ENGLAND

Elizabeth Fry

Elizabeth Fry was born as Elizabeth Gurney into a devout Quaker family in Norwich, England on May 21st, 1780, the third of what would eventually be 12 children. Her father, John Gurney, who was a part owner of a wool spinning factory and her mother Catherine was from the same Barclay family that founded the famous Barclay’s bank. Being quite well-to-do financially didn’t seem to spoil the children too much, as the spiritual nature of the religious tone of the household exposed the children to philanthropic activities and at least two hours of silent worshiping a day. At the age of 12, Elizabeth’s mother died while giving birth to her last child. As the eldest daughter, Elizabeth had to take charge of the younger children of the household.

As a young woman Elizabeth had met several influential people through her family’s connections. Among them were Mary Wollstonecraft, an ardent advocate for women’s equality, and Thomas Paine, the American writer of “Common Sense”, which gave very strong reasons as to why Americans should seek freedom from Great Britain. While Thomas Paine was an American revolutionary, Mary Wollstonecraft spent most of her time in England, creating controversy by claiming equal rights and citizenship of the sexes, and coeducation on an equal basis for boys and girls. At the age of 18 Elizabeth Fry attended a sermon of a travelling preacher from America, William Savery. Savery was not only a Quaker minister, he was a furniture maker of great repute; some of his works have even been on display in the New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. His words on equality for all mankind spoke to Elizabeth’s heart and, after meeting with him, Elizabeth decided that she would devote her life to helping others who were less fortunate.

She started charity drives for clothing the poor and began a Sunday school in her house, teaching children how to read and write. Her actions led her to be named to run the Quaker School in Ackworth, England.

In 1799 Elizabeth met Joseph Fry, a banker, and more importantly, a Quaker. They fell in love and were married on August 19, 1800, and moved to London, where Joseph worked as a merchant, but would soon open his own bank. Maintaining her passion for religion, the following year Elizabeth became a preacher for the Society of Friends. Over their life together, Elizabeth and Joseph had five sons and six daughters.

Elizabeth and John had a friend named Stephen Grellet, an active Quaker missionary in prisons and hospitals across Europe and America. Grellet, a French aristocrat that had escaped persecution by fleeing to America, was in England on one of his missionary trips, and he visited London’s main prison, Newgate, where condemned prisoners were kept prior to execution. Newgate Prison was well known then, and is now remembered for, the executions that were held there. As was tradition, on the eve of the execution, a bellman from the church outside Newgate Prison, St. Sepulcher’s, walked through an underground passage to Newgate Prison, ringing twelve double-tolls while chanting:

“All you that in the condemned hold do lie

Prepare you, for tomorrow you shall die

Watch and pray, the hour is drawing near

That you before the Almighty must appear

Examine well yourselves, in time repent

That you may not to eternal flames be sent

And when St. Sepulchre’s bell tomorrow tolls

The Lord above have mercy on your souls”

The executions always took place on Monday mornings at nine o’clock, following the first toll of the Church’s tenor bell.

Grellet told them of the appalling conditions that were inside, where prisoners were kept indiscriminately, mixing hardened criminals with those still awaiting trial. They heard him speak of bad food, poor health conditions, and how the prisoners had to sleep on the ground. Stephen Grellet asked to see the women’s side of the prison, but was told by the authorities that it was even worse than the men’s side, that the women were even more unruly, and they could not guaranty his safety. Grellet insisted, and the stories he told of his visit made Elizabeth’s heart sink, and she decided to visit Newgate prison to see for herself. Inside she found about 300 female prisoners, some with children in tow, as they had nowhere else to go. They were kept in cells in which they had to sleep, cook their own meals, wash and sleep. Elizabeth felt for the women and wanted to help them somehow. Unfortunately, that help had to wait for a few years while family matters took their toll: There was financial trouble with Joseph’s bank, and then the unfortunate death of a daughter, Young Betsy Fry in November of 1815.

