Rhodesia

The Great Zimbabwe

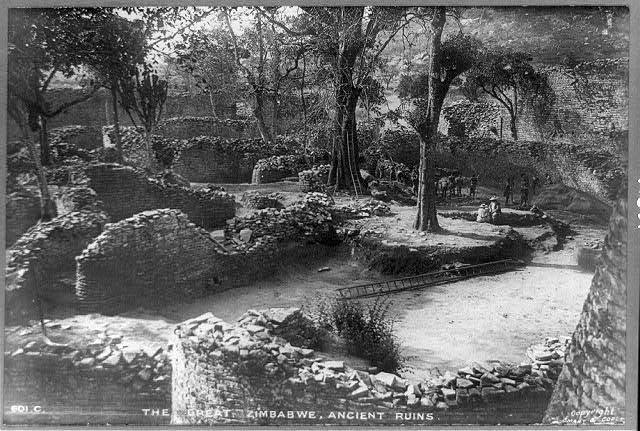

Located about 30 kilometers southwest of Masvingo in Zimbabwe there is a unique massive stone complex called The Great Zimbabwe. It is the largest to be found in Africa south of the Pyramids of Meroe located in Sudan. The Great Zimbabwe complex was named a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1986.

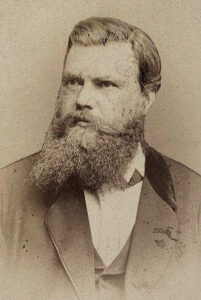

In 1871 a German explorer named Karl Mauch made an expedition through a section of Africa then known as Mthwakazi, later called Rhodesia and what is now known as Zimbabwe. Mauch was a driven man who was obsessed with travel to Africa from the time he received an atlas as a child. He studied hard and worked hard, and though unable to attend university, he did attend a Teacher’s Training College and was for a time an assistant teacher. He taught himself further in the fields of math, geology, medicine, botany and learned English, French and Arabic.

Mauch was the kind of person who threw his whole self into his work. Evidence of his determination is illustrated in his preparation for travel in Africa, when he evidently even took to sleeping in bed with snakes in order to prepare for that eventuality in his explorations in the wild. When Mauch reached southern Africa he worked as a laborer until he was able to get hired on doing exploration work. He honed his skills at mapping, taking detailed notes, surveying and exploring in general. After a few years working in south-east Africa, Mauch heard a rumor from German Missionaries about some large ruins that they had tried to reach earlier, but had to turn back due to sickness among some of their guides.

Emboldened by these reports, Mauch soon embarked on an expedition looking for the lost city, meeting with several misadventures along the way. He rescued 5 kidnapped children and reunited them with their parents, was himself captured and suffered attempts at poisoning him. He also needed to be rescued from captivity among the Shumba tribe, was robbed by raiders from other tribes and even his own porters, had an attempt to sequester him on a hilltop by another tribe to be their “White Man”, from which he was rescued again by another explorer Adam Renders. Finally, on September 05, 1871, after goading his guides to accompany him on the climb up a mountain that they thought was haunted (Mauch called it Spook Mountain!), he reached the hilltop where they caught a glimpse of the Great Zimbabwe complex 5 miles distant. Given the hostility among the tribes in the area, Mauch wasn’t able to fully visit the site until six days later, when Mauch, Renders and a game hunter named George Phillips all entered The Great Zimbabwe ruins.

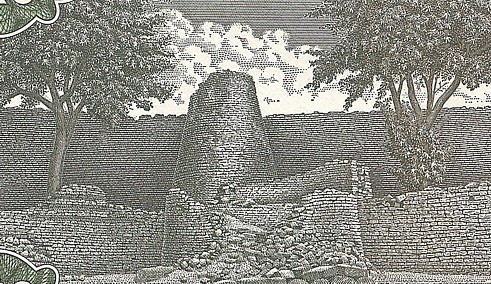

The Great Zimbabwe complex covers about 60 acres in area (the size of 180 Boeing 737’s), and has three distinct sections. It was made of granite slabs sourced in the local area outcroppings. One most intriguing aspects of the site is that the stones use no mortar. There was found to be a mix of clay and gravel that formed a rounded cap on the walls, but between the rocks and bricks, no mortar was used. Each layer is set in ever so slightly to provide stabilization.

The first section of the complex is a fortress like area full of walls set into a labyrinth of passages is called the Hill Complex (it was previously called the Acropolis) with walls skillfully melding into the natural curvature of the rocks on the hill. This is now thought to have served as a religious center for the area, as well as the residence of the king.

