Lithuania

Northern Mole Lighthouse

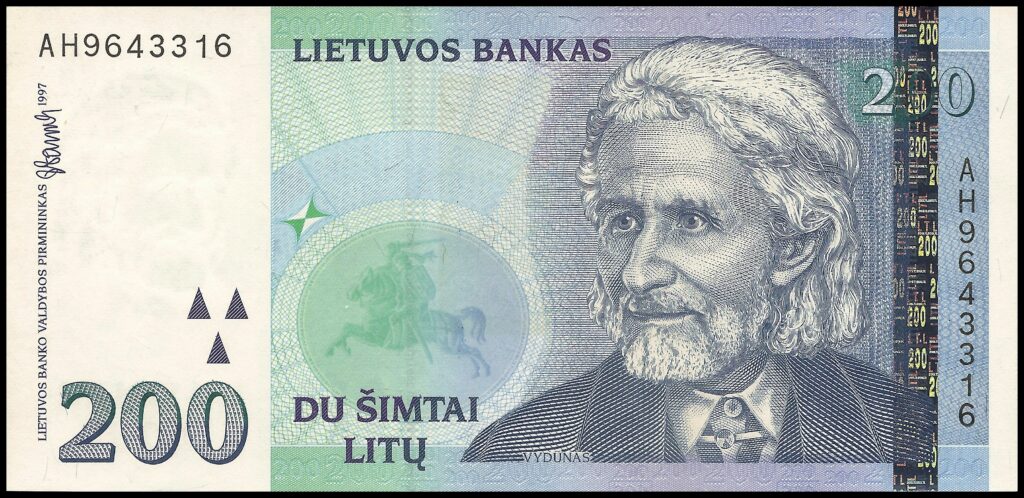

200 Litu issued 1997

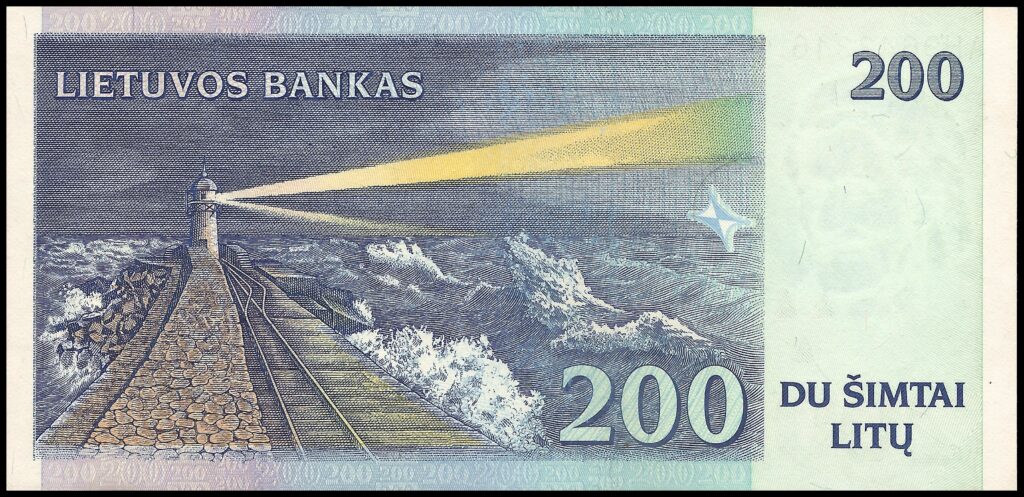

Northern Mole Lighthouse on Lithuania’s 200 Litu Banknote shows the beacons of light casting its rays of hope to seafarers in the deep of night, allowing them to know their position and to guide them safely to their destination. The lighthouse got it’s name from the constructed harbor mole, a breakwater that was installed for the light itself and for the loading and unloading of ships.

