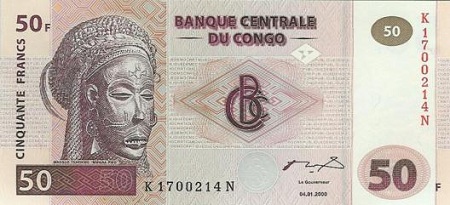

CONGO D.R.

Tshokwe Mwano Pwo Mask

The Tshokwe people’s history goes back to the 15th century when legend has it that a Lunda queen married a Lunda Prince. This was looked upon badly by the rest of the people, so these lovers exiled themselves south to what is now Angola. There are over 30 different spellings for Tchokwe the most encountered being: Chokwe, Bajokwe, Batshioko, Jokwe.

Their society is dominated by a separation of the males and females, Mugonge and Ukule repectively. Their social organization is based on matriarchal lineage. The use of the Mwano Pwo mask honors the founding female ancestor.

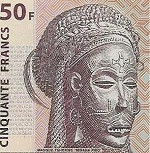

The Tshokwe carvers were renowned throughout the area. They produced a variety of ceremonial and utilitarian objects including statuettes, pipes, musical instruments, combs, snuff boxes, etc. Their masks were originally used in tribal ceremonies, but these days their use has been mainly for entertainment purposes. The two most popular are the Chihongo and the Pwo masks. The Chihongo is said to represent the spirit of wealth and the Pwo is supposed to be his lover. The Pwo masks were originally made of resin, but are today almost all carved from wood. Corresponding to the male Chihongo mask, the Mwana Pwo is generally more softly rendered, with the absence of a beard. The mask is considered to be sacred and personal, and to disregard the mask would invoke the anger of the ancestors. The Tshokwe carvings are readily recognizable due to their heavy features. There are no known examples of Tshokwe masks before the 20th century.

Traditionally the Pwo is archetypically female, and is often depicted as an elderly ancestor whose main purpose is to bestow fertility. The eyes are reduced to slits to mimic the deceased. The facial decorations are typically female. Later, the Pwo has been called the Mwano Pwo, meaning a young maiden who is ready to be wed. While the mask may be modeled after younger women the artist admires, their spiritual representation is of an ancestral matriarch.

One of the purposes of the mask it to teach the young women refined attitudes and feminine gestures and how to move gracefully and elegantly through the movements of graceful movement of the dancers.

The mask is worn by a man wearing a net tunic. The dancer sometimes pairs with a statue depicting a mother carrying a child on her back. The mask is also worn by boys undergoing initiation and other ceremonies to assist in fertility and prosperity. They dance with older male counterparts in an exclusive location away from the village. It is said that the boys learn of secrets that women are not to know, including sexual education, relationships with women, and how to support a family. They dance in braided fibers which completely cover the dancer, who moves in slow, precise steps to emulate a woman. The mask is sometimes said to represent the mother of the boys, and during this dance, the boys are ceremonially killed and reborn as men, no longer needing their mothers. Decorations of the mask typically include:

- Filed and pointy teeth

- Stylized hair

- White colors around the eyes indicating ability to peer into spiritual realms

- Eye sockets are typically large and concave

- Scarification and marking representing tattoos, of which there are four types:

- Cingelyengelye – a cross with triangles located on the forehead. This is thought to be passed down from Portuguese Capuchin monks who gave out medals of crucifix’s to the people in the area.

- Cijingo – depicting a spiral brass bracelet.

- Mitelumuna – a tattoo from the forehead to the temples meaning ‘knitted eyebrows’ and symbolizing discontent and arrogance.

- Masoji – located under the eyes symbolizing tears.