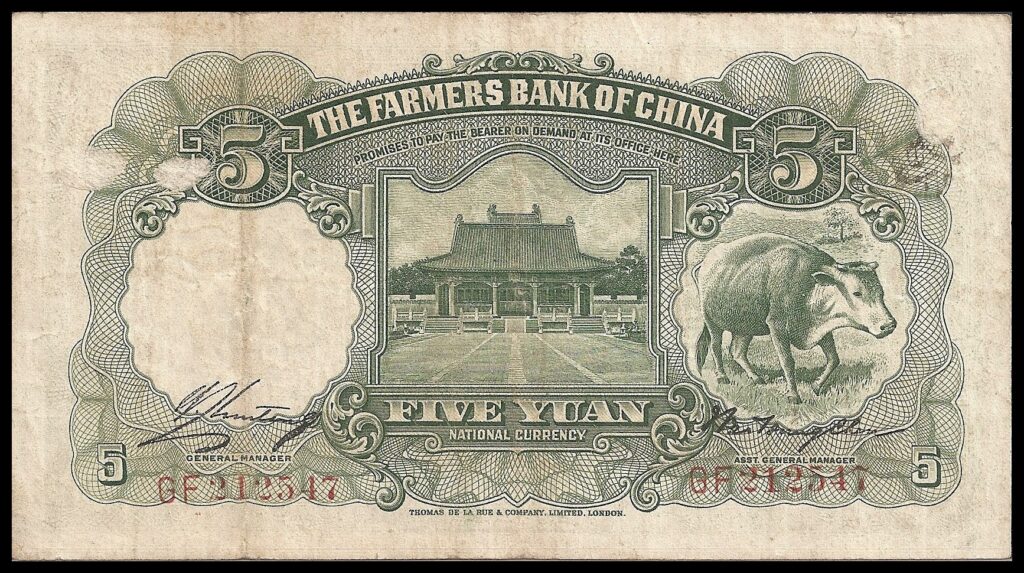

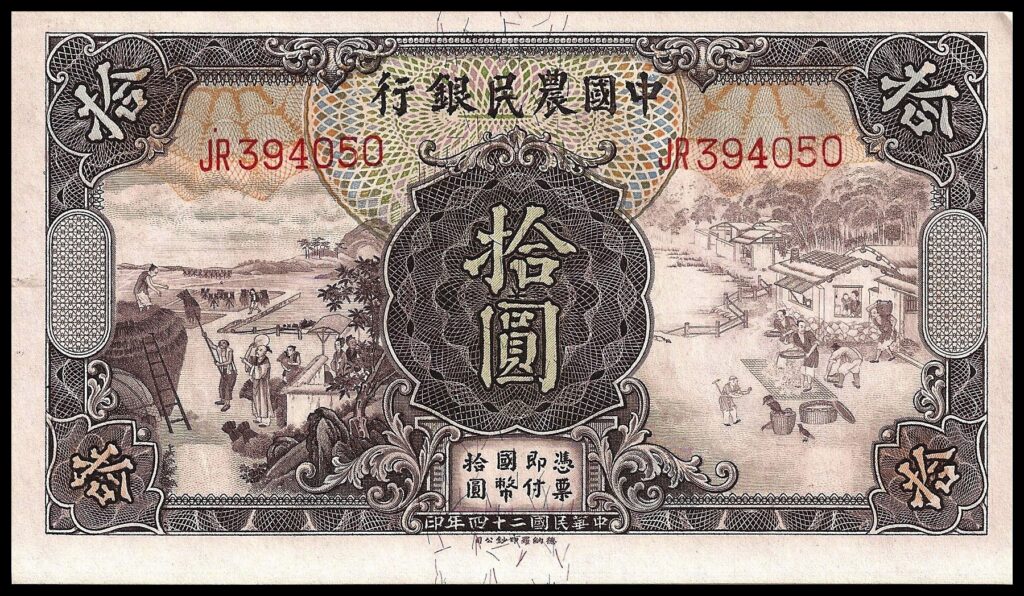

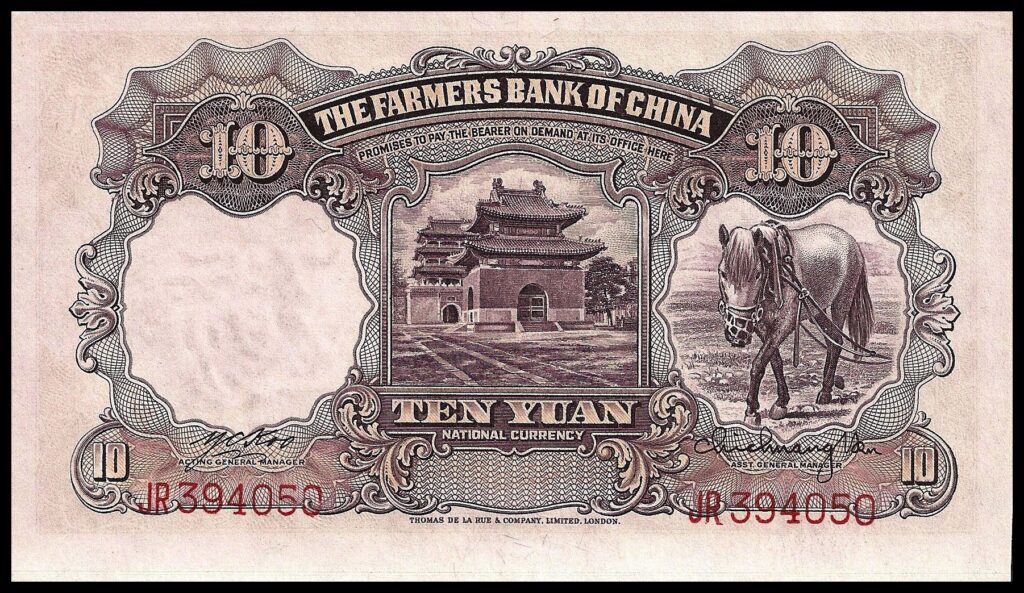

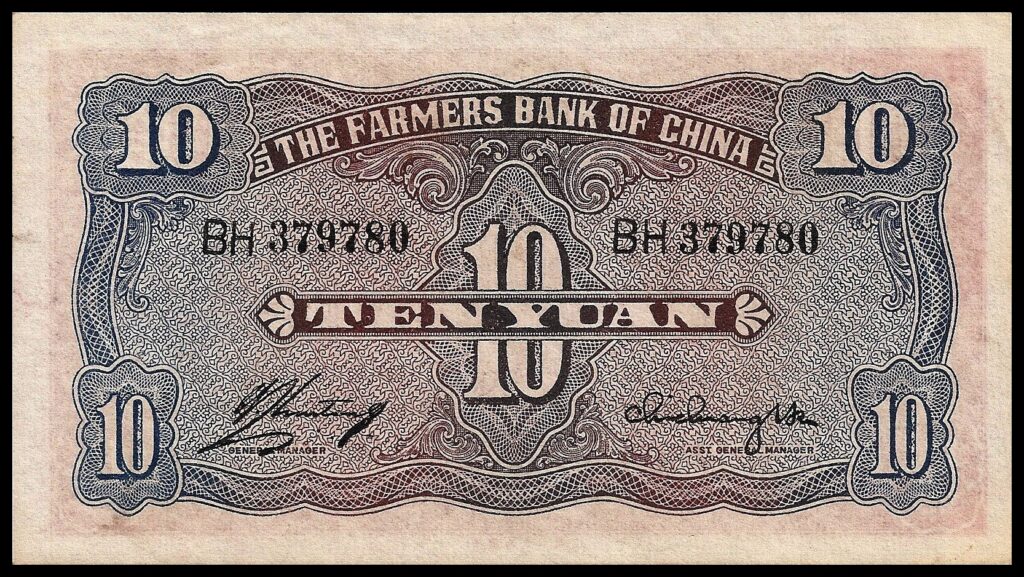

A series of banknotes issued by the Farmers Bank of China is another set of banknotes that I’ve found to be particularly appealing in their depiction of agricultural scenes. The quaint vignettes of these notes offer a historical, romantic view of older farming techniques, most of which are now accomplished with machinery.

