NEW JERSEY COLONY

Isaac Colins

Isaac Collins was born on February 16, 1746 in Centerville, Delaware. His father, Charles, was a wine cooper in Bristol, England but left the trade to become a farmer in the colonies. His mother was Sarah Hammond and he had one sister, Elizabeth. By 1760, both his mother and father had died, and Isaac and Elizabeth became wards of his mother’s brother, John Hammond.

Soon after he was sent to live with his uncle John, Isaac was indentured as an apprentice to a printing shop, under Master Printer James Adams. James Adams had previously worked many years at the printers Hall and Sellers (who printed banknotes among other things) but had his own shop since 1753. Adams set up the first print shop in Delaware.

Isaacs’s apprenticeship was not just to learn about printing but also to serve the needs of the household he was indentured to as well. This included assisting in housework and preparing the meals. While working for James Adams, he learned much of his printing techniques, and was involved in printing the Wilmington “Almanack” for 1762, a spelling book, broadsides, and several reprints of earlier books. As time went on, he was involved in printing government orders including a set of the Delaware Laws.

Isaac stayed with Adams until 1766 when, due to a downturn in business, he was sent to another print-shop to finish his last year of apprenticeship. He wound up working for William Rind in Williamsburg, Virginia. Rind was a Whig, and was publishing a newspaper, the Virginia Gazette.

The Stamp Act of 1765 impacted many facets of commerce, including the printing business: the paper was taxed, it also charged two shillings per advertisement, it had taxes on pamphlets, almanacs, legal and business forms, and a special toll on apprenticeship indentures. Williamsburg was still abuzz about the act when Isaac arrived.

Being a Whig, Rinds printing shop was the only printer in town that wasn’t controlled by the loyalists. As such, Rind was chosen by Thomas Jefferson to print a “Free Paper”(meaning a paper free from gov’t interference in publishing). The Virginia Gazette’s motto: “Open to ALL PARTIES, but influenced by NONE.” – A distinct impression made on the Isaac that he would repeat much the same words later in life. With Rind, Isaac Collins printed not only the newspaper, but an almanac and several works of governmental laws.

On his 21st birthday, Isaac Collins finished his apprenticeship and sought out his own way in the world. He went to Philadelphia, PA to work as a journeyman printer with William Goddard.

Goddard had already made a name for himself, and had been printing the Gazette in Philadelphia, as well as having a contract to print government papers. Collins worked with Goddard for about 4 years.

In 1770, during a religious meeting, Collins met Joseph Crukshank, who had just set up his own printing office the year prior. They hit it off and began a partnership, and started working together. They did not work together long, however, and later that year, Isaac Collins set up shop in Burlington, New Jersey, which had at that time no print shop there, and was the added benefit of being a large Quaker colony.

While setting up his business in Burlington, Collins met John Smith, a Quaker and a member of the Governor’s Council, and NJ Legislator. The Smith family controlled most of the religious and political activities in town. John Smith was an influential character who helped Collins set up his printing business.

The history of printing in NJ was at that time very short, but included a few items of interest. In 1723 William Bradford issued a set of New Jersey laws for the Assembly, and in in 1728 Samuel Keimer set up a shop in Burlington. In this Burlington shop, he employed a young Benjamin Franklin, who was involved in printing, among other items, paper currency. Around the month of August in 1770 Collins set up his shop in Burlington, New Jersey at 206 High Street, the very same printing shop that Ben Franklin had once used. He began working on the “Burlington Almanack” soon after he opened his shop, and the first issue went on sale by September 24, 1770.

Collins was also keen to succeed the recently passed James Parker, who was the official Public Printer, which was also the official governmental printer for the area, but having his print shop in Perth Amboy, N. J. Parker died on July 02, 1770, and Collins just happened to be in the right place at the right time to apply for the position. Also wanting the position was Samuel Parker, the late Mr. Parker’s son. In Collins’ favor though, was the fact that the position would be granted to the person who had the better political connections, such as he had recently obtained through the influential Smith family, and others of the Quaker faith in the area.

