GUINEA - BISSAU

Amilcar Cabral

Amilcar Lopes Cabral was born on September 12, 1924 to his father, Juvenal Cabral and mother, Iva Pinhel Evora in Bafata in Portuguese-Guinea (now Guinea-Bissau). His farther was a school teacher and Civil Rights activist, and his mother worked as a seamstress and in a fish packing plant. When his father inherited some land in Cape Verde, Amilcar moved to the islands with his family and spent the rest of his childhood and early school years there. Throughout his years in Cape Verde, he suffered, along with the rest of Cape Verdeans, through years of drought and famine that plagued the islands of Cape Verde. His time in both Cape Verde and in Portuguese-Guinea allowed him to have a dual allegiance to both of the Portuguese controlled countries.

After finishing his secondary education, he obtained a job in Praia, the capitol of Cape Verde in 1944. While working there, he also pursued a scholarship to study in Lisbon, Portugal. In 1945 Amilcar was granted a scholarship and left for Lisbon to study Agronomy, a science dealing with the growth and use of food, which was a main concern for him while a child in the drought stricken Cape Verde Islands.

While in Lisbon, Amilcar was able to learn much more than his studies on agronomy. The time spent in Lisbon allowed him to see that there were political and social issues that were plaguing the Cape Verde Islands as well as the drought and famine. He was able to form the ideas in his mind about how to help Cape Verde and its people to overcome their social, agrarian and political strife. Amilcar was beginning to grow rebellious to the Portuguese government’s role in Africa. On a return visit to Cape Verde, he tried to educate the people by broadcasting his ideas on the radio and by giving a class at a local school. But the Portuguese government soon became nervous about his actions and disallowed his broadcasts and classes. Frustrated, Amilcar then returned to Lisbon and resumed his studies.

Back in Lisbon his time was not spent entirely on agrarian studies. His previous term in Lisbon made him aware of the political state of his two nations, and his recent trouble with Portuguese authorities stopping his class and broadcasts made it even more apparent as to how bad it really was. He soon met and befriended several students who were from Portuguese controlled Africa. His new friends would gather with Amilcar and discuss important issues affecting Africa. They soon had an idea of re-Africanizing the identity of the people throughout Africa, and removing the yokes of colonialism from those nations who were still controlled by European countries.

Finishing his studies in Lisbon, Amilcar graduated from the Agronomy Institute in 1950 and worked as an apprentice in Santarem, Portugal for a couple years. But Amilcar still has plans to help the people in Portuguese Africa, and his time spent as an apprentice was coupled with an overall plan to return to Africa.

In 1952 he then accepted a job as an agricultural engineer in Portuguese-Guinea where he traveled the country and became more familiar with the landscape, and people of the country. Portuguese-Guinea was a strong strategic point for Portugal as it provided access to other Portuguese colonies in Africa. Yet Portuguese-Guinea was the poorest and least developed African Nation at the time. Now back in his native Portuguese-Guinea, Amilcar worked not only as an agronomy engineer, but also to plant the seeds of awareness and rebellion amongst the people. His work was soon noticed by the governor of Portuguese-Guinea and seen as a threat to the government, and Amilcar was forced to leave in 1955, being allowed to revisit only once a year to visit family.

Amilcar chose to go to Angola, another Portuguese colony, and there he worked again as an agricultural engineer. He also joined the MPLA (Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola) after meeting with several of its members. His time in Angola, and with the MPLA, undoubtedly taught him organizational skills and the effectiveness of an armed resistance. During one of his return visits to Portuguese-Guinea, he not only met with his brother, Luís, but also with Aristides Pereira, Júlio de Almeira, Fernando Fortes and Elisée Turpin. Together, Amilcar and these men organized the African Party for the Independence and Union of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC). The party’s initial goal was to gain independence peacefully from Portugal, but after the Portuguese forces killed 50 striking dock workers in the Port of Bissau’s Pidjiguiti docks in Portuguese-Guinea, PAIGC started to take a more militant stance starting with skirmishes in 1962, and ending up with Amilcar, the leader of PAIGC, declaring war on Portugal in 1963.

The PAIGC received military weaponry, tactical strategy, and medical support from several communist countries such as Cuba, the USSR, and China throughout its fight for independence. Portugal, under the rule of the dictator Antonio Salazar, had problems fighting its colonial wars with it’s colonies in Africa. Portugal, under Salazar, had long held that the African colonies were an integral part of Portugal and was willing to fight for them. Yet Portugal’s government underestimated the PAIGC and did not consider the organization to be a major threat like the MPLA in Angola. The Portuguese economy soon took a serious hit, with upward of 40 percent of Portugal’s budget being spent on the wars in Africa. The war was unpopular and was now entering the second decade with no end in sight. Under the leadership of Amilcar, the PAIGC was winning their battle for independence, but slowly. The Portuguese military was thinly spread throughout its African colonies at this time, fighting different factions, and by the time that they realized that the PAIGC had a strong hold in Portuguese-Guinea, the fight was nearly over.

On January 20, 1973, Amilcar was the subject of an attempted capture gone awry. Lead astray by his own people within the PAIGC, Amilcar was on a trip to the Republic of Guinea, under the idea that he was going to sign a treaty with Portugal to establish independence for Guinea and Cape Verde. A longtime rival in the PAIGC, Inocencio Kani had betrayed Amilcar and was working with other Portuguese spies in the PAIGC to assasinate Amilcar Cabral. Amilcar fought his assailants as they were trying to subdue him and in doing so was shot in the abdomen. He fell to the ground and was then shot in the head.

Despite the assassination of the PAIGC’s leader, Portugal did not gain any tactical or political advantages. Amilcar’s brother Louis Cabral took the helm of the PAIGC and the fighting was escalated. The PAIGC then received new ground to air missiles that removed the threat of Portuguese Aircraft. Without the Portuguese planes overhead, the PAIGC was able to greatly enhance their efforts and by September 24, 1973 PAIGC declared victory and independence for Portuguese-Guinea. Portuguese-Guinea was renamed Guinea-Bissau, adding the name of the Capital City, as the Republic of Guinea was already known simply as Guinea. Amilcar’s brother Luis became the first president of Guinea-Bissau.

On April 25, 1974 the Carnation Revolution took place in Portugal, replacing the dictatorship with a democratic government. This coup d’ etat was also successful in decolonizing Portuguese oversees colonies with the exception of Macau, which remained a colony until 1999.

After the Carnation Revolution in Portugal, the PAIGC became a major political force in Cape Verde, and they were able to broker a transitional government deal with Portugal in 1974, and on July 5, 1975, Cape Verde gained independence from Portugal

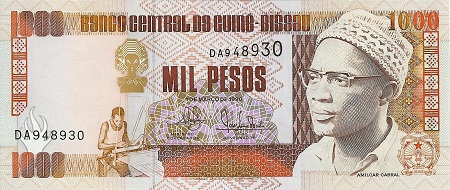

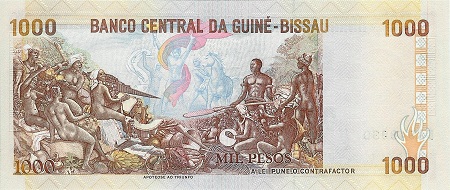

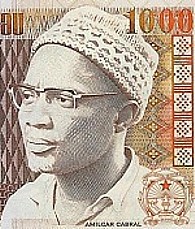

Amilcar Cabril was commemorated on this 1,000 peso banknote. The allegory on the reverse depicts the struggle for independence, and the phrase “Apoteose ao Triunfo” translates as “the Glory of Triumph.”