NORTH CAROLINA COLONY

John Ashe

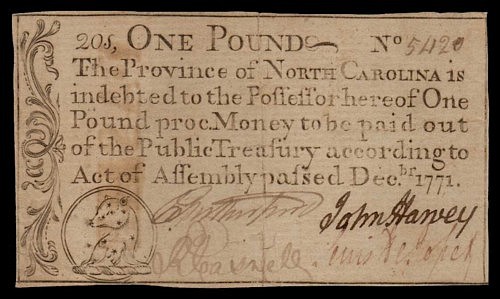

Authorized by an act in December 1771, this note was one of 10,000 1 Pound notes to be issued in the Colony of north Carolina. Along with other denominations being issued the combined total was 60,000 Pounds for this issue. The signatories were Richard Caswell, Lewis De Rosset, John Harvey and John Rutherford. The notes issued in this series each have a small vignette in the lower left corner. Each vignette corresponded to one of the ten different denominations that were issued by this act. This One Pound note features a bear in pose with the constellation Ursa Minor, which is also known as the Little Dipper. The last star of the bear’s tail, or the dipper’s handle, is of course the North Star.

Richard Caswell, born in the Colony of Maryland in 1729, but moved to North Carolina in 1746. He had a long and distinguished career in service to the United States and to North Carolina. He started as the Colony’s Deputy Surveyor, obtained his legal degree, and practiced law in Hillsboro. He fought in several battles throughout the Revolutionary War, and was eventually promoted to Brigadier General. He was one of the first members of the Continental Congress, and was also elected as North Carolina’s first governor, and then again as its fifth governor. He was still serving North Carolina, as the Speaker to the State House of Commons, when he died in November 10, 1789.

Lewis De Rosset was a Loyalist, not a Revolutionary. He was a member of the Lower House of General Assembly, Chairman of Public Accounts and also served as Justice of the Peace. De Rosset served as Lieutenant General under William Tryon, the Colonial Administrator (British Appointed Governor) in 1768, and as Adjutant General under General Waddell of the Militia as late as 1771.

John Rutherfurd emigrated from Scotland and was in the Colony of North Carolina by 1732. He had a mercantile and a lumber business and married a well-to-do widow, Frances Johnston, in 1751. He had served as the Wilmington Town Commissioner twice, in 1749 and again in 1751. He was also appointed as the Receiver General of the Kings Quit Rents (a type of land tax for lands owned by the King), serving until the demise of the British Government in North Carolina. He too was a Loyalist, and served as a Lieutenant General under William Tryon, establishing the Cherokee Boundary line and the Boundary between North and South Carolina. He stayed in North Carolina until Yorktown fell, and then sailed to England, dying in route in 1782.

John Harvey was a Revolutionary who had served as Speaker to the State house of Commons, and represented Perquimans County at the Colonial Assembly in 1755. In 1766 he served as Speaker of the Colonial Assembly under Colonial Governor William Tryon. in August 1774 he moderated the First Provincial Congress, in direct violation of the orders of the British Administration. He convened a second Congress in April 1775. Shortly afterwards, he fell from his horse and became seriously ill from the injuries. John Harvey died in May 1775 as a result.

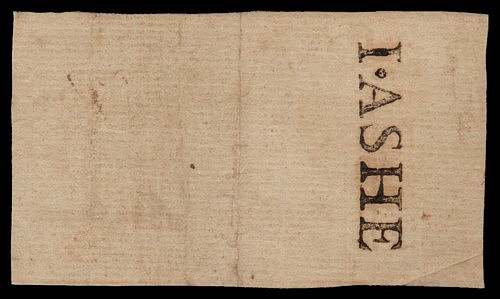

But the real star of this banknote is actually on the reverse. The back of this note has a stamped name of I.ASHE (the capital letter I at the time actually standing in for the letter J). This stamp is for Mr. for John Ashe, who was the Treasurer of the Southern district of Colony of North Carolina.

Born in 1720, John Ashe, the son of Colonel John Baptista Ashe, was orphaned at 14 years of age with three siblings to look after. His Uncle Sam Swan was able to look after him however, and saw to it that the young John was able to be properly educated. He attended school in England but returned to North Carolina to make his living. He was fond of reading, and had such a valuable library that, during the revolution, he hid it in the hollow of a vast cypress tree in the Burgaw swamp.

By the age of 31 he was the Justice of the Peace for New Hanover County, and at 32, he was elected to the Assembly where he served along with his Uncle Sam Swan. Ashe continued to serve in the Assembly for many years, and he saw that there were injustices in authorized payments, such as money earmarked for schools, being sent back to England or used for other projects in North Carolina. By December 1758 He had seen too much of it to suit his tastes and, when the Assembly met, John Ashe took advantage of an opportunity to send correspondence to King George III. In it, he remarked that over the years, North Carolina has had to divert money for schools to be used for the defense of the colony against the Indians. He asked the king to reimburse North Carolina for these monetary burdens and to have that money used to build a free school in each of North Carolina’s counties. Amazingly, funds were granted by the King, but North Carolina’s Governor Dobbs saw to it that the money was spent on his own needs instead. John Ashe served in the militia as an officer and in 1754 when the French and Indian War broke out, had been promoted to Major in Colonel Innes’ Regiment.