On October 02, 1770, Collins had been awarded the lucrative position of Public Printer, which would ensure that he would have a sizeable amount of work to get him well on his way in his new business. A typical governmental contract for this position guaranteed about 250 pounds sterling a year.

He was officially, and verbosely, proclaimed public printer, and thus printer to the king: “assigned, constituted and appointed … Printer for our province … Together with all Salaries, Fees, Perquisites, Profits, Privileges and Advantages to the said Office belonging in any way appertaining, for and during our will and pleasure.”

In addition to his governmental work and his almanac, Collins had a busy first year, printing other items, including reprints of books such as “History of Belisarius, the Heroik and Humane Roman General”, “Adventures of Telemachus”, “Compendium of Surveying”, the popular “Oeconomy of Human Life”, etc.

Amazingly, he also had time to continue courting, fall in love and, on May 08, 1771, got married to Rachel Budd, and moved into a house on the corner of High Street and Union Street.

Collins was an early abolitionist, and he was known to print pamphlets and broadsides on the subject. He reprinted a work by Anothony Benezet titled “Brief Considerations on Slavery, and the Expediency of Its Abolition” and Observations on Slave keeping, as well as Granville Sharp’s piece titled “An Essay on Slavery, Proving from Scripture Its Inconsistency with Humanity and Religion”.

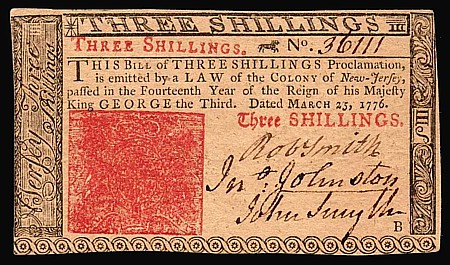

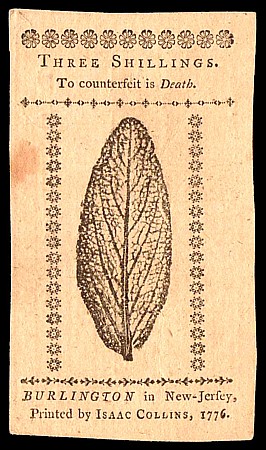

One of his official duties as a Public Printer included the printing of “bills” or paper money. In 1775 Collins started printing banknotes based on the Provincial Assembly’s authorizations to print 50,000 pounds worth, with the king’s approval, of course.

Collins was experienced in this method of printing already, and was able to do so quite readily. But in addition to his duties to the king, printing his banknotes and laws, etc., he was also charged with being a servant of the colony, which was having him print works for the provincial government, which was morphing into the continental government. These other works included ordinances and a state constitution. By 1776 he had even been printing broadsides for enlistment into the militia.

Collins was able to keep his feelings separate from his business, but he was known to be in favor of the “New State” of government, which was in opposition to the official Quaker stance, which was more or less neutral. Collins even submitted a recommendation for a friend and fellow printer, Shepard Kollock, to receive a commission in the Continental Army. Collins did, however, give in to his political feelings in June 1776, when he refused a printing job for the Colonial Governor, William Franklin, who had been arrested for violating the provincial laws of forbidding any government to exist that was subjected to the British Crown. Franklin (who was actually the estranged son of Benjamin Franklin) wanted to address the public and the assembly by publishing his testimony, but Collins steadfastly refused, believing that it would serve no good purpose to the revolutionary cause.

There had been talk within the fledgling government that a local Whig/Patriot newspaper was needed to could disseminate information and be used to refute the misinformation that the loyalist Tories would publish in newspapers under their control in nearby New York. So, on November 06, 1777, Collins received authorization from a special council of the Assembly to start printing the New Jersey Gazette. To ensure that the newspaper would be able to survive the first few months of publications, the committee also authorized a subsidy of subscriptions for a minimum period of six months. There was one other problem to be hurdled, too: The militia requirements would leave Collins’ print shop without enough employees for months at a time. He simply would not be able to produce a paper without his skilled employees. Under the circumstances, the committee further granted an exemption from military service for Collins and his employees, as well as Collins’ paper supplier, William Shaffer and his two employees.

