MEXICO – YUCATAN

The Boom and Bust of Mexico’s

‘Green Gold’ in the Yucatan

When the Spanish were in control of Mexico, there was a caste system in which the Spaniards were at the top, then the locals of Spanish descent, thirdly, the Mestizos who were of European and Indigenous heritage, and lastly the indigenous peoples, called Indios, which included the Maya living in the Yucatan. When Mexico won independence from Spain in 1821, the Spaniards were no longer in control, but the caste system remained, and the elite who were now in control of the political and economic issues of the Yucatan continued the caste system and exercised strict control over the lower castes, continuing to exploit their labors.

Immediately after Mexico gained independence, the Yucatan was originally still a part of the Spanish government, but as the next couple of years passed, the Yucatan was able to wrest itself from their political alignment with Spain, and in May of 1923 the Yucatan became its own nation. This lasted only seven months, however, as the Yucatan peninsula joined with Mexico on December 23, 1823, but with the stipulation that: “The union of Yucatan is that of a Federated Republic, and not otherwise, and therefore entitled to form their particular Constitution and establish the laws that it deems necessary…” In a federated government, the authorities of the state government cannot be taken back by the central government, and those in political power in the Yucatan wanted to be more of an independent state, while enjoying the benefits of being part of a larger nation. The geographic isolation of the Yucatan peninsula had kept them from much of the control of the governing parties previously, and they wanted to keep it that way.

Yucatan’s special status within Mexico was not well liked by all, and on February 21, 1844, the conditions that were granted to Yucatan on its absorption into Mexico were ruled unconstitutional, and in 1845 the government revoked their unique rights. On January 1st, 1846, Yucatan decided it was better to be on their own, and declared itself independent.

The Mexican-American War began that year, and the U.S. blockaded ships from Mexico, which stopped the Yucatan from trading as well, as the U.S. considered Yucatan to still be a part of Mexico. There were some talks between the U.S. and the Yucatan government, and there was a proposal that the U.S. would annex the Yucatan, which was even passed by the U.S. House of Representatives. This proposal was dismissed by the U.S. Senate however, as the war had become increasingly more complicated and annexing the Yucatan would likely be even more problematic and extend the war with Mexico.

Meanwhile the Indios were becoming more and more discontent with their position at the bottom of the caste level. They were constantly being used as the major source of labor, being mistreated physically and cheated in pay. Further, they were losing their lands to the elite who were enlarging their own plantations for the ever increasing production of henequen.

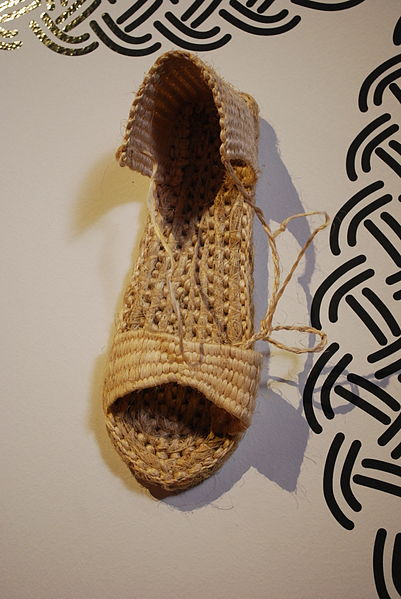

Henequen is an agave succulent of the asparagus family native to southern Mexico and Guatemala, and is very similar to the Sisal plant, of the same family. The leaves of these plants are fibrous and, though labor intensive, they can be made into twine, rope, clothing, bags, shoes, etc. Twine was favored for use in harvesting crops such as hay, as they are a natural fiber that can be easily consumed by cattle, unlike the plastic ropes or metal bands, which will harm the animals. The material is similar to the manila rope from the Philippines, famous for the large ropes, called hawsers that have long been used on sea-going ships. Manila rope is made from the abaca plant, of the banana family native to the Philippine Islands. An unfortunate aspect of manila rope is that grasshoppers are quite fond of the material at mealtime, while they do not find henequen appetizing at all.

