SÃO TOMÉ E PRINCIPE - Saint Thomas & Prince

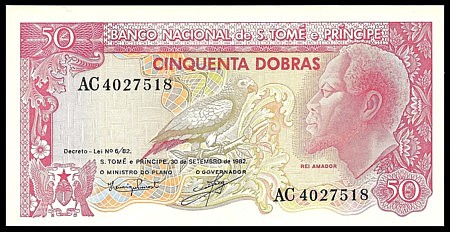

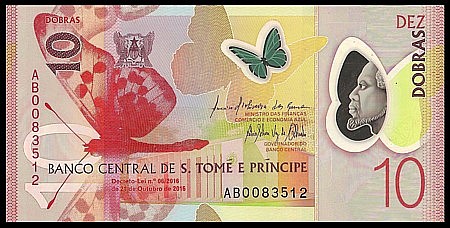

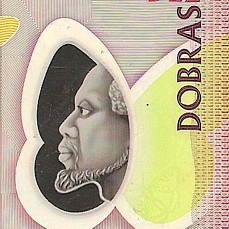

Amador Vieira

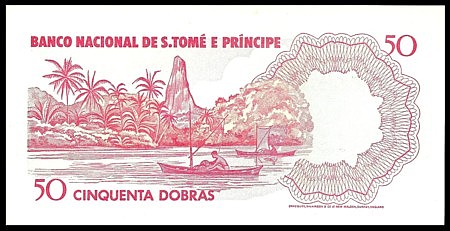

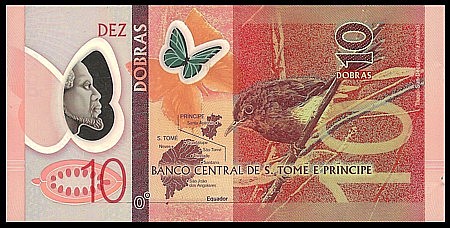

São Tomé and Principe is a set of islands off the west coast of Africa, with São Tomé directly west of Gabon and Principe west of Equatorial Guinea. São Tomé is only 25 miles north of the equator, and as such its climate is temperate with most days being in the 70’s Fahrenheit degrees range.

The Portuguese explorers were the first Europeans to discover the islands and found them uninhabited in 1470. The Portuguese named the main island São Tomé after Saint Thomas the Apostle because it was discovered on the 21st of December, which is the saint’s feast day. Principe is so named for the tributes from the sugarcane crops that were paid to the Prince of Portugal.

Just 23 years later, the Portuguese King John II granted Álvaro Caminha as the Governor of São Tomé with the intent of creating a colonial spot for the cultivation of sugarcane. Its tropical climate and ample rainfall made it a perfect location for Portuguese speculators to start a sugarcane plantation on the then uninhabited islands. A plantation isn’t very feasible without a workforce and so, as was common in those days, they decided to use slaves. The Portuguese procured them from the African mainland only 140 miles away. In addition, the Portuguese King John II granted them a workforce of about 2,000 Jewish children from Grenada, all under 9 years of age, whose parents were of mixed race and unable to pay taxes. A very similar agreement developed for Principe as it was developed in 1500. At this time it was in effect a prison colony, and the slave labor ensured that the islands farmlands were prosperous.

Mistreatment of humans often leads to revolt, and on these islands, captive rebellions started in 1530 and by the following year has become such a problem for the plantation owners that they requested assistance from the Portuguese government which resulted in a small ‘bush war’ using armed forces to quell the outbreaks.

The largest slave revolt occurred on the 9th of July, 1595 a slave by the name of Amador Vieira led a revolt that resulted in the slaves capturing the port city of São Tomé. The revolt began as roughly 200 slaves attacked and killed some Portuguese colonists attending mass at a church. Smaller revolts were sparked in other plantations as word of the attack spread throughout the island and over the next few days, and several farms and mills were set ablaze. In a few days the ranks of the rebels had increased to about 2,000 slaves. Though reports of the date varies, it was during the first days of the revolt that Rei Amador is said to have hoisted a flag in front of the Portuguese colonizers and declared that he was the King of São Tomé e Príncipe – an act which garnered him the moniker Rei Amador, with rei in Portuguese translating as king.

