GUINEA

Ahmed Sekou Toure / Sande Mask

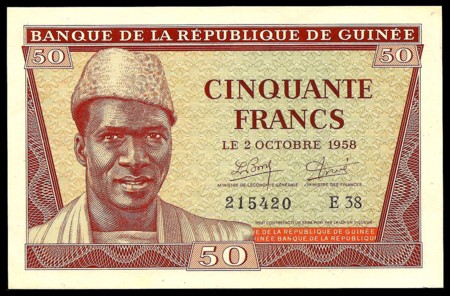

When the country of Guinea gained independence their first banknote issue included a 50 Franc banknote with a portrait Ahmed Sekou Toure, the first President, on the left side. Toure served as President continuously from 1958 until his death in 1984. His presidency, like so many in post-colonial nations, was marked by a radical change in policies, devolving into a dictatorship with the people suffering the oppressive policies.

Toure was working as a postal clerk in the early 1940’s, where he became motivated by a labor union movement. While there, he organized a labor strike which lasted 75 days. Later, no doubt as a result of his actions at the postal service, he became the Secretary-General of the Federation of Workers’ Unions in Guinea. He would later go on to become the Vice President of the World Federation of Trade Unions. An effective political speaker, Toure helped form the African Democratic Rally (ADR) in 1946. The ADR was political party which was instrumental in the fight for decolonizing French Africa.

In 1951 he was elected to the French National Assembly, but he was barred from taking his seat. He was re-elected to the same position in 1954, yet he was still not allowed to take part in the assembly. It was only after being elected as the mayor of Conakry, the capital of Guinea, in 1955 that he was allowed to take his elected seat in the assembly.

In 1958, French President Charles De Gaulle proposed to the French Colonies in Africa, that they should decide if they want to become part of a new Federal Community, or seek Independence. It is no surprise that, given Toure’s political history and treatment in the French National Assembly, he would lead the nation in seeking complete independence from France. Guinea soon became fully independent on October 2nd , 1958, with Toure serving as President.

France did not accept this outcome well, and pulled out all their civil servants, professional French civilians, and removed all equipment that could be moved. This drain on resources of course left Guinea in a bind, so in a bid to avoid immediate failure as an independent country, Toure asked for assistance from both Western and Communist countries. Due in part to the communist interest in Guinea, the United States became the chief supplier of aid and investment by 1961.

Toure would later lend his support to the independence of Guinea-Bissau (then Portuguese Guinea), which, on November 22nd, 1970, resulted in a military raid called Operation Green Sea, on Conakry with Portuguese Troops and Guineans opposed to Toure’s rule. The raid destroyed some ships and planes which were related to the Guinea-Bissau revolution, and freed some captives help in Conakry. The overall attempt at a coup d’état failed, however, and Toure remained in power.

Toure’s based his ruling style largely on the ideals of Karl Marx, and so he had all foreign companies nationalized, appropriated the funds and farmlands from local land owners, and suppressed the economy. He declared his political party the only legal party, which ensured his continued re-election. He was accused by his opponents of tyrannical behavior and many of those who opposed him were tortured and killed.

In answer to his lack of real democracy, failed economy and brutal policies, he said: “Guinea prefers poverty in freedom to riches in slavery.” Even so, that did not stop his imprisoning his opponents in concentration camps, where it is estimated that up to 50,000 people were killed, mostly through starvation, and were buried in mass graves. In the 1980’s it was estimated that most Guinean’s lived on the equivalent of only $140 US Dollars a year (38 cents a day), and had only a 10% literacy rate.

Toure travelled to Saudi Arabia in 1984 to seek a resolution for a dispute between Morocco and the Polisario Guerillas over Western Sahara. While in Saudi Arabia, Toure suffered a heart attack. He was transported to a heart clinic in Cleveland, Ohio, but died while in hospital on March 26th, 1984. Ahmed Sekou Toure had ruled Guinea for 25 Years, 176 Days.

After his death, the military seized power with Colonel Lansana Conte declaring an end to Toure’s “bloody and ruthless dictatorship.” They disbanded Toure’s political party, closed his National Assembly, freed 1,000 political prisoners, and executed several of Toure’s close political associates, including those who ran the concentration camps. In a 2015 estimate, Guinea’s life expectancy had risen to 58 years with a literacy rate of approximately 30%.

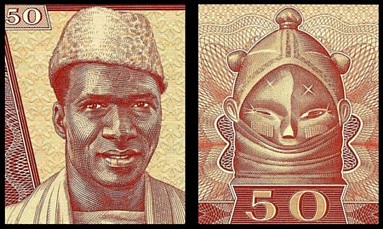

On the back of this Guinea 50 Francs Banknote from 1958 there is a striking vignette of an African Tribal Mask, whose beauty and strangeness is immediately captivating. Right away it seems apparent that his is more than the typical mask one often sees in the western world, mostly flat boards with a face carved into it. This mask is obviously to be worn and seems almost magical, as if, instead of merely representing the object the mask is carved to be, the wearer would actually embody the mask, becoming one with its denoted qualities.

Throughout Africa there is to be found a mix of tribes whose lineage and heritage are not to be wholly confined by national borders, too often arbitrated by the colonial powers without regard to those who lived there. Such is the case with Guinea, once part of French West Africa, with over two dozen traditional ethnicities.