Though henequen is related to the agave used in the production of tequila, henequen itself is not suitable for making the popular liquor. While the plant is capable of producing alcohol, the blue agave plant yields a much better flavor for tequila. Plus in the 1970’s the Mexican government made a law regulating that tequila could only be made within Jalisco state. That said, there is an alcoholic drink called licor del henequen, which has been recently marketed to compete with tequila. The licor del henequen is actually a type of mescal, or mezcal, and is not a true tequila. Recent studies on the henequen alcohol production are favorable for other uses in the food and chemical industries, which may prove to be a reliable future use of the plants after the fiber harvesting has been depleted.

As the henequen plantations continued to grow, they took more and more land for henequen and also for sugar production. Lands used for food production by the Maya were taken from them and those Maya who worked on the henequen plantations were used almost as slave labor. As the production of henequen increased, the demand for workers rose as well. With their land disappearing, and their labors being exploited, The Mayan Indios then took a cue from the Mexican and Yucatan independence efforts and made a bid to obtain their independence, or at the very least, rise from the bottom of the caste system.

In 1847 the Maya began revolting with the weapons that were given to them during the Yucatan bid for independence, and what became known as the Caste War began. Many skirmishes were fought with the Maya, and by 1848 the Maya forces eventually held most of the Yucatán, with the exception of the cities of Campeche and Mérida, built by the Spanish with encircling walls which held the Maya from entering. Eventually, the Yucatan government had to appeal to the Mexican government for assistance in dealing with the Maya Caste War. Mexico obliged, and in August 1848, the Yucatan was allowed to rejoin Mexico, and with their original agreement intact. The Caste War would officially last until 1901, when the war was officially declared over, but small sporadic skirmishes continued as late as 1933.

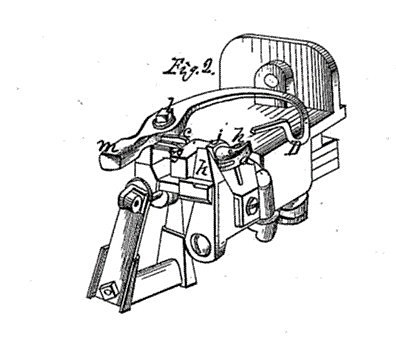

In 1857 a Wisconsin man by the name of John Appleby developed a small machine called a twine binder. This revolutionary machine made it possible to tie knots in the twine automatically. When attached to harvesting apparatus it became possible to use twine instead of wire to bale hay, grain and other crops. While wire baling was a well-established use, it was not only more difficult and time consuming, but cows would often ingest small pieces of the wire and become injured, and could even perish, from swallowing the metal wire. When this small invention was eventually manufactured in the later 1800’s a huge demand for more twine soon followed, and a world-wide search to find a good, cheap supplier of twine, or the materials with which to make twine, was underway.

The question of where to get the twine at low cost and in large quantities was met with many contenders. Flax and hemp were too costly and weren’t durable enough. Jute was also an option, but as it was imported from Asia, the shipping costs and delivery times were a concern. Manila rope and twine was a top contender as well, but it was prone to being eaten by grasshoppers. Similar to manila was the henequen fiber which was nearly as strong as manila fiber, and was not prone to be consumed by insects. As it was grown in the nearby Yucatan state of Mexico, its proximity to the United States also ensured that the shipping would be both affordable and reliable, making it the only viable choice.

