BELGIUM

Adolphe Sax

If one were to think of musical instruments as animals, the saxophone would be likened to the goose or swan. Its sometimes obnoxious ‘honk’ can be transformed into a beautiful, melodious tone, like the ugly duckling grown into a beautiful swan. From its beginnings, the instrument had some troubles, but it has become one of the most popular instruments, from marching bands to bar-playing cover bands, and classical music to its adopted home in American jazz. The instruments’ beginnings are perhaps unfamiliar to most of us, and it may surprise you to learn that the instrument that is an icon of the American jazz scene had its roots in very different soil, tilled by a man named Adolphe Sax.

Adolphe Sax was a Belgian who was born on November 6th, 1814 in the city of Dinnant, about 60 Miles southeast of Brussles, along the Meuse River. At the time of his birth, it was still a part of France, but would come under the rule of the Netherlands after the defeat of Napoleon in 1815. In 1830 the Belgian Revolution ended with the declaration of an independent Belgium, and Adolphe Sax and his family became some of the proud new Belgians.

Born to Charles Joseph Sax, Adolphe was the eldest of eleven children. His given name was Antoine- Joseph sax, but was called Adolphe from birth. Life in those times was difficult and dangerous, and Adolphe had his share of experiences of both. While still a child, he suffered many close calls, including swallowing a pin, burned in a gunpowder mishap, burned again by a frying pan after falling onto a stove, overcome three times with varnish fumes, knocked in the head with a cobblestone, almost drowning in the river, he fell three stories from an open window and he evidently swallowed some sulfuric acid. While he was lucky enough to survive those mishaps, it was perhaps a portent of the troubles he would encounter during his life as an adult.

As a young man, Adolphe apprenticed as a carpenter under his father, Charles. Charles was fortunate enough to have won a contract to provide some musical instruments to the Dutch army, and it was in making these instruments that Adolphe had shown his greatest promise. In addition to learning the trade of his father, Adolphe also studied music at the Royal Conservatory in Brussels (École Royale de Musique), taking lessons in voice, flute and clarinet. While still working for his father, he began to experiment with new instrument designs, and before long, in his 20’s, he developed a great improvement to the bass clarinet, replacing the open holes with keys, increasing the diameter, and adding a sound reflector to the bell.

At age 26, in 1840, he presented several of his innovative instrument designs at an exhibition. Of note were an organ and a sound reflecting device along with a new piano tuning system. His ideas were so well received that he was considered for the exhibitions gold medal, but his young age set him back. The Gold medal was given to someone more appropriately aged in the judge’s opinion, while second place, a gilded silver medal, was issued to Adolphe.

In 1841 Adolphe had an idea and plenty of inspiration, and he set out for Paris with only 30 francs to his name. With almost no money, Adolphe was forced to live for a while in a shed and take out loans to set up his shop. His borrowed money was stolen, leaving him with debts owned and no gain. He had plenty of rivals as well, who plagued him with thefts and legal claims against his ideas, causing him to continually respond to their attacks without being able to make his claims at the patent office. With the help of the composer Fromental Halévy, known for his opera La Juive, Adolphe met Hector Berlioz, a composer and critic of the modern music scene. Adolphe lent Berlioz a new instrument – the Baritone Saxophone – for him to try out and give his critique.

The saxophone was unique. It was strong voiced like a brass instrument, yet it could emote the expressive, almost vocal sounds of reeded instruments. It did not take long for Sax to receive Berlioz’s opinion of his new instrument. The following morning, Adolphe picked up a copy of the most popular newspaper in France at the time, Journal des Débats. Within its pages was Berlioz’s review of Adolphe’s Sax and of Adolphe Sax himself:

- “…A man of lucid mind, far-seeing, tenacious, steadfast and skilled beyond words, he is ever prepared to replace the workers incapable of understanding his projects or realizing them, whatever their specialties. He is a calculator, an acoustician, and when required, a smelter, a turner and, if need be, at the same time an embosser.”

- “…the character of such sound is absolutely new, and does not resemble any of the timbres heard up till now in our orchestras…”

- “The composers will be very indebted to Mr. Sax when his new instruments are generally employed. If he perseveres, he will meet with the support of all friends of music.”

Adolphe was probably worried about the review, but one can imagine him spilling his morning coffee while jumping up in excitement at reading these passages. The wonderful review began to change his fortunes as musical scores were being written for the new instrument and orders for instruments came in. It is said that each man is the author of his good fortune, and Adolphe had sought for and achieved that which he sought to do. But it was not all wine and roses.