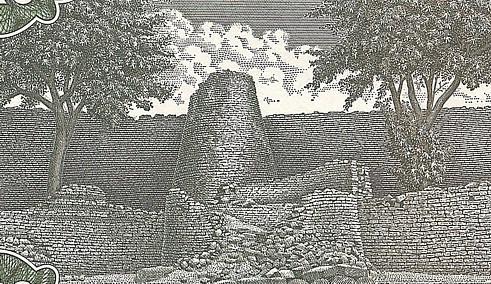

Another section is an immense elliptical enclosure in excess of 100 yards and 70 yards wide, or 820 feet (250 meters) circumference. Within this enclosure is a tower with walls more than 30 feet (9 meters) high and 20 feet (6 meters) thick. This is where modern researchers think the lesser royal family and other elite members lived. Between the enclosure and the fortress is the third section called the Valley Complex, a large area made of smaller individual buildings where many shops and houses were.

Mauch was unable to conduct a proper survey as his instruments and much of his luggage was lost by porters earlier in his expedition. Political strife between his hosts, the Amangwa, and the Karanga peoples limited his ability to come and go as he wished. Both tribes were claiming ownership of the ruins and the land around it, and were prone to hostility towards each other. All Mauch was able to do at the time was to make some sketches and a report of his findings. This is where Mauch was able to shine despite his loss of equipment, lack of supplies, hostile environment, and harsh treatment from several of the locals. His experience in making maps and drawing during his previous expeditions enabled him to make very detailed drawings and maps of The Great Zimbabwe complex.

Mauch was undoubtedly amazed at the site, but he also misinterpreted much of it. Given that the population of the day were living in primitive mud huts, it was inconceivable to Mauch and many early explorers and researchers that this could have been built by ancient African peoples. Later researchers have maligned Mauch and his contemporaries for his assertions that the structures were built by non-Africans, but given the education that he had received, the state of local societies in the area at the time and the legends that circulated concerning lost cities, it can be understood why he had thought so, viewing things through a European prism, even if the evidence for his assumptions was not there.

Some of the legends of lost cities included stories of Queen of Sheba’s capital and King Solomon’s lost mine, which would have accounted for the king’s massive wealth. There was also the city of Ophir, a type of “El Dorado” in Africa, which was referenced to several times in the Bible, making references to large amounts of gold that was obtained there. Then there was the story of Prester John, a legendary king who ruled a Christian kingdom in lands unknown, but thought to be somewhere in the Orient, possibly in Africa. As silly as these seem to us today, they were not as silly in years past, when large areas of the continent were still unexplored.

Unfortunately, then, as now, a man without formal training and no university degree is often disregarded by those who do have them, and despite his discovery and reports, he was not allowed to obtain any post in a museum or university to more fully elaborate his findings properly. So after his return to Germany, Karl Mauch eventually settled for a job as a manager at a cement factory in Wuerttemberg, Germany. He suffered from ill health due to fevers he contracted while in Africa, and he was plagued with insomnia. Mauch would die April 4th, 1875 after a fall from his hotel window in Stuttgart, Germany. It is not known if he died from an accidental fall or if it was suicide.

Ironically, the next year saw the publication of Mauch’s reports, generating a lot of interest as reports of finding lost cities do even today. More expeditions found their way to The Great Zimbabwe in the years following Mauch’s death. Unfortunately the lack of written history in the area, combined with acidic soils that decomposed physical traces of human activity and the assumption that if modern Africans did not make even better structures now, then their ancestors could not have built it, were all party to the delay of realizing that the structure was indeed made by Africans.