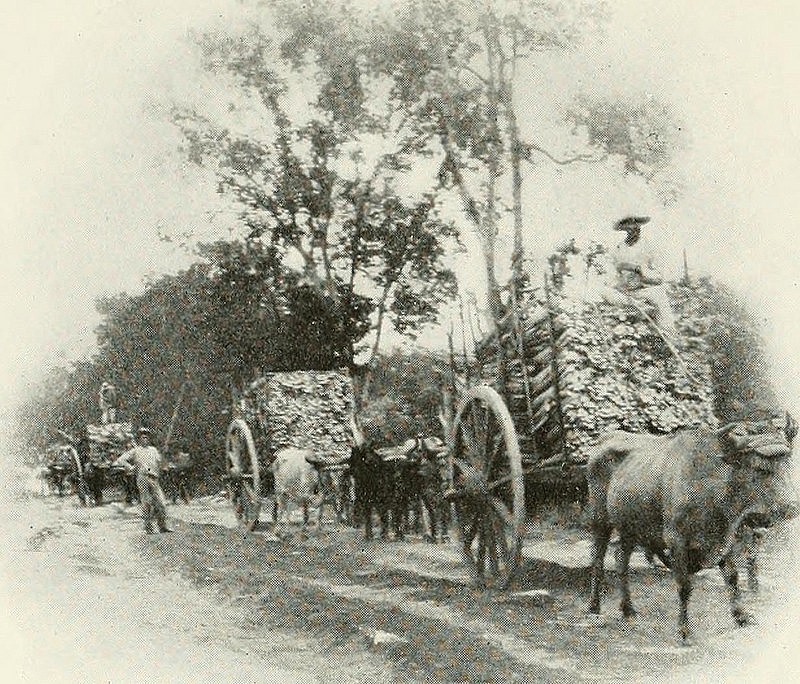

After the political issues with their separations from Mexico, the trade stalling from the blockade during the Mexican-American War, and the regional Cast War in the Yucatan, the demand made by the invention of the twine-binder was welcome news for the Yucatan. Their plantations were able to supply nearly all the henequen raw material for twine to the United States and to other countries as well. The demand and price for henequen brought incredible wealth to the region, and several hundred family farms were soon thrust into the realm of wealthy plantation owners, and a new class of people was created, the Casta Divina (the divine caste) who not only made money, but spent it as well.

Henequen was always a very valuable crop and was used by indigenous peoples long before European settlers. Those who were fortunate enough to own land after Spain’s conquest of Mexico were able to reap the benefits. Unfortunately, those benefits were increased by the mistreatment of the laborers that the plantations employed. While the plant has been used since pre-Columbian times to make fiber, it wasn’t until the 19th century that it was harvested in such large quantities that factories were required to produce enough materials for export. The product was so successful that by the 1880’s the Mexican state of Yucatan had become one of the most prosperous areas in the country, all thanks to the twine binder and the henequen plant that was nicknamed ‘Green Gold’.

The pueblo of Merida, located in the northwest part of the Yucatan, was transformed from a small, dirty pueblo to a modern city with paved streets, electricity, sewer system, telephones and railroads. Towards the end of the 1800’s the Yucatan had more railroad lines than anywhere else in Mexico, and the city of Merida was home to more millionaires than any other city in the entire world. It is odd, that given all this wealth that there were no banks in the area until 1883. This meant that despite the wealthy landowners having regional control, the real control was with foreign companies in the United States which was financing the endeavor. That control from several companies would quickly merge into one company: International Harvester.

Unfortunately the Caste War in the Yucatan was devastating, and at least one-third of the population died as a result, leaving the area with little to offer for labor. The plantation owners now had to start importing their labor, and they brought in workers from as far away as Korea, China and even the Canary Islands. Other workers were brought in from other parts of Mexico, including the Yaqui Indians from the Mexican state of Sonora. The treatment of the Yaqui’s was abysmal. They were sold throughout Mexico to plantation owners for 60 pesos, most of them to the henequen plantations. They were treated as slaves, not given enough food, and beaten. In addition, the Yucatan climate was very difficult for the Yaqui, who were used to the arid desert and grasslands, not the humid flatlands of the Yucatan peninsula. It is reported that two-thirds of the Yaqui laborers brought in for henequen production died within the first year.