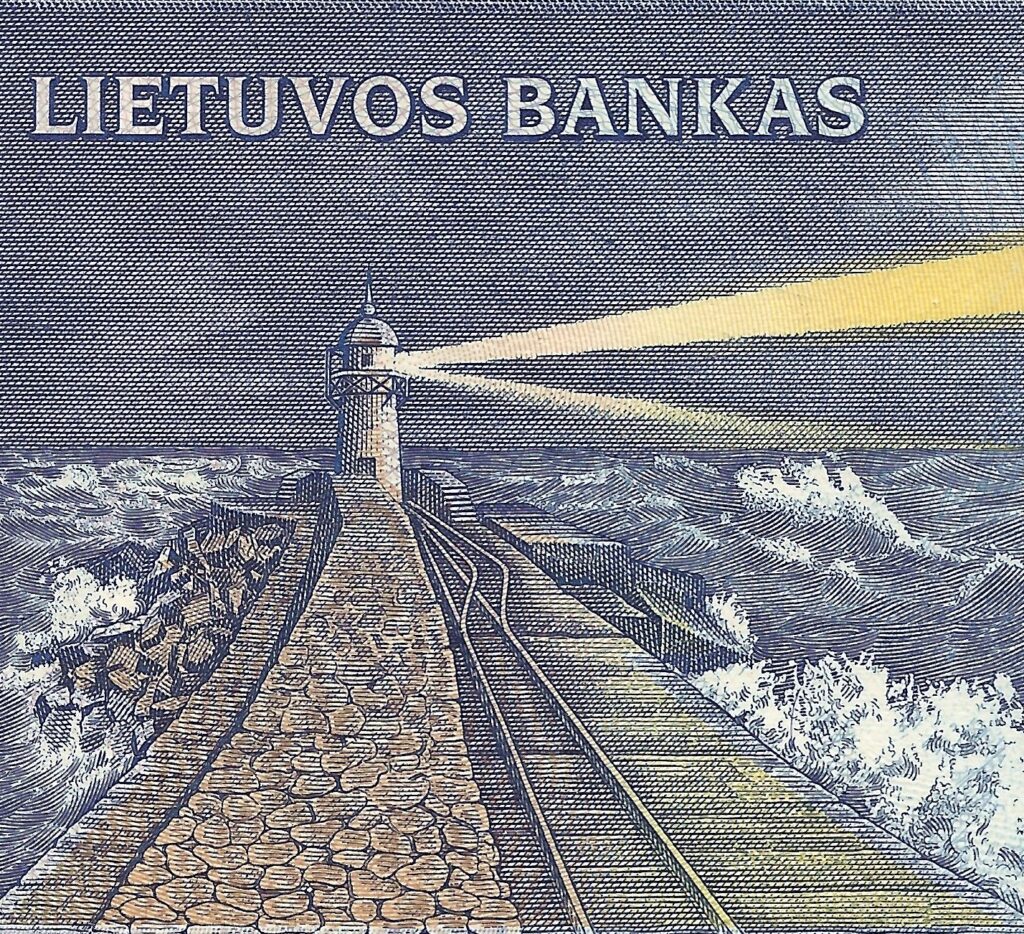

Construction began as early as 1834, but it was a long time before it saw any service. The first part of construction was to build a 3,084 foot (940 meter) concrete and stone quay, which is a platform extending into the water for loading and unloading ships, which was completed 24 years later in 1858. Then an 8-foot (2.5 Meters) wide pier that was 6.5 feet (2 meters) high which further pushed out into the water another 1,509 feet (460 meters) was built. The project was finally completed in 1884 – a full 50 years later – when it was again extended 2,150 feet (7053.806 meters) with the Northern Mole Lighthouse at its end, standing about 30-feet (9 meters) high. The lighthouse was first known as the White Lighthouse as it was painted white and cast out a red light when it first started.

The mole, or pier/quay, whichever you prefer to call it, was equipped with a narrow gauge rail-lines for transporting materials and supplies to the light as well as to service the rest of the mole, and can be seen depicted on the banknote image as well. Much later on, in 1931, a fog-horn was installed at the light, sounding in hazardous foggy conditions for 3-seconds on, ½ second pause, 3-seconds on and a 22 second pause, then repeating.

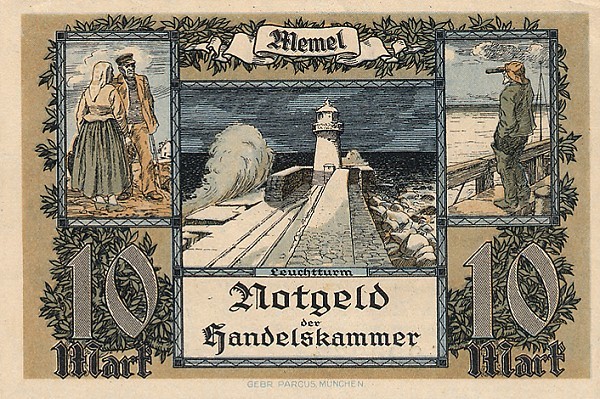

The Lighthouse has been commemorated on two banknotes, the Lithuania 200 Litu (P-63) issued in 1997, and the Memel 10 Marks (P-5) issued in 1922 which more resembles notgeld than a regular banknote.

If you’re wondering why Memel would issue a banknote with a Lithuanian lighthouse on it, the answer is that Klaipeda wasn’t always Klaipeda and it wasn’t always in Lithuania. The port in Klaipeda has long been valued as a fishing and shipping port at the end of the Nemunas River. The region’s valued geographic area has meant that Lithuania has been under the control of other countries in it’s past, including German/Prussian forces, Polish administration, Nazis and Soviet Communist governments.

In the year 1252, Teutonic Knights took control of the area and built a fortress and called the city Memelburg, which was later shortened to Memel. There were three instances of other names used throughout history: a letter in 1413 calling it Caloypede, a surviving legal document from 1420 referred to it as Klawppeda, and again in 1422 the treaty of Meino called it Cleupeda. Other than those instances, Memelburg and Memel was the name actually used until 1923.

Politics of the region and era caused a name change from 1923-1939 when Klaipeda and Memel were both officially used by the Lithuanian government once the Treaty of Versailles separated it from Germany after WWI. This did not last long, as during WWII, Germany again took control of the city and renamed it Memel. Once WWII ended, the city returned to Klaipeda and has not changed since.

The loss of Klaipeda in WWII was significant to Lithuania. About 75% of foreign trade for Lithuania passed though Klaipeda/Memel, most of which was now lost to the German war effort, causing Lithuania a loss of 30% or more if it’s industry. Once the Germans were ousted by the Soviet army in 1944, Lithuania was incorporated into the Soviet Union, continuing to suffer under that regime as well, lasting until the fall of the Iron Curtain. It has been estimated that there were over 780,000 lives lost to the actions of the German Nazi and Communist Soviet occupations.

The Lighthouse shines no more. It, along with many other lighthouses and buildings, was destroyed during the military action in WWII. A small, automated light has since replaced it. And though the North Mole light will shine no more, after WWII, the Lithuanian people have begun to shine themselves like they have rarely been able to do in their troubled past.

The portrait of the Lithuanian 200 Litu Note has a portrait of Vilhemes Storosta, aka Vydunas, who was a philosopher, poet and musician.