Emboldened by their efforts thus far, the rebels again attacked the city of São Tomé on the 14th of July 1595, but suffered heavy losses. This was followed by yet another defeat as the Portuguese cut off the next attack. Not to be outdone by a couple of losses, on the 28th of July, now with as many as 5,000 in their ranks, the rebels again attacked the Port city of São Tomé, vastly outnumbering the defending Portuguese.

Without military training, the massive rebel force was doomed. By this time the Portuguese had been able to procure cannons and entrench their troops and with artillery and hidden infantry, the Portuguese were able to win once again, leaving the rebel forces with the belief that they were simply outmatched by the guns and tactics. Almost immediately many of the rebellious slaves defected back to their captors, and within a few days almost all had capitulated.

Those few who remained with Rei Amador took to hiding the hills, but he was captured and killed the following January. During the short rebellion, more than 60 of the islands 85 mills were burned or destroyed, leaving São Tomé in economic disaster.

Over time there continued to be small rebellions that plagued the islands colonizers, and with the competition of sugarcane plantation in the Americas, it became more difficult to maintain a profitable enterprise, even with slave labor. But slavery was still in São Tomé’s future, and it became a port of commerce for the African Slave Trade across the Atlantic. Slave ships would use São Tomé as a transit stop for their human cargo up until 1876 after the abolition of slavery.

When slavery was no longer a lucrative option and the prices for sugarcane dropping due to the increasing plantations in the Americas, new crops were introduced including coffee, palm and cocoa. These new crops helped considerably, and by 1908 São Tomé and Principe was the world’s largest producer of cocoa. Cocoa still accounts for the largest export from São Tomé and Principe, but they are now far from the largest producer. According to online statistic aggregator Tilasto, they have fallen considerably, and from a high in of 11,300 tons in 1973, production fell to 2,778 tons in 2017.

In the 1960’s a nationalist group for the independence of São Tomé and Principe was established called the Movement for the Liberation of São Tomé and Príncipe/Social Democratic Party (abbreviated MLSDP/PSD). Such a group was not allowed to function with the borders of São Tomé and Principe, so they were established in Gabon on the African mainland. Once the Portuguese dictatorship was overthrown in 1974, the new Portuguese government worked with the MLSDP/PSD and brokered a transition to independence. On the 12th of July, 1975 São Tomé and Principe was granted independence and became its own country. The leader of the MLDSP/PSD, Manuel Pinto Da Costa was the first president.

Under the new government, most of the Portuguese Nationals fled the island nation and with them went a large number of the skilled personnel. Like many other nations do upon gaining independence or new government, Manuel Pinto Da Costa mirrored socialist policies, nationalizing many businesses and the plantations which placed a yoke on the ability to compete competitively, especially with outside nations. With the economy stagnate, over time it fell behind and in 1988 the International Monetary Fund instituted an economic reform. By 1991, the country had had enough and with a new constitution in place, a democratic election took place and as Da Costa withdrew his bid for office and a new president, Miguel Trovoada, was elected.

Under Trovoada’s leadership, the nation continued with the IMF’s economic reforms and the secret police that had been installed by Da Costa’s socialist regime was disbanded. Since then, São Tomé and Principe has enjoyed the democratic luxuries of freedom in politics, speech and economy. In 2018 the Ibrahim Index of African Governance ranked São Tomé and Principe at 12th of the 54 African countries in overall quality of governance.

Banknotes used in São Tomé and Principe under the Portuguese administration was done by the Banco Nacional Ultramarino. Upon independence, a circulating bearer check was issued which was quickly replaced in 1977 when they introduced the Dobra denomination. Dobra in Portuguese is translated as “Fold”, which is done to most banknotes in circulation worldwide. The profile of Rei Amador has been on most banknote designs issued since.