SURINAME

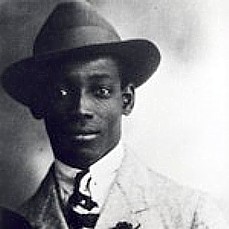

Anton de Kom

On February 22nd, 1898 in Paramaribo, Suriname, Cornelius Gerhard Anton de Kom (usually shortened to Anton de Kom) was born to Adolf de Kom and Judith Jacoba Dulder. His father was born a slave, but later became a farmer. Paramaribo is the capital and largest city of Suriname, located on the banks of the Suriname River along the Caribbean coast. The families surname was derived from a common practice among the slaves as taking the name of their owners, and spelling it backwards. Anton de Kom was able to attend school and was awarded a degree in bookkeeping, but the psychological aspects of slavery among his family and his fellow Surinamese, was still hanging over him.

Over the next few years, Anton had a series of short term occupations as he tried to find himself. In 1919 he worked for a company named Balata, after a local tree that bears fruit and whose sap is used to produce latex, an alternative to rubber. He left there in 1920 and travelled to Haiti to work for the Holland Transatlantic Commercial Society, but left there less than a year later to travel to the Netherlands. Anton must’ve needed money quickly, because he enlisted for a year with the military, and served with a light cavalry unit called the Hussars. Finding that army life wasn’t suiting him, he left when his enlistment was up, and in 1922 he went to the North-West coast of the Netherlands and worked for another year in The Hague. His next job however, would change his life forever.

While working for a coffee roasting company Reuser and Smulders, he met Petronella Catharina (Nel) Borsboom, a young lady whom he would later wed. Anton and Petronella Catharina Borsboom were married in The Hague on January 6th, 1926, with their first son, Adolph Antoine Gerhard (Ad) de Kom, being born the next year. Their family grew over the next four years, with Cornelis Theodore Julius (Cees), Antoine Jules Henny (Ton) de Kom, and their only daughter, Judith Jacoba (Judith) de Kom.

It was during this time that he had begun attending some leftist political meetings, becoming more and more involved in anti-Dutch colonial movements. Anton also started writing his book, “We Slaves of Suriname”. He did not go unnoticed by the Dutch authorities.

De Kom and his family left the Netherlands in the winter of 1932, sailing for Suriname. His name was wired to the Suriname authorities while he was en-route, citing Anton as ‘a communist agitator for the Anti-colonial League and the International Red Aid’. He was immediately under surveillance by the colonial authorities in Suriname.

Back in Suriname, Anton was faced with the deplorable situation that the general populace endured. Lack of food and acceptable shelter, oppressive colonial authorities and lack of healthcare were glaringly obvious. Anton set up a small firm advising contract laborers of their rights, and he began listening to the complaints of his neighbors and friends, eventually deciding that “Only when the people can participate in the colony, only then will they be able to end that situation, in which the small farmer is the daily slave of the direst need”. Having heard and seen enough, Anton wanted to have a public meeting in his father’s yard, but it was denied by the authorities. Instead, on February 1st, 1933, Anton, along with 1,000 followers, headed towards the Governor’s residence, but before they reached the grounds, the crowd was broken up by police and Anton had been arrested.

The populace started demanding the Attorney General to release Anton de Kom, and on February 7th, 1933, the people gathered in Government (now Independence) Square, near the governor’s palace, to demand Anton de Kom’s release. The police started to fire upon the crowd, killing two people, and injuring 23 more.

Instead of being released, Anton was exiled from Suriname, and sent to the Netherlands. He continued his work on his book, and began giving lectures on the state of affairs in Suriname. His book was published in 1934, but it was censored by the government. Still “We Slaves of Suriname” was a startling accusation of the colonial regime and the degrading situation that the Surinamese were left in. Anton had also resumed his association with leftist parties and became the editor of ‘Left Aim’, a labor and writer’s collective association. The Netherlands was suffering from heavy unemployment at this time, and this caused Anton to try to make ends meet by working for government sponsored work relief programs, and even as a travelling tap dancer. In 1939 Anton suffered from a nervous breakdown, and was institutionalized for three months. He was then released and placed on a governmental work crew to shovel snow.

Shortly afterwards World War II struck and the German Army invaded The Netherlands, occupying the country. During most of the war, Anton made a meager living giving lessons in English and Bookkeeping. However, his leftist leanings were still strong and he soon started writing for an illegal underground newspaper called “De Vonk”. The paper was generally of a communist bent and condemned the Nazi party with stories of atrocities against the Jews, and the local fascist groups made up of Dutch citizens.

The paper “De Vonk” was, of course, noticed by the German occupyers, and on August 7th, 1944, Anton was arrested by the Sichterheidsdienst, the intelligence agency of the SS and the Nazi Party. He was held for a short time in the Hotel Oranje (now a modern seaside resort along a sandy beach), but was quickly sent to a concentration camp in the southern Netherlands called Vaught. The camp held both male and female prisoners, many of whom were political activists like Anton de Kom. The prison was guarded by a division of the SS – the Totenkopfverbände (SS-TV), who ran concentration and extermination camps. Today, Vaught is a suburb of a city called ‘s Hertogenbosch. Many years later, Vaught was reportedly named the ‘Best Place to Live’ by a local Dutch magazine, Elsevier. But in 1944, Anton would have thought otherwise.

Later that year, in September, 1944, Anton was sent to Oranienburg-Sachsenhausen, in Oranienburg, Germany, where Anton was set to work in the Heinkel factory. This camp was used for political prisoners until the end of the Third Reich in May 1945. Heinkel was an aircraft manufacturer that was also a major user of the Sachsenhausen concentration camp labor, using up to 8,000 prisoners to build the HE-177, a long range heavy bomber.

The next spring, on April 24th, 1945 Anton De Kom died of tuberculosis at 47 years of age. He was buried in a mass grave in Camp Sandbostel near Bremervörde (between Bremen and Hamburg), a satellite camp of the Neuengamme concentration camp. In 1960, his remains were found and brought to the Netherlands, where he was buried in the Cemetery of Honors in Loenen. On January 1, 2011, Loenen merged with Breukelen and Maarssen to form Stichtse Vecht, situated north of the city of Utrecht.

In 1971, 26 years after his death, Anton de Kom’s book, We Slaves of Suriname, was