The pattern is drawn from the 雍正耕织图 “Yong Zheng weaving”, which shows Emperor Yong Zheng within the scenes in ancient Chinese agriculture. In that time the status of an industrial farmer was considered most noble.

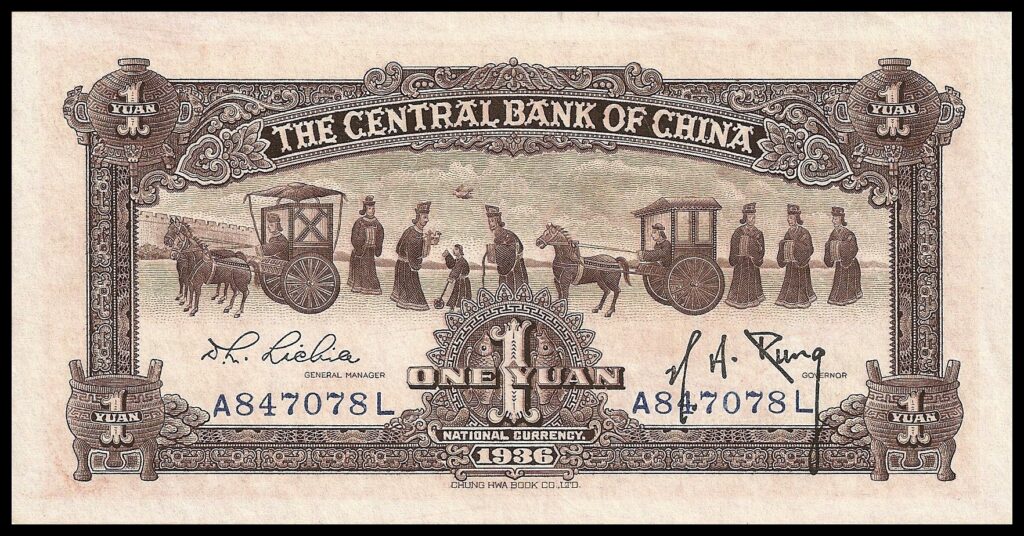

China 1 Yuan Central Bank – 1936

Above is a 1 Yuan note from 1936 depicting an older type of transportation. This note was printed by the Zhonghua Book Company. The reverse image actually comes from Jining, Shandong On Ziyun Mountain. Constructed in the first year of Emperor Huan of the Han Dynasty (147AD), it was originally called the “Wuliang Portrait” after the Wuliang Temple,

Confucius is depicted conversing with a young child on the reverse vignette of this note. This vignette relates an interesting story about Confucius being taught a lesson by a child named Xiang Tuo (Shang Too-o). It seems that one fine day while Confucius was out riding his chariots with his followers, he encountered a child playing in the middle of a road. The chariots stopped and Confucius saw that the child was making a sand castle, and ordered the boy to move aside.

The child, Xiang, was precocious and said back to Confucius: “When does a castle make way for a chariot? All the while, chariots must go around the castle to get to the other side.”

Confucius was amazed at the child’s reply and, perhaps feeling a bit challenged, asked the child a few more questions.

Confucius asked “Which mountain has no rock?”

Xaing answered “A sand mountain.”

“Which body of water has no fish.”

“Water in a well has no fish in it.”

“Which cow does not give birth?”

“A cow made of mud.”

“What type of man has no wife?”

“An angel has no wife.”

“What kind of woman has no husband?”

“A fairy has no husband.”

“Which city has no government officers?”

“An empty castle.”

Confucius was reported to be amazed at how this young child of 7 years age could be so wise. He decided to test the child further by playing a gambling game with him. The young Xiang refused and said: “A king who gambles will lead his kingdom into ruin. A farmer who gambles will lose his harvest. A student who gambles ignores his studies. I do not gamble. It is a useless activity – why should I learn?”

At this Confucius declared that the child was correct and that the young Xiang Luo was his teacher. He told his followers that even among three people, there will be a teacher, and that they must not be afraid to ask.