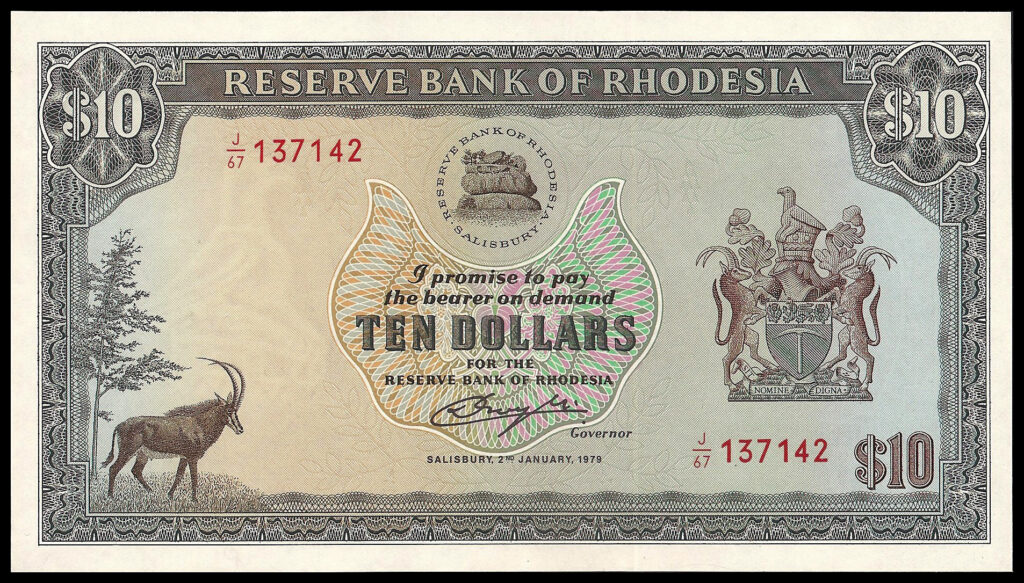

Excavations that followed were conducted with the precision of the day, which is to say that there was little to no record of actions taken by the archaeological teams. Items that were dug up were catalogued but had no records of the exact locations, no remarks on depth in the soil they were found in, and though many items were identified as being made in the local area, they were considered to be unrelated to the complex. Some of the items found included iron spear and arrow heads, pottery fragments and eight soapstone carvings of birds. It is a soapstone bird carving that is used as a symbol of modern Zimbabwe, is found on the Zimbabwe flag and is used as a decorative image and watermark on banknotes.

Eventually an archaeologist named David Randall-MacIver made a professional assessment of the area, coming to the conclusion that the site bore no resemblance to European, Arab or Oriental design and was undoubtedly constructed by Africans during the 14th century. He had his detractors though; mainly people who held the local population in low regard and assumed that their ancestors could not have had the intelligence or skills to build such a structure. Then in 1929 archaeologist Gertrude Caton-Thompson’s findings supported MacIver’s and she found evidence of beads in the surrounding soil suggesting that the foundation was built in the 9th century AD, and that the main structure was likely built in the 13th century. She found that the entirety of the structure was undoubtedly built by African hands and has no resemblance to any outside culture’s influence in design or form.

More recent studies have yielded some additional clues. It is thought that there were about 300 elite members who would have lived within the main structures, while most of the others lived in the valley area or in nearby areas. The total population is estimated to have possibly been about 18,000 at one time.

Researchers also discovered that it was a hub for trade with coastal cities and Arab and Indian traders. It is thought that The Great Zimbabwe was able to conduct trade with items of ivory, copper and gold, found in surface deposits and panned from the nearby rivers, which were highly desired trade goods. Evidence recently discovered included Chinese stone vessels and celadon glassware as well as Ming Dynasty pottery, coins from Kilwa Island off the coast of Tanzania and Persian glazed ceramics.

The demise of the complex, while unknown, can be speculated on. It is probable that the end of the Great Zimbabwe was a series of issues that compounded to a slow decline. With such a large population, it is possible that the farming practices were not developed enough to sustain the population, or that the ivory and precious metal sources ran too low to keep the area on traders’ routes.

