SUDAN

Pyramids at Meroe

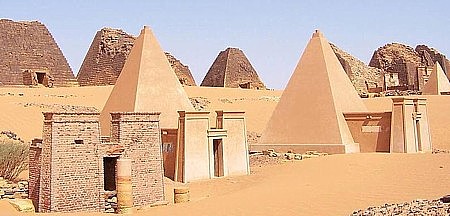

We are all familiar with the pyramids in Egypt, but were you aware of the pyramids located further south in Sudan? While not a secret, their existence has largely been overshadowed by their larger pyramid cousins in Egypt. Though they too have been looted and damaged in the past, they are still revealing treasures and giving up their history.

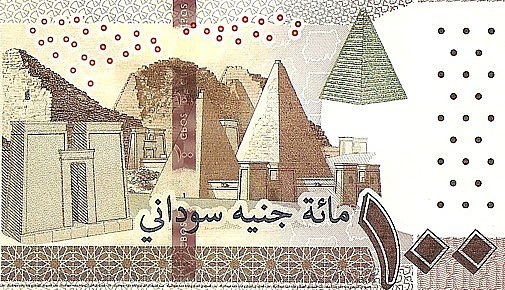

The pyramids in Sudan and their adjacent structures are reminiscent of the Egyptian pyramids, but they are definitely of a smaller size and considerably steeper than their Egyptian counterparts. These pyramids are attributed to the ancient Kushite kingdom by modern mainstream archaeology. The Kush region was located along the Nile, which is now Southern Egypt and Northern Sudan. Since the area was already known in general as Nubia, the pyramids are also referred to as the Nubian pyramids.

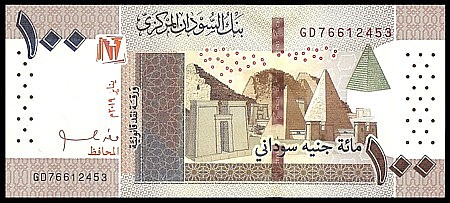

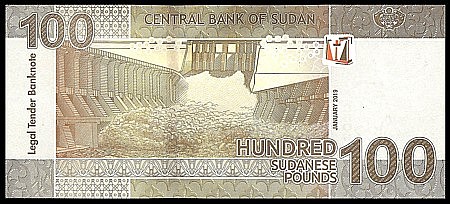

The Kush Empire followed much later than the Nubian kingdom, and was a strong political and military force in the area as far back as 2400 BC. As such, there is a long history of both conflict and trade between Egypt and the Kushite Kingdom, much of which has just recently come to light. The pyramids shown on Sudan’s banknotes depict the pyramids at Meroe, an ancient site in north-west Sudan. The Meroe pyramids date back only to about 300 BC and are from the last Kushite Kingdom.

The physical proportions of the pyramids in Sudan are significantly different from their Egyptian counterparts. The height of the Meroe pyramids ranges from only 20 to 100 feet in height, with stone block masonry of granite and sandstone that is set on a small base and an angle of 70°. Egyptian pyramids have much larger sizes, with footprints of as much as 5 times the area of the Meroe pyramids, and an angles ranging from 40° to 50°. Most of the Meroe pyramids are accompanied by adjacent temples initially thought to be used for offerings. Pyramids in other sites in Sudan are often quite small, some with only a three foot base. Earlier pyramids in Meroe were of the Stepped Pyramid design, but the pyramids built in the third century BC have the steep angled sides. While Egypt can lay claim to the largest pyramids, Sudan has them beat with numbers, more than twice as many as Egypt has.

While archaeologists still largely maintain that the Pyramids at Giza were erected as tombs, there is an awful lot of evidence, or rather a lack of evidence, that use as a tomb was not the case. In Sudan, many people are assured that the pyramids were in fact tombs, but again, this is not the case. For one, thing, these pyramids have no chambers, no passages, no hidden rooms. These solidly built pyramids were, however, burial monuments. The burial chambers were not inside, but were placed in front of the pyramids in what were initially thought of as temples. Rock steps lead down to the tombs where the interred were left on simple stone funerary slabs.