Henequen harvesting must wait four years after planting for the plants to mature enough, but it continues for 20 years, after which the plant begins to decrease the leaf size. Harvesting begins by cutting off 3 to 5 leaves off each plant (cutting off more leaves will harm or kill the plant), which are bound together in small bundles and taken to the factory where they are processed by machines to separate the leaves and extract the fibers. At the factory, the fibers are then further shredded and separated, and are subjected to further refining which eventually separates them into distinct strands. From there, they can be processed into various sizes of small cords from twine to large diameter ropes.

International Harvester, and the companies that merged into it, had cornered the monopoly for binding twine supplied to the United States. The Comision Reguladora del Mercado de Henequen was originally a group of five persons set up by the Governor of Yucatan for the purpose of buying and selling henequen and providing a stable price to the planters. During the Mexican Revolution, General Alvarado took possession of the government and set himself up as a dictator in the state. He reorganized the Comision Reguladora and enabled them to obtain a monopoly over the purchase and export of henequen. Alvarado ordered the twine producers to sell their product at four cents a pound, U.S., and if there was anything left over after the product was sold and exported, it would be returned to the planters. It was further planned to make these payments to the planters in advance.

In order to be able to accommodate these changes, it was deemed necessary to have a large surplus to make these payments. An association with bankers in New York and New Orleans resulted in the Pan American Commission Corporation, which furnished the Comision Reguladora with a $10, 000, 000.00 capital. This sleight of hand in money management resulted in the increase of the reported cost of raw materials from 3 cents to 7.5 cents a pound, and by the autumn of 1916, twine was up to 14.5 cents a pound: a 300% increase in less than 2 years. Americans, who were used to getting the twine at 6.5 cents a pound before the Comision Reguladora, were feeling the pinch.

The U.S. Congress initiated an investigation, which resulted in a suit against the Comision Reguladora del Mercado de Henequen and the Pan American Commission Corporation for violating Anti-Trust laws in the United States. Meanwhile the price went to 16.5 cents per pound. The investigation found that the Comision Reguladora, while claiming to be a farmer’s cooperative, was in fact an agency of a military and despotic government that has been imposed on the people in the Yucatan. Further, it found that, in spite of claims to help the planters and industry workers, there had not been so much as one dollar distributed to them. The report stated that men who had worked for over 30 years in the industry reported that the price of the raw product was still at 3 cents per pound. The Comision Reguladora then offered a claim that they also had to pay higher wages to their employees. Investigation into this aspect revealed this to be another false claim. The workers were being paid in what the report called ‘almost valueless’ paper money that, when converted to gold, was the same amount as they were being paid before the Comision Reguladora was created.

The report further stated that the Trade Commission looked into the orders placed for bales of twine and discovered through the records that there was in fact a surplus of twine, not the shortage that was reported by the Comision Reguladora when questioned the previous year. The congressional record further went on to state that “This is the most dangerous attempt at monopoly and to increase the cost of living that has ever been conceived”. The result was that in 1916 alone, the sum being fleeced was $34,500,000.00. The Comision Reguladora’s claim that they were a governmental organization and should be exempt from indictment was denied because it was financed by U.S. bankers. Still, the ability to bring a meaningful suit against the Comision Reguladora would not necessarily be an easy one to enforce, due to its being overseas. Other ways were thus sought out to punish the Comision Reguladora.

Despite its scheming, the policies enacted by the Comision Reguladora were not achieving the desired outcome of a great empire of henequen plantations supplying henequen forever to the world. Because there were little monies being invested back into the plantations, there eventually was a decline in production, and some customers started buying elsewhere. On top of that, the U.S. Government schemed a little on its own and in 1918, in coordination with the cordage industry in the U.S., purchased far more bales of henequen than were needed. As a result, this stockpile served throughout the next year as well, leaving the Comision Reguladora with no orders from the United States for 1919. With the support of the U.S., the cordage industry spread rumors to the farmers and twine makers in the U.S. about the socialistic practices of the Comision Reguladora. With these rumors spreading in conjunction with the depressed economy after World War I and the increased suppliers from other locations, the Comision Reguladora, and the Pan American Corporation dissolved. This was the beginning of the end for the henequen trade in supplying material to twine makers.

