RWANDA

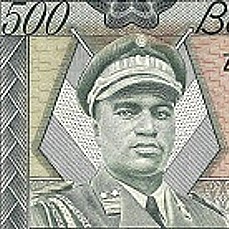

Juvenal Habyarimana

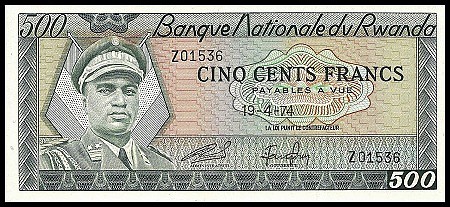

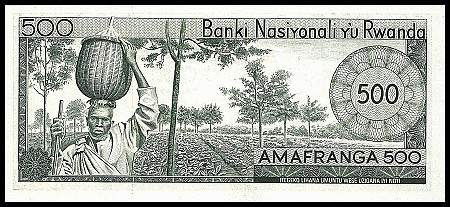

Juvenal Habyarimana’s portrait is on the 1974 issue of the 500 Franc banknote one the year after a bloodless coup made him president. He is the only dignitary whose portrait has ever been on a Rwandan banknote. Though there have been people on their banknotes, these have been either modeled after everyday people or allegorical representations. This banknote is a special issue of the 500 franc note issued from 1964 through 1976, which has the country’s arms where Juvenal Habyarimana’s portrait is on this note. Its printing was within the regular run of banknote issues, lasted only 6 months and with a five-figure serial number, was limited to less than 100,000 issued notes. He was, to some, a hero and a liberator, but to others he was a symbol of their oppression, which led to a horrible time for Rwanda and several other countries. His rise to power was in part due to an racist attitude of a colonial era that still pervades the region today.

During World War I the Belgians began their occupation of the Rwandan territory, which was to become known as Ruanda-Urundi by 1923. Belgium was given the right to occupy and govern the territory as a result of post World War I settlements laid out through the League of Nations. In 1925 Belgium was also governing the Belgian Congo (later Zaire and now the Democratic Republic of the Congo) which was administered from Brussels, Belgium while the Ruanda-Urundi territory was administered chiefly by the a group of natives known as Tutsi. The Tutsi, along with another native group known as Hutu, made up the vast majority of the native people in Ruanda-Urundi as they do now in modern Rwanda, with only one percent of the native people being Twa, a pygmy race who are the oldest recorded inhabitants of the area. The problem with the government of Ruanda-Urundi being administered by the Tutsis is a long held rivalry between the two peoples.

The Tutsis originally came from Ethiopia and were cattle ranchers while the Hutus came from Chad and were more agrarian in their nature, and the Tutsis saw themselves as being slightly higher class people over the farming Hutus. Essentially, the original strife between the two peoples boiled down to class warfare, yet the Tutsis and the Hutus pretty much got along. In fact, any differences between the two people are very slight, though the Tutsis are thought to be somewhat taller. They lived peacefully among each other for centuries. The Belgians saw the Tutsis as having a degree of superiority over the Hutus based on their facial characteristics, which were closer to the European than the Hutus were. This fact helped the Tutsis to be placed in to an elite status as a ruling class. When Belgian authorities placed the Tutsis in power, they segregated the two peoples, and trouble began to brew. Soon after, the Belgians issued Identity cards based on the person’s race as either Tutsi or Hutu, or Twa, and people could then be classified and segregated into their respective classes. Into this situation, Juvenal Habyarimana, a Hutu and future president of Rwanda, was born on August 3, 1937, the son of a wealthy landowner.

Through the years of his youth, Juvenal Habyarimana saw some changes in the role of power. He saw the Belgians change to secret ballots, which allowed the Hutus to make larger political gains. He saw the Tutsi king, in an effort to create a more equitable nation, make changes in land and cattle ownership rules, which emboldened Hutu separation from the Tutsi who were seen as losing control of the cattle, a long held class distinction. Yet, Hutus did not have the same opportunities as the Tutsi in regards to education or employment. As time went on, resentment of the Tutsis grew, and by 1959 a riot broke out, which has come to be known as the Wind of Destruction, which led to the overthrow of the Tutsi King Kigeli V and the slaughter of up to 100,000 Tutsis. Many Tutsis fled from Ruanda to the safer Urundi territory. A new Hutu leader, Gregoire Kayabanda, led a provisional government in his until independence came from the Belgian Government in 1962. Independence came in two sections: Rwanda ruled by the Hutus and Burundi ruled by the Tutsis.

In 1962 Juvenal Habyarimana was in the Rwandan National Guard serving as a platoon leader, and by 1965, at only 25 years of age, he was appointed the minister of the armed forces by President Kayabanda. Juvenal was in a position of great power and he had a vision of a peaceful government. Yet, though Rwanda was now ruled by the Hutus, there was still a large amount of reprisal attacks from Tutsis in the following years. So in 1973, frustrated with Kayabandas inability to put an end to the violence, Juvenal Habyrimana led a peaceful coup and removed Kayabunda from power and took the seat as president promoting nationalism and an end to ethnic violence. With such peaceful aspirations, Juvenal received support from governments throughout the world. In 1975 he created a one party system, and by 1978 installed a new constitution, allowing for elections. Even so, he was the only candidate on successive re-election ballots.

To aggravate his efforts, domestic issues arose including plummeting coffee prices and refugees flooding into Rwanda’s borders. And through his efforts, Tutsi reprisal attacks ensued. Juvenal instituted democratic changes including a multi party system, but the resident Tutsis, now a minority, could not obtain political power even with a two party system.

Civil war came to Rwanda in 1990 when Rwanda was invaded by the Tutsi soldiers called the Rwanda Patriotic Front. This ethnic based civil war lasted three years, ravaging the economy as Hutus and Tutsis killed each other. The United Nations brokered a peace deal with Juvenal Habyarimana and the Rwanda Patriotic Front, allowing the Tutsis equitable representation in the armed forces as well as in political positions. Yet there arose tensions with the actual political positions that the UN Deal never settled. Amid the bickering political mess, armed Hutu militias formed in hopes to drive out the Tutsis, and the new government never took control.

On April 6th, 1994, while returning from a meeting on ethnic violence, Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane crashed and he was killed. Also killed was Cyprien Ntaryamira, the president of Burundi. There were reports that the plane was shot down, leading Hutus to blame the Tutsis for his death, but this was not verified. Others believe that Juvenal was killed by his own Hutu government for his agreeing to the UN Peace deal, allowing Tutsis to have equal power in Rwanda. The truth didn’t matter. As each side blamed the other, it was reason enough to start another full on ethnic war. No one was safe. Hutus and Tutsis were murdered openly. Red Cross volunteers and even UN troops were killed if they were in the wrong place at the wrong time. With the President gone, and a nonfunctioning government, anarchy laid waste to the land and people. Genocide ensued in a most gruesome manner. People were shot, hacked with machetes and run over. Militias forced civilians to kill their neighbors who were not of the same race. Inborn children ripped from the womb. In an effort to bolster the genocide, people were promised the lands of those they killed. In the course of three months, over 800,000 people were murdered and over two-million people sought refuge in neighboring countries. In July, the Rwanda Patriotic Front captured the capital, Kigali and called a cease fire. Rwanda was now under Tutsi control again, and many Hutus fled the country in fear of reprisals from the Tutsi government. Rwanda celebrates April 7th as Genocide Memorial Day.