There were some musicians, understandably preferring their old instruments, who refused to play his new saxophone and improved clarinets. Then, in another exhibition in Paris, a German bandleader named Wilhelm Wieprecht tried to malign Adolphe by claiming that it was not Sax who created the Saxophone, nor improved the bass clarinet, but rather a pair of German musical inventors. They even bought some of Adolphe’s instruments and sanded off Sax’s engraved logo, presenting them as evidence that he had not produced them. Adolphe was furious, but could do little to contradict the claims made by the then famous Wieprecht. Worse yet, he could not pursue his patent under these allegations. But Adolphe also had a few friends in the right places.

In 1845 there was a celebration in Germany where a statue of Back was to be unveiled. A few days after the celebration, there was to be a concert in the city of Coblenz, where the renowned Jenny Lind, known as the Swedish Nightingale, was to perform. Many prominent musicians showed up to take part in her special concert, including Franz Liszt, Wieprecht, Adolphe Sax and Paolo Fiorentino, a correspondent for the Paris Constitutionnel. According to Adolphe Sax and his Saxophone by L. Kochnitzky, when Wieprecht came into Liszt’s room, Liszt knocked on the wall, and in came Adolphe Sax. The two looked at each other and Adolphe asked:

“Really, do you know anything of my instruments”?

“I know everything” Wieprecht answered modestly.

“The Saxophone, also”? Asked Sax.

“Ja wohl”

“And my bass clarinet”?

“Ja.”

“And could you play it”?

“Ja.” Answered Wieprecht.

Then Sax produced his instruments and offered them to Wieprecht to play, which of course he couldn’t. He didn’t even know how to hold them properly and, try as he might, he could make only the most pathetic of sounds. Wieprecht was beaten, but managed to be beaten gracefully. He apologized profusely, and offered Adolphe to come to a concert hall to hear the German instruments and to demonstrate his own for the German band. After his vindication, Adolphe Sax received his patent the following year. Now that he was old enough (in the judges eyes, anyway) he also won a gold medal at the 1849 Paris Exposition. At last, Adolphe must have been feeling vindicated and on the road to success with his saxophone leading the way in his own parade.

The new saxophone was selling wonderfully, and Adolphe’s shop in Paris was doing quite well at this time. In fact, Adolphe was able to hire his father to be the production manager for his Paris shop. From 1843 to 1860, there were an estimated 20,000 of his instruments sold, an average of 1,176 a year. His production problems may have been behind him, but fiscal responsibility was not his forte. It did not help that he still had rivals who were attacking him with legal claims against his patent that he had to keep fighting. Adolphe filed for bankruptcy three times in 25 years. To add further to his troubles during this time, Adolphe started having some trouble with his lip; the doctors diagnosed it as cancer. The diagnosis would be fatal under normal circumstances of the time but, as in his younger years, he was able to stave off death, and he made a full recovery.

While he may have had the ability to recover from accidents and illness, Adolphe’s monetary problems endured. It was on the eve of his fourth filing for bankruptcy that he received assistance from none other than the Napoleon III. Actually, it was due to Napoleon’s aide-de-camp, Colonel Fleury, who was a friend of Adolphe. Fleury urged Napoleon III to give Adolphe Sax a contract to build instruments for military bands at the rate of 20,000 Francs per month. This helped considerably, but once the contract was over, the money woes continued. He did manage to obtain a teaching position at the Paris Conservatory however, and Adolphe managed to barely keep himself afloat for a while.

Adolphe never managed to achieve financial stability, despite his success at getting his instrument accepted by many in the musical society. His teaching position ended in 1870 and he lived in close proximity to poverty until his death on February 7th, 1894, and was buried at Montmartre Cemetery in Paris. During his 80 years he was able to get the instrument accepted by many, but it wouldn’t be until the 20th century when the instrument would travel further, across the oceans and become a standard instrument in American music, jazz in particular. Though still not a staple instrument in orchestras, it is known worldwide by sight and, of course, it’s sound.

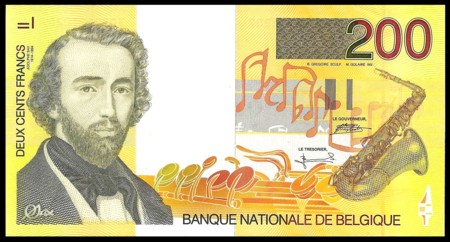

Perhaps his woes were quelled by the other love of his life, Louise Adele Maor. Though they were never married, they had a son, Adolphe Edouard Sax. His son followed him in the instrument business, just as the elder Adolphe did with his father. His son was able to keep the saxophone business until 1928 when it was bought by the Selmer Company, still in business today as the Conn-Selmer Company. In 1995 Adolphe Sax was commemorated on the Belgian 200 Franc banknote. The note is predominately yellow-gold, relating to the brassy color of the saxophone. The front of the banknote has Adolphe’s portrait prominent at left with his instrument in full at right. A detail of the keys is shown at bottom with loosely written musical notation. The back of the note has outlines of three saxophone players, and depictions of a church and houses in his hometown of Dinant.