International Harvester itself was unharmed and continued to survive for many decades, making some of the world’s best tractors and large trucks. In 1910, shortly before the fall of the Comision Reduladora and the Pan American Corporation, International Harvester controlled an amazing amount of the agriculture related industry in the U.S., including 85% of the harvester industry, 90% of the grain binding industry, 75% of the mower related industry, and at least 30% of all the other agriculture-related machinery industry. In 1916, International Harvester began to market its tractors, and by 1919 their famous McCormick Farmall tractor was launched, which effectively industrialized agriculture within the United States.

At its peak, it is reported that the Yucatan supplied about 90% of the rope used throughout the world. Production of the plant was at its highest in the early 1900’s, but the Mexican revolution, which lasted roughly from 1910 until 1920, caused a decrease in the production of henequen, and many other materials. Around that time combine harvester-threshers also appeared, and their adoption would eventually remove any need for binder twine. While demand for the product increased slightly during the World War II years, that era also saw the introduction of polymers which soon became cheaper to produce. As a result, the polymer materials steadily began to replace natural fibers. When the production of man-made materials really began to take off during the 1960’s, henequen production dropped again, and by the year 2000, it was down by 80%. Factories closed and plantations were abandoned throughout this time, leaving the Yucatan today with one of the more depressed economies in Mexico. According to the National Institute of Statistics and Geography, it is ranked 24th out of the 32 Mexican states.

Henequen is still harvested today, but it is only a faint shadow of its former glory. Tourism of the old haciendas have a small business, but most goes toward making fibers for baskets, sandals and clothing. The mescal type liquor made from henequen was marketed in 2003, but has not taken off as hoped and is still more of a regional drink. Henequen farming is still viable, but the practices of the past still haunt the product, especially in regional memories.

Who could have thought that something so simple as a piece of twine to tie sheaves of grain would have had such an effect as this.

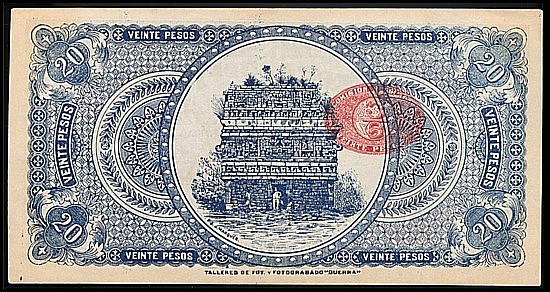

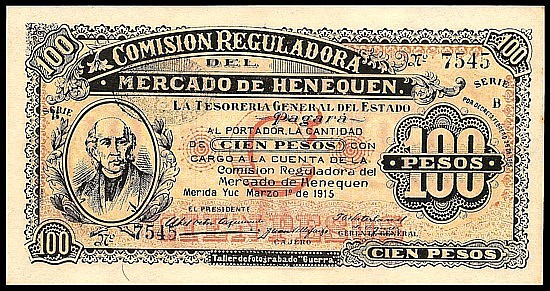

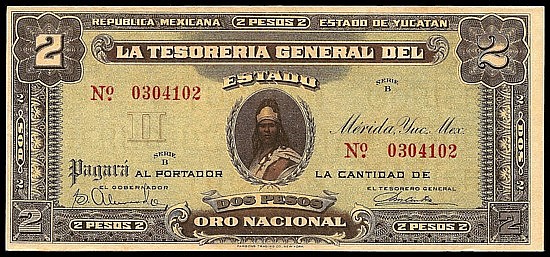

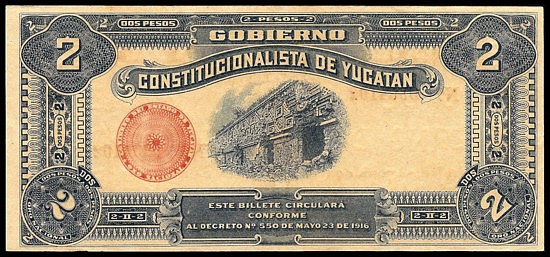

During their heyday, haciendas were operated without regard to the rest of the Mexico, and some issued their own currencies. The banknote below was issued by the Comision Reguladora del Mercado de Henequen, or CRMH. This was not a banknote backed by the Mexican government and would have been used as a type of local or company scrip instead of actual legal tender. The quality of the printing is of a much lesser quality, and is similar to that of other local scrip issued during the Mexican revolutionary period.