But by 1816, Elizabeth was back in action and started charity work for the women at Newgate Prison. She was able to place a chapel and start a system of supervision that required the women to take part in other duties, including sewing and, of course, required Bible studies. In 1817 she helped start the Association for the Improvement of Female Prisoners in Newgate, of which her brother-in-law, Tomas Buxton, himself a philanthropic person. He went on to publish a book, An Inquiry into Prison Discipline, which was about his discoveries of the squalid conditions in Newgate. The book did a lot to help Elizabeth’s cause to make conditions better there. It went through five editions in its first year alone, published in French and was distributed throughout the European continent.

Buxton was elected to Parliament and through his connections; Elizabeth was able to address The House of Commons in Westminster Palace. This is an influential group to have on one’s side, as the Prime Minister of England is answerable to the House of Commons and must support them. There, Elizabeth Fry gave testimony to the terrible conditions at Newgate Prison, telling of how the women had to sleep in spaces of only six feet by two feet, with up to 30 women in a room. She told them how the prisoners are mixed together without consideration of the types of crimes – hardened criminals with first time offenders of petty crimes awaiting their court dates.

While the House of Commons were moved by some of her testimony, perhaps Elizabeth should have tempered her words. Her religious zeal came through when she spoke of such thing as capital punishment being an “evil act”. Most Members of Parliament still thought that the system of capital punishment was justified, even though there were at least 200 offences for which one could be sentenced to death; one of those was passing a forged banknote.

It was February, 1817 when two ladies, Charlotte Newman and Mary Ann James were sentenced to death in Newgate Prison for forging banknotes. Elizabeth tried her best to convince the authorities to pardon the two prisoners, but her pleas fell on deaf ears. Then, on February 17, 1818, they were hanged as the bells of St. Speulchre’s rang out.

Soon after this Elizabeth tried to stay the execution of Harriet Skelton, a maidservant who had been found guilty of “uttering”, which was passing a forged banknote with intent to defraud. This time Elizabeth went as far as visiting the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth. Until the year 2005, when it was transferred to the Ministry of Justice, the Home Secretary was also in charge of prisons and probation. Lord Sidmouth told Elizabeth Fry that she what she was trying to do was dangerous because she was trying to “remove the dread of punishment in the criminal classes.” On April 24, 1818 Harriet was hanged as the church bells once again rang out in the morning.

The next Home Secretary, Sir Robert Peel, saw things a bit differently. Accepting the position in 1822, Sir Peel overhauled the legal system and repealed more than 250 outdated statutes. Because of his actions, the prisons started receiving visits from chaplains, and female prisoners were overseen by newly appointed female wardens.

One can imagine the happiness that Elizabeth Fry had when these changes were at last made, but she was not done. She took on more prisons throughout England and found that in many cities the conditions were the same as, if not worse than, Newgate. She helped publish a book “Prisons in Scotland and the North of England” listing the conditions that they found, demanding changes be made there as well.

Elizabeth continued on with her tireless efforts, including homelessness, workhouses, mental asylums, nursing, convict ships, etc. While on holiday with her family, Elizabeth was dismayed by the number of panhandlers in the streets. She therefore started the Brighton District Visiting Society, which was aimed at helping the poor. It was a success, and these societies soon took root in cities all over England. She continued on and on, advocating for kindness to others where she saw the need. She began a campaign for obtaining libraries for the solitary Coastguards and naval hospitals.

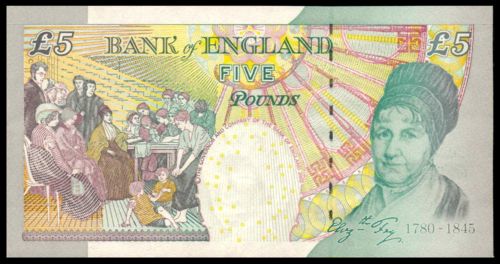

Elizabeth Fry died on October 12, 1845 from a stroke. After her death, there were many dedications of buildings, plaques, asylums, etc. in her honor. She is remembered too in Canada, where across the country there are Elizabeth Fry Societies that offer charitable assistance to women who have been incarcerated or are otherwise in legal troubles. Elizabeth Fry has also been depicted on the Bank of England’s 5 Pound Note.