The Mende people are one of these ethnic groups, and they have a history of living in small villages separated by only a couple miles from each other. Found throughout the Central West Atlantic areas of Africa, they have traditionally been an agrarian culture cultivating their lands manually with only hand tools. Their work is, like most societies, separated between the genders, with men performing the heavy labor of cultivating land, planting and harvesting. Women are usually found cleaning and preparing the harvested foods, of which rice is a primary staple in many Mende villages.

Mende society can be polygamous with a senior male the head of the household, and whose job it is to maintain morality and obedience, as well as managing the household finances.

Further divided by gender are two schools: the Poro, for men, and the Sande, for women. Some people have referred to these as secret societies, but in fact, they are open to all in their communities. In order to be considered sensible, well-rounded adults, all Mende adolescents need to be initiated by their respective societies.

The mask shown on the back of this banknote is called a Sowei (also known as Bundu) helmet mask which is part of the Sande ritual for teaching young women to become civic minded and productive members of the Mende society.

After the harvest season the adolescent girls are taken away from their villages to a section of cleared land where they are initiated into the Sande Society. They are kept there for a period of time that depends on their age, social standing, and their ability to adapt. Though thought of as barbaric in most of the world, they still practice genital mutilation, and it is during this initiation that this would be performed on the unfortunate victim.

After the girls have had time to recover from their mutilations, they are then instructed in various skills. While farming, dancing, cleaning, etc. are nothing new, but their training encompasses not just the work, but the manner in which the work is performed. After their initiations, the girls will be expected to work as an adult, a wife, and as a mother. Aspects of how to get along in a polygamous marriage are also imparted, along with how to behave among their future husbands relatives.

Though women have often played roles as in religious ceremonies and acted as intermediaries between spirits and the living, the Sande Society is the only instance where a mask is worn solely by women. They are carved from the trunk of a tree and weigh about four pounds. The mask is typically worn by the senior woman of the Sande Society, along with a cotton coat fully covered in a thick mass of long black raffia fibers or twigs attached all the way to the neck. This figure appears at key moments during the girls’ initiation period, announcing when they have passed important parts of the ritual, and to request food to be prepared to take back to the girls. At the end of the initiation, the girls are ritually cleansed, dressed and often covered in white clay. As they are returned to the village, they are presented as marriageable women. A final celebration includes the masked figure in a dance of up to two hours in length.

Sande masks are well known for their unique beauty and allure. These masks are used in the initiation of young women into their society, where they learn aspects of their traditional views of the Mende. The masks are carved by men who take care to carve them using the same care as a woman would take with their own personal appearance. They are smoothed with leaves of the Fichus Tree, and darkened with the tannin from various other leaves. Before use the masks are coated with Palm Oil to bring a shine to the mask. Most if not all girls are expected to take part of the Sande society by the time they reach puberty.

The masks are all black with female faces depicting the traditional concepts of beauty among the Mende peoples. The designs adhere to traditionally symbolic ascetic features. There are neck rings that feature prominently on these masks, which at first appear maybe to be a wrap but, as the Sowei is said to represent a water spirit, these rings represent the water ripples as the water spirit rises out of the waters. The masks are polished to represent healthy, shiny skin, with stylized hair. The hair styles vary greatly and have been used to date older masks due to the changing popularity of hair styles.

Most masks have one face, but there are masks with two, three and, though not common, even four faces. When the woman dances with a Sowei mask, the costume preparation is taken seriously and with great care, leaving only the thin slits open for the dancer to see through, and the raffia covering completely obscuring the body. This is done so that the Sowei spirit does not come into contact with the dancer as she embodies the spirit.

Some of the distinguishing features of a Sowei Masks and their meanings:

Elaborate Hair – The hairs styles are largest and most elaborate aspect of the mask. They are finely carved, and can be separated into different rows varying in number, from front towards the back of the head. There are often nobs or buns that are at the crown and ends of rows. The perfection of the hair style shows the divine nature of the Sowei’s world in contrast the rough natural world depicted by the raffia fibers.

High Brow/Forehead – This denotes intelligence, happiness and self-confidence. The forehead is never concealed by hair.

Lowered Eyes – These indicate a sense of modesty. Eyes on the masks will have thin slits for the wearer to see out of. Sometimes these slits are cut into the neck area where they are not as easily noticed by the observer.

Oversized Eyes – Large eyes evoke a sense of knowledge.

Shiny Black Color – These qualities show healthy skin, and impart a sense of mystery.

Neck Rings – Healthiness and prosperity are represented by the neck rings. These rings often cover the chin. The rings are the same width as the masks head, allowing for it to fit over the wearers head. These rings signify the water ripples emanating from the head of the Sowei as the spirit exits the water.

Cowry Shells – Used in the past as money, these shells are a show of wealth and prosperity.

Fish/Water Creatures – Such items represent the water home of the Sowei spirit.

Animal Horns – When used, these represent medicinal properties and skills in healing.

Cooking Pot with 3 Legs – Pots and other such items are signs of domesticity.

Small face – Small faces, sometimes with two or more faces are signs of beauty to the Mende. On the masks, a small mouth, usually closed, signifies silence and composure. The faces are confined to the lower half of the head, conforming to the Mende ideals of beauty and feminism. The nose is also small and delicate.

Scarification – Denotes beauty and passage through the initiation. Usually a few vertical lines under the eyes, ‘X’ shapes near the eyes and forehead.

Holes pierced in the bottom of the mask – Likely placed for ventilation for the wearer.