BRAZIL

Candido Rondon

Candido Mariana da Silva Rondon was born in the small town of Mimoso, north of the city of Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul state, in Brazil. His father was of Portuguese decent and his mother was from the indigenous Bororo tribe. By the time he was two years of age, Candido Rondon had lost both his parents and was taken in by relatives and grew up in Cuiabá, about 150 miles north of Mimoso. He graduated secondary school at 16, but as there was no university in the area at that time his choices for continuing his education were the seminary or the military. Candido Rondon chose the latter and enrolled into military school in Rio de Janeiro in 1881, graduating as a second lieutenant in 1888.

During his first year as a young army officer, Rondon helped in the overthrow of the Emperor, Pedro II, and usher in a democratic republic. But though Rondon could have possibly pursued a path following this line of patriotism, he did not. The following year, Rondon received his degrees in mathematics, physical and natural science. He was soon after promoted to Military Engineer, which was an accomplishment most would be envious of, ensuring a post in Rio de Janeiro as a professor for the rest of his life.

In 1890 he was teaching astronomy, mathematics and mechanics at the military school, but he left when the opportunity arose to help build a telegraph line across the Brazilian interior. He spent five years leading his men through the jungle, erecting lines across the countryside, bringing the modern communications of the time to Mato Grosso. His work with telegraph lines earned him the title “Father of Brazilian Communications”. When this telegraph line was finished, he helped to build a road linking Cuiaba in Mato Groso, to Rio de Janeiro. In 1892, he met and married his wife, Chiquinha Xavier of the Bororo People. She accompanied him on his travels through the jungles, and together they had seven children, one son and six daughters.

After the road was finished, he spent six years installing telegraph lines from Brazil to Bolivia and Peru, and continuing to encounter many indigenous peoples. He had a knack for pacifying the tribes, and even had the Bororo tribe assist him in laying out telegraph lines. His successes in laying the telegraph lines earned him another route: into the Amazon. It was here that he had officially discovered the Juruena River, until then only a legend.

Rondon made many expeditions into the interior during his lifetime. He always took two parties: A team of construction workers, and a team of scientists, including zoologists, linguists, ethnographers, and geographers. Rondon led the Geographers team and surveyed the land and rivers. His other scientists helped to collect over 3,000 indigenous artifacts, catalog 5,000 species of Flora, and 8,000 fauna species.

A great part of his success in making peace with the tribes was due to his motto: “Die if necessary, but never kill.” Rondon, a Brazilian army officer of distinction, was, above all, a humanist. He understood that while the Indians were living as barbarians without modern conveniences or knowledge, they were still human beings and desired to better themselves as all humans do. Upon encountering a new and often violent tribe of Indians, Rondon would leave metal tools as peace offerings and retreat from the area. With each encounter, he repeated this several times until he gained the confidence of the tribes as a peaceful man and would then enter into dialog with the tribes, making a peaceful pact. Most of the time it worked, but there were several times when his methods would fail due to the inherent mistrust of tribes who remembered earlier invasions into their territory, killing Indians and ruining villages. It was during his work in the Amazon that he encountered the Nambikwara tribe, a particularly violent people who were infamous for killing all westerners they encountered. His efforts to leave presents were unappreciated and they were attacked. One arrow grazed Rondon’s face and another embedded itself into his belt. He fired shots into the air, showing that he did not wish to kill the tribesmen. The Namikwara then saw he ment no harm, and he was able to broker a peace with them. Rondon lived by his motto, and so did his men. During his expeditions, he lost over 150 men, but this was far fewer than there would have been had he employed a warrior methodology and tried to defeat the people he encountered in their own environment.

In May of 1909 Rondon embarked from the village of Tapirapua in Mato Grosso, and headed toward the Madeira River, the longest tributary of the Amazon River. Within three months, Rondon’s party had exhausted their supplies and were forced to survive by hunting and gathering like the indigenous people he so often tried to help by giving tools and knowledge to during his encounters. The outlook was bleak for Rondon and his party, but they pressed on. Eventually they found the Ji-Parana River, and followed this to a new discovery: another river which, not knowing where it would lead them or if they’d survive, he named Rio da Duvida, the River of Doubt. This new river led them to the Juruena River which he had discovered earlier. Having spent seven months out in the wilderness, they eventually found their way to the Madeira River on December 25th, 1909.

Back in Rio de Janeiro, such a long time had passed, that Rondon’s party was thought to be lost in the wilderness, and was presumed to be dead. But his return earned him more honors, and he was confirmed as the first director of the Brazilian Indian Protection Service, Serviço de Proteção aos Índios, or SPI. This agency was set up to protect the Indigenous peoples and their cultures.