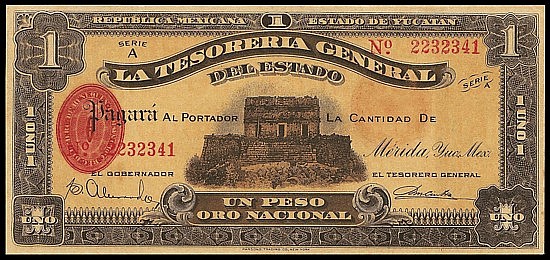

Rather than the massive pyramid at Chichen Itza, the banknote shows the Mayan ruin Casa Colorada, or Red House, located within the Chichen Itza site. It was named for the red paint that covered the walls if its rooms. Though mostly gone now, there is still some red flakes remaining on the walls. The Mayan name for this is Chichen chob, which the June 1914 edition of National Geographic called ‘The Prison’. It is now thought to have been a house for the elite. This is one of the best preserved buildings in the site, which is richly decorated with hieroglyphic carvings which annotate the date which corresponds to 869 AD and describe blood and fire ceremonies. The building sits atop an elevated structure with at least eleven crumbling steps to the top, which is 16 feet high. The building has three masks of the rain-god Cha’ak at the rooftop.

Cha’ak was a Mayan rain god who was often depicted with a thunder axe, and has a distinctive upward curved nose. To appeal to Cha’ak for rain, it was common to burn balls of rubber called ‘pom’. As the smoke from the offering of burned rubber rose it would gain the attention of Cha’ak who would send his emissaries with magical water in pitchers, which they would pour though the clouds, creating rain.

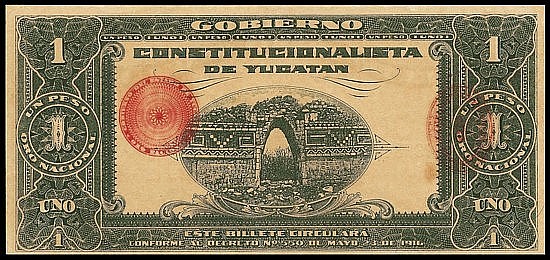

The ruins at Labna, located 1.5 hours south of the city of Merida in the Yucatan Peninsula, offer many artistic depictions of the Mayan rain-god, Cha’ak. This Maya ruin has been dated between 600-900 AD. Leading up to the ruin is the Sacbe, or White Road, which is elevated about four feet from the rest of the ground. The white road runs through the center of the site.

The portal serves as a passageway between two courtyards, which are thought to have been used for ceremonies. A ruined pyramid is at the end of one of the plazas. The portal rests on a base that is 4 feet high, 42 feet long and 13 feet high. The geometric designs on the Eastern side, depict a stylized Cha’ak mask on the North and South sides. Below this is a stylized zig-zag serpent. Though a smaller site, there are estimates that there were as many as 3,000 people living at Labna during its inhabitance. Labna has been translated from the Maya language to mean ‘Old Houses’. It was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.

Sources:

www.mexicomike.com

www.mayasites.com/labna

chichenitzaruins.org chichenitzaruins.org/places

coinfactswiki.com

www.redalyc.org

www.community.intelligentfanatics.com

www.inegi.org.mx

ambergriscaye.com

www.youtube.com/watch?v=tX6bwB-13QE

www.georgefery.com/labna-late-maya-classic

www.theyucatantimes.com

Man, Myth and Magic volume 13, 1970, P.1772

Congressional Record of the proceedings and debates of the United States Congress, Volume 54, Part 5 – 1917