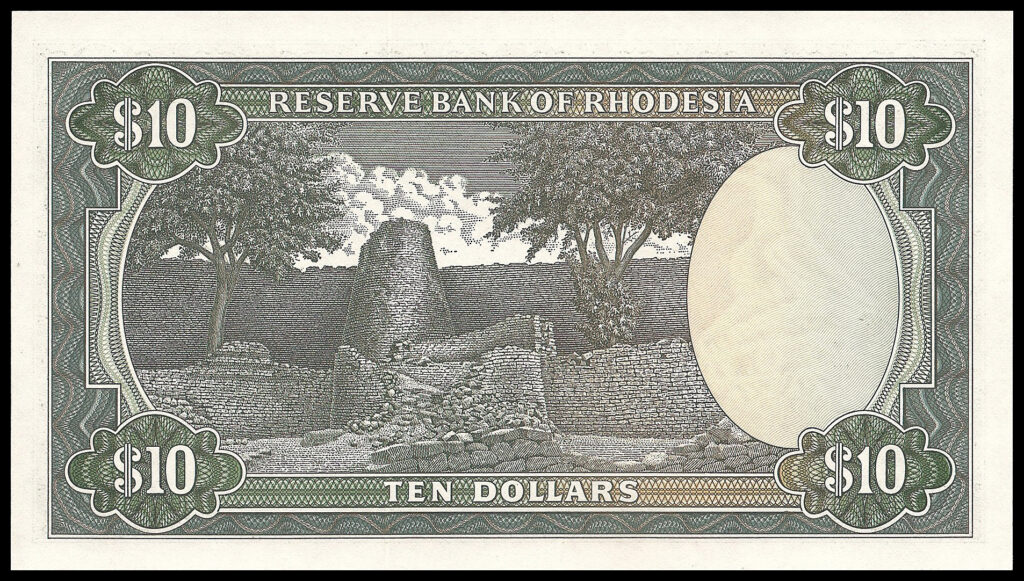

Though many of the details of The Great Zimbabwe have been lost, it is still a magnificent testament to the abilities of the people in the past and serves us a healthy dose of humility when we assume that our ancestors could not possibly have created something magnificent in their day that we would have a difficult time creating today, and serves as a fitting tribute on the back of this Rhodesian $10 banknote issued in 1979, the year the country became and independent nation, soon to be known itself as Zimbabwe.

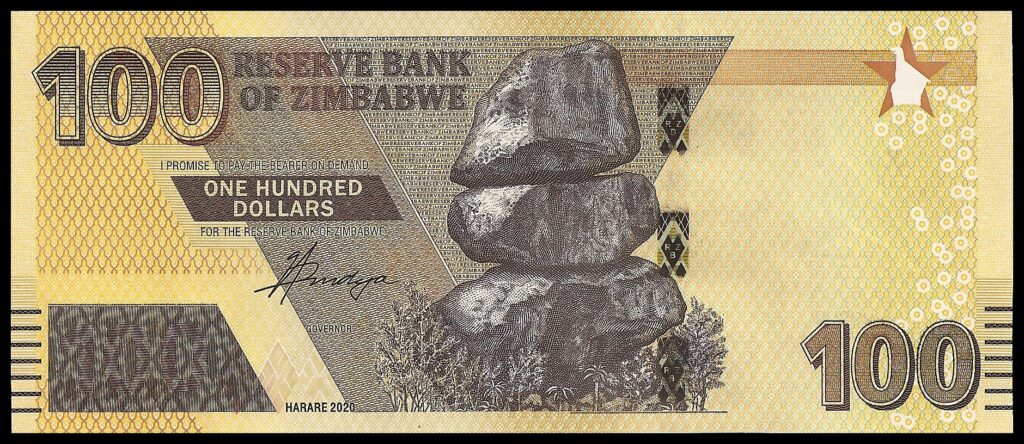

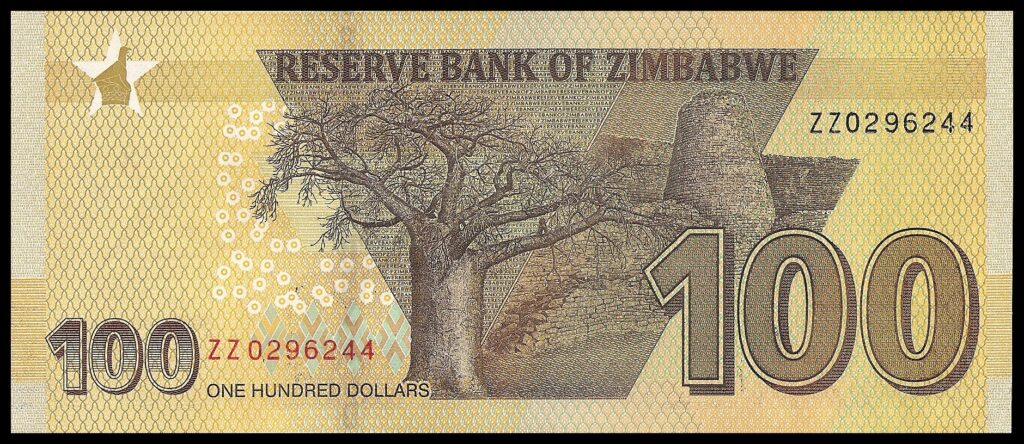

After Rhodesia was split up, the lions portion became Zimbabwe, which also included the Great Zimbabwe. On the 100 Dollar banknote issued in 2020 there are large rocks on the front which are the balancing rocks at Chiremba. The reverse shows a tree prominently in the center of the note, and The Great Zimbabwe in the background, outlasting nations, yet bringing the people together with their past.