In order to maintain a reliable distribution of the newspaper to the furthest distribution points, a ‘cross post’ system was created, in which the post office would deliver the newspaper as well as the regular mail items.

In his first issue, Collins published his paper’s plan of what he would be delivering to the public through his paper. He promised to print once a week, print faithful accounts of occurrences of foreign and domestic news, governmental and judicial news, essays, “schemes” for increasing economy, Hemp and Flax agricultural news, to support religion and liberty, and “Will spare neither cost nor pain to make his paper as useful and entertaining as possible.”

In 1778, after only 13 issues were printed, Collins moved his home and business from Burlington to Trenton, New Jersey in order to take advantage of the geographic and industrial advantages that Trenton had. His move was successful. So much so that he had to announce a suspension in new subscriptions because he could not keep up with the demand.

Still, there were problems for Collins. Wartime inflation, monetary deflation, paper shortages, and then the following year, in February 1779, Shepard Kollock the gentleman he had recommended for a commission in the militia, now released from his military duties, opened his own printing shop and started to publish his own newspaper in Chatham, the New Jersey Journal, in the Northern half of New Jersey. If that wasn’t enough, the Quakers decided to “disown” Collins due to his support of the revolution, its government and military actions (his exemption of military service to provide newspaper service to the new government was seen as being akin to military service by the Quakers.) This must have hurt Collins deeply, but his faith in the new government outweighed his faith in the tenets of his church, at least for the time being. Fortunately his ‘disownment’ applied only to him and not to his family, who were allowed to join the church in Trenton. Collins remained separated from the church for almost ten years.

If his relationship with the church was strained, his position with the paper was not. He continued to inform the public of necessary things through his paper. In January 1778, he reported the presence of counterfeit $30.00 bills in the area of Burlington, N. J.: “They are dated May 10, 1775, done on copper-plate, and easily discovered. The figure of the lower ship in the true bill, especially at its bottom, is much blacker and less discernible than in the counterfeit; and the paper in the latter is much thinner and smoother. And in that of the counterfeit in the upper ship a ray of light appears between it and the representation of the sea, which is not so in the genuine bill.” He also informed than that the work Philadelphia was misspelled as “Philadelpkia”.

In 1779 he had more troubles. He had printed an article by a person called “Cincinnatus” which remarked badly against the then Governor Livingston, and the College of New Jersey. The Assembly took the view that “the freedom of the press ought to be tolerates as far as it is consistent with the good of the people. And the security of the government established under their authority.” The assembly thus required Collins to produce the real name of “Cincinnatus”. Collins, of course, refused. He held fast to the notion that the opinions of the writers are not necessarily the opinions of the editor. He wrote in a letter to Governor Livingston, “My ear is open to every man’s instruction, but to no man’s influences.”

Collins was not compelled to release the name. He went on publishing his paper right through the end of the war, when he printed Governor Livingston’s announcement that the war had ended. Collins had won a great deal of reputation as a printer. He had printed all manner of products, from paper money to books, newspapers to magazines. In 1789 he decided to print what he and others would consider his most important item yet. Collins was to print an English language bible, only the second printing in the Americas. His experience and adherence to quality ensured him the backing he needed to undertake this task. What was to be known as the Collin’s Bible was a King James Version, was released as early as January 11, 1792 and was renowned for its accuracy, having far less mistakes than other bibles were known to have.

Collins continued on with his printing business, opening several print shops and had become a leading publisher of scientific books in the young nation. Isaac Collins died on March 21, 1817 of a stroke. His children continued to operate his business for over 30 years more.