In 1762, Sam Swan stepped down as speaker of the Assembly, and John Ashe was selected to serve in his stead. In 1764, the colonies were informed of the Stamp Act, in which they would be taxed in order to help support the British Empire. This was an exceedingly unpopular act both in the colonies as well as among the English Merchant Class who were afraid of losing business with the Americas. As Speaker of the Assembly, Ashe was in favor of opposing the act in any way possible. The fervor of the colonist over the taxation was increasing, and as a result, many persons in North Carolina set up looms in order to weave their own clothes instead of buying them from England.

In 1765, Colonel Tryon succeeded Dobbs as Governor and changed the Assembly meetings to May 3rd, 1765. This change was an attempt to stall the meetings in order to stall any action by the North Carolina assembly to oppose the act. The Continental Congress was set to meet in New York City on October 07, 1765. Ashe was going to take part in the Congress or at least send a representative, but Governor Tryon again postponed the meeting of the North Carolina Assembly, and continued to do so repeatedly, eventually dissolving it. As a result, no North Carolina delegate was sent.

The Stamp Act was passed in March, and Mr. William Houston was appointed the Stamp Master in North Carolina. Even though the stamps were still in route from England, North Carolinians were taking matters into their own hands. On November 16th, 1765, William Houston was seized by a force led by Moses John de Rosset (father of Lewis John de Rosset) and ordered to resign his position as Stamp Master. Two days afterward, John Ashe, together with 50 others gentlemen, informed Governor Tryon that they would not allow the Stamp Act to be enforced, and that they would resist it “to blood and death”.

In the meantime, the stamps arrived, but with no one to turn them over to, they remained on board the ship. This caused a sudden stop in commerce, as ships that were coming and going were stopped and seized by the British for not having the proper stamps. The Mayor of Wilmington resigned and was replaced by Moses John de Rosset. General Hugh Waddell was placed in command of the 1,000 strong militia force, which was in turn under the command of the Speaker of the Assembly, John Ashe. This militia was on the move. Making their way to Brunswick they took control of Fort Johnston and detained the officers and officials until the release of all merchant vessels was secured. In part due to this action, the Stamp Act was repealed in March of 1766.

At the next meeting of the Assembly, John Ashe was absent for the first few days. As a result, John Harvey was elected as the Speaker, while John Ashe was elected as the Treasurer.

By 1768 John Ashe was appointed a Major General in the Militia, and he was called upon to end a riot in Hillsboro. This happened again in 1771, but there were no official funds to be had to pay the expenses. Ashe was compelled to pay the funds from his southern district and issued his own banknotes to pay for the military action, and the rioters were thus routed in large part to John Ashe using his position to fund the excursion.

However successful he was in this matter, in following the dictates of the assembly to not collect a particular one shilling tax, the governor disbanded the Assembly in 1772 and ordered a new elections. John Harvey was elected as Speaker, and Richard Caswell was elected as Treasurer. This move assuredly helped propel Ashe into his next career.

Ashe had been a Colonel of the New Hanover Regiment, but he resigned and further declined a reappointment to this position. Ashe had by this time started to form a separate militia group, and had in fact been the very first North Carolinian to accept a commission “at the hands of the people.” Ashe had in fact been instrumental in getting persons to enlist in the new militia and had even threatened bringing legal action to those who would refuse service to the militia.

On April 19, 1775 the Battle of Lexington commenced which effectively started the Revolutionary War. When news of the success of the Colonists reached the governor, he fled his estate and took refuge in Fort Johnston, fortifying it against attack. Ashe had taken it upon himself to route the governor from North Carolina, and reportedly Ashe himself set fire to the fort, causing the governor to flee to ships in the harbor; North Carolina was no longer under Royal Administration.

In February 1778, Ashe was appointed Brigadier General of the Wilmington District of militia, a force of some 9,000 men. He successfully defended against the British invading Cape Fear in April and by the end of May had sent the Redcoats back to their ships.

Ashe continued to serve civilly as well as militarily, and in December 1776, was again appointed as treasurer of the Assembly, while Richard Caswell was elected as Governor of the Assembly. In 1868 he was commissioned Major-General and sent south to Elizabethtown to command a gathering militia force there. Governor Caswell offered to take over the duties as Treasurer, but wrote to Ashe on December 29, 1776, that he was concerned that the militia had insufficient numbers of firearms and that many of those which were available were not fit for service. It was reported in January 1777 that of the 5,000 men ordered out, “not more than half had marched, and those badly armed.”

This was a warning that things were not going well. Ashe’s subordinate commanders placed their soldiers in positions that were poorly defensible and when the British came to meet them, many of the militia quickly threw down their firearms and fled. Ashe tried to regroup the forces, but the pandemonium was too far gone. Ashe was held responsible for this defeat and, when his militia was disbanded, he returned home himself never again taking military command.

When British took control of Wilmington, North Carolina in January 1781, John Ashe fled into the Burgaw swamp. He was pursued by the British and shot in the leg, but survived and was taken prisoner. While in prison he contracted the dreadful smallpox disease, but survived the infection. He was paroled and he returned home, but he did not wish to stay in occupied Wilmington, and he took his family to the country. Along their journey, he stopped at the home of Colonel John Sampson, where he was taken ill and died that night.

John Ashe was an instrumental figure in the North Carolinian fight for freedom, fighting against the injustices that he saw in the political and economic spheres in which he travelled. His troubled beginnings were set into this course of action by his Uncle Sam Swann, but his conviction to duty was absolutely his own. He was a gentleman, whose generosity and valor, together with his ability to fight when needed were indeed his strengths. He was not mislabeled when he was remembered by the historian Thomas Jones as perhaps the most chivalric hero of the Revolution.