Rondon took his position to heart. He spent his time with the SPI working for the rights of the indigenous people of Brazil, demanding that the army protect them, officiating the tribal boundaries and deeding the land to them legally. He ensured the tribes had their cultures protected by guarantees of the state to protect their religious views, livelihood, and to learn to use modern tools at their own pace. They would be given teachers, but they would not be subjected to conversion by missionaries. The tribes were given metal tools, taught how to weave, given medicine and salt to preserve foods, etc., all in an effort to help them improve their lives. Rondon ensured there was no effort to convert or to assimilate the tribes.

In 1913, after American President Theodore Roosevelt had lost his last bid for the White House, Roosevelt needed a distraction. In an effort to forget his loss, he accepted speaking engagements in Argentina and Brazil. He was going to end his trip with a cruise along the Amazon River. The Brazilian government offered him a different itinerary, however. Roosevelt had already accompanied John Muir to Yosemite in 1903, and they offered an expedition with Brazil’s greatest explorer, Candido Rondon. Roosevelt accepted.

Together with his son, Kermit, and American Naturalist George Cherrie, Roosevelt joined with Rondon and his team to explore the river Rondon had only recently discovered: The River of Doubt.

They began the expedition in Caceres, (aka Porta do Pantanal) on Brazil’s eastern border, and headed up to Tapirapua, to the headwaters of the River of Doubt. They trekked through the jungles and plains until February 27, 1914 when they reached the River of Doubt, out of supplies and food. In fact, from the beginning, the expedition was fraught with peril. Malaria and insects plagued everyone on the team, the food was not enough, and the indigenous tribes eyed the expedition, bringing a sense of fear to the team. It was undoubtedly Rondon’s efforts at pacifying the tribes that ensured the safety of Roosevelt and his party from the previously hostile Indians.

Canoes were lost and had to be re-hewn from trees. Injuries and fever slowed the expedition down to a crawl. The expedition split up. One followed the Ji-Parana to the Madeira River, while the other team, with Roosevelt and Rondon, headed down the River of Doubt. Roosevelt had an infected leg wound and was continually getting worse and his survival of the expedition was soon a constant doubt itself. Fortunately for the team, they encountered a band of rubber tappers, local inhabitants who were collecting rubber for American tire companies. The expedition was guided by the locals along an easier route along the River of Doubt and Roosevelt survived, though his health always suffered from his injuries and sickness from this trip. Rondon renamed the River of Doubt the Roosevelt River in his honor.

Roosevelt was able to give Rondon international recognition when he acclaimed him as a scientist and humanitarian. This expedition also spurred The American Geographic Society to award Rondon the Livingstone Prize for exploring the deepest into tropical terrain.

Candido Rondon was not finished yet, however. After the expedition of 1914, Rondon worked until 1919 mapping the state of Mato Grosso. During this time he discovered some more rivers, and made contact with several Indian tribes. In 1919, he became chief of the Brazilian Corp of Engineers, and the head of the Telegraphic Commission. He was working on a project of mapping the Brazilian border when the Revolution of 1930 broke out. This stopped his project and he was called to take part in the bloodless coup.

But Rondon had changed from the days when he was a young army officer, and he wanted no part in politics. This was enough for the new government to start lobbing attacks at his character. Rondon’s fear that these attacks could affect his work with the SPI caused him to resign his post there. However, with Rondon no longer at the helm, the SPI was soon influenced by bureaucrats, industrialists, and profiteers. The SPI has its funding slashed, and its policies soon became a mere trifle to circumvent. The lands and peoples Rondon worked to protect were soon being plundered and killed. Many tribes returned to the forests and prepared to fight the new invaders.

Yet Rondon’s efforts were well known throughout South America, and in 1934 he was tasked to use his skills at pacifying indigenous tribes to the international realm. He was appointed to the League of Nations to broker a peace treaty between Peru and Colombia over a border dispute involving the small town of Leticia. It took four years for the two countries to succumb to peace, but Rondon’s efforts with the League of Nations paid off. He was reinstated as the Director of the SPI, and he began to resume its efforts, trying to stop the plunder and killing that had been going on. Perhaps inspired by Theodore Roosevelts creation of National Parks in the United States, Rondon created the first Brazilian National Park, Xingu Indigenous Park, which declared vast regions and their resources to belong to the indigenous people.

He continued to work tirelessly for indigenous people, the remainder of his life. In 1952 he founded the Museum of the Indian in Rio de Janeiro. At the age of 90 the National Congress of Brazil promoted him to Marshal, the highest military rank, and named a state after him: Rondonia.

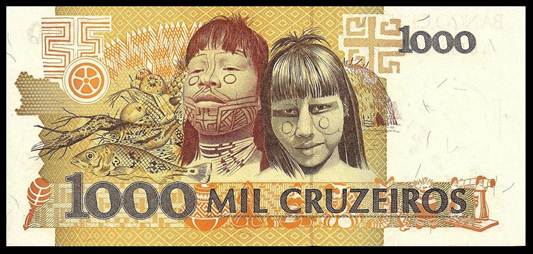

Candido Rondon died quietly in Rio de Janerio in 1958 at the age of 92. He is memorialised on this 1,000 Cruziero banknote issued in 1989.