During the age of exploration, French explorer Frederic Caillaud was the European who chanced upon the pyramids in Meroe in April 1822. Being an astute explorer, he made detailed drawings of the pyramids in Meroe and published them in his 1826 book ‘A trip to Meroe on the White River’. Unfortunately there were less scrupulous explorers, those who were really mere treasure hunters, who beat a hasty and dusty track to Meroe soon after Caillaud’s book was published.

Chief among those treasure hunters was Giuseppe Ferlini, an Italian army doctor turned treasure-hunter. In 1834 Ferlini had teamed up with an Albanian treasure hunter named Antonio Stefani, and they made their way to Meroe with intent. It should be said that at the time, archaeology was in its infancy. With rare exceptions in the past, most people justified their archaeological plunder the name of their institution and country with little or no regard for neither anyone nor anything else but the hidden treasure. Thus we come to an understanding of Ferlini, who was, no matter how we may think of him now, simply a man of his time.

By the time he arrived in Meroe, Ferlini and Stefani had already scoured Frederic Caillaud’s book, whose detailed descriptions and Cailaud’s thoughts had helped Ferlini to make a decision along his route. Ferlini knew that the pyramids which were the most intact had a higher probability of still having treasure inside of them, and so he started with those.

Whether because he knew, or feared, that others would soon be following him in efforts to get at the treasure, or perhaps as a result of his military experience, we will likely never know, but Ferlini decided to make short work of his treasure hunting with modern conveniences.

Ferlini planted explosive charges in the pyramids and blew them up.

His ascertainment of the treasure locations was spot on. Ferlini was able to find a lot of treasure, though not within the pyramids themselves, but within the burial chambers located in front of the pyramids. To throw others off, he reported that the treasure was inside secret chambers in the top of the pyramids. Sadly, this led subsequent treasure hunters to follow his initial track and decapitate even more pyramids. With his newfound wealth, Ferlini hired a band of mercenaries to accompany him out of the area. His return to Italy made him not only rich, but famous. Fortunately a lot of the treasure was bought by King Ludvig I of Bavaria and the Berlin Egyptian Museum, where they can still be viewed. http://www.egyptian-museum-berlin.com/c33.php

In all, Ferlini and Stefani were responsible for the destruction of at least 40 pyramids in Sudan, all for the sake of riches. But Ferlini didn’t get it all. Subsequent excavations with more conservative efforts than Ferlini and Stefani’s were made, and it was found that the level of trade in Meroe was rather substantial. Items from upper Egypt were found, but also objects from the Mediterranean, including wine bottles (amphora) from Greece, Roman cups and even pottery from France.

Today the Meroe pyramids are a UNESCO World Heritage site, and while that gives them some protection now, the main damage has been done. Some of the smaller pyramids have been refinished recently, complete with their original plaster coating. While they give semblance to the original items from the distant past, when viewed together with the ancient and destroyed pyramids, you can’t help but be saddened by lack of respect that was paid them in 1834.

There are some who will lump the museums, universities, and other organizations with the treasure hunters, as the end result is that the treasure is still secretly removed and we will be lucky to see any of it, even in museums or online. But the level of getting to that treasure is what modern archaeological processes are best at. They preserve the edifices and bring us the historical information deduced from the systematic study during excavations.

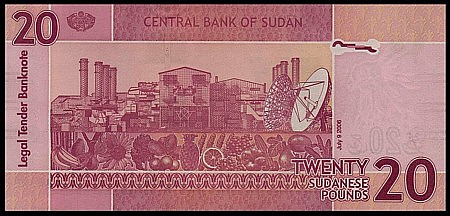

In recent years, the Meroe pyramids have been featured on some of Sudan’s banknotes, including the 20 Pound banknote issued in 2006 and again in 2011-17, and the 100 pound note issued in 2019. At this time the Central Bank of Sudan does not list the details depicted on their banknotes, however the Standard Catalog of World Paper Money curiously annotated the 20 Pound notes as “Machine and oil rig”. As a result there are a number on online sites that list the 20 Pound notes as showing ‘machinery and oil derrick’. The 100 Pound note shows the pyramids at Meroe as a larger central vignette on the front of the note, making the fact that they are pyramids easier to ascertain, and are already being correctly identified by several catalogers.