ERITREA

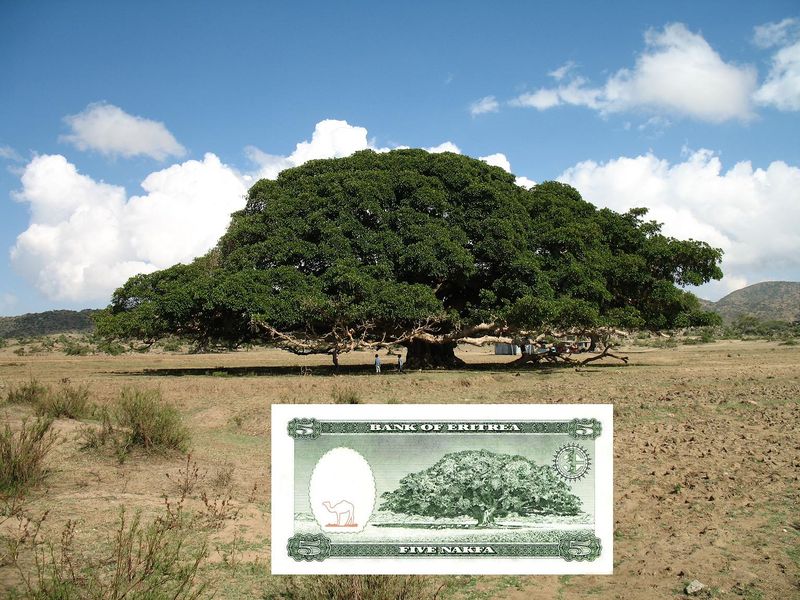

Eritrea: Sycamore Fig Tree

Of the many plants in this world, the trees are perhaps mankind’s greatest friend. And not just to us humans, either. While humans may be the only ones to be inspired to write a poem, many creatures benefit in some way from trees. Whether it be food, shelter or shade, without the trees the world would be a place I’d not care to imagine.

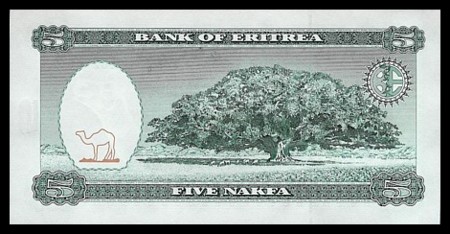

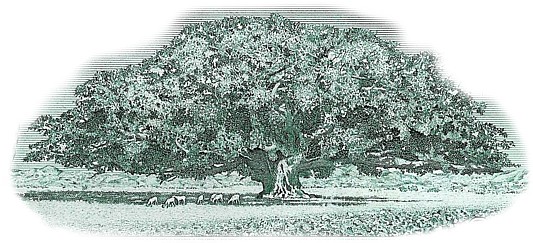

Some trees, depending on their location, have proven themselves particularly beneficial to the survival and comfort of humans, animals and insects for longer than we can remember. One such tree is the Sycamore Fig, with its grand canopy providing shade for all who come near. The shade is, however broad and cool, perhaps the least beneficial aspects of this magnificent tree. Known to the arborists as the Ficus Sycomorus, the Sycamore Fig is native to central Africa, but has been growing as far as Lebanon, and South Africa for millennia. It can be grown elsewhere, but it is in Africa and the Middle East that it is most common.

This wonderful tree is one that was mentioned no less than nine-times in the Holy Bible. It was beneath a Sycamore Fig in Matariya, located north of Cairo on the east side of the Nile River, where Jesus and his family stopped to take refuge in its shade. There, beneath the tree, Jesus created a well and drank from it, and bathed in its water. The same tree is still living, and is used to prepare what is called the Chrism, a tincture of oil and balsam used in sacramental ointment used for baptisms, confirmations and several other religious ceremonies. In the Gospel of Luke, the story of Zacchaeus is recounted as he climbed a sycamore for a better view of Jesus when he was in Jericho.

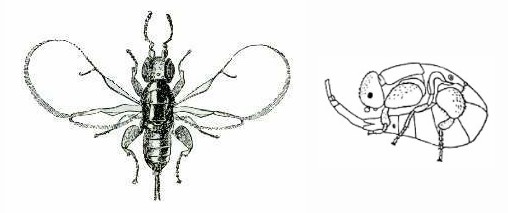

The tree is commonly found to be about 65 feet, or 20 meters, tall and has large oval-shaped leaves. The figs of this tree develop in clusters on small branches and are about 2-3 inches (20–50 mm) round with a yellow/reddish hue when ripe. The Sycamore Fig produces its fruit almost year round, and a great many animals and insects use the trees for their food. Insects, especially a species of wasp, have learned to use the fruit as a means of reproduction by laying an egg in s fig where they can develop.

But the wasp is not the only one to benefit from this relationship. The Sycamore Fig benefits as well, and in fact depends on the little fig-wasp entirely. The trees produce both male and female versions of the fig fruit, which are actually flowers that are enclosed within the fruits outer covering, so the wind and insects flitting from one to the other are unable to transfer the pollen to other fruits and trees.

However, the female parasitic wasp has learned to burrow into the figs to lay eggs. Importantly, the little wasp doesn’t seem to be able to tell the difference between the male and female figs, and will crawl inside either a male or a female fig with hopes of laying her eggs.

Should the wasp burrow into an inedible male fig, called a caprifig, she is able to lay eggs due to the particular arrangement of the interior, and will then die. When the wasps hatch, they leave the fig and the female will fly off to another fig, preferably in a different fig tree, and crawl into another fig to lay an egg.

When a wasp tunnels into a female fig the unlucky wasp finds she is unable to lay the eggs due to the fig’s anatomy being unsuitable for egg laying, and the wasp dies inside. However, the wasp has brought in all the pollen from the male fig it just left, and pollinates the new fig, which ripens and turns into an edible fruit. Yes the wasp has died inside, but you won’t be stung biting into the ripe fig as an enzyme in the female fig called ficin helps absorb the wasp and turn it into protein, and it becomes part of the fig itself.

The figs can be eaten raw or dried for later use. Additional uses include being made into various beverages such as teas, or fermented concoctions. Some people have used the fig leaves to help increase the milk output in cattle. In Egypt the bark is used for timber, and many mummies were found with coffins made from this tree. The wood of the Sycamore fig is soft and light-weight, and has long been used to make drums. The bark has been used as both a thin plank or stripped to make cords and ropes. Several medicinal tinctures have been made from the bark, latex, figs, and leaves for a wide variety of ailments including burns, tuberculosis, and dysentery.

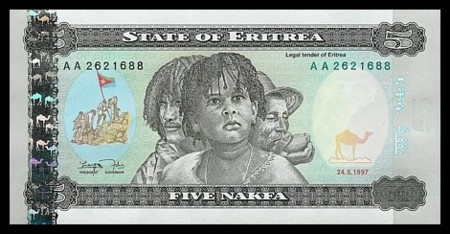

With such a variety of uses it is not surprising that the giant Sycamore Fig in Eritrea was placed on the 5 Nafka banknote in 1997, and continues there today. Not only is it a tree with roots that reach not just into the ground, but into the history of humanity throughout the ages.

In addition to the tree, Eritrea portrays a national symbol of its independence with the raising of the flag, and also pays homage to the different nationalities within the country, including the stages of life, a Young boy, young man, and older man.

The ancient city of Nafka played was an early victory in the Eritrean struggle for independence. Though the city was devastated, the Eritreans held onto the city and began rebuilding the area up. As it was such an important part of their independence movement, the banknotes bear the city’s name.

Collectors of Eritrean banknotes will know that there was a newer version of the banknotes issued in 2015, adding colorization and other small changes to the notes. This change was a secret operation that was primarily done to thwart Sudanese human traffickers who were using the Nafka as their operating currency in moving people into Europe. Due to the vast amount of human trafficking taking place, a huge amount of Eritrea’s money was held out of the country, and in keeping the currency change secret for as long as possible, the ability for the criminals to exchange the currency was severely limited. The replacement started on November 18th, 2015 and by January 01, 2016 the old banknotes were no longer redeemable. Restrictions on the amount of hard currency individuals could withdraw from banks per month have also kept the currency largely in country, though there have been issues with a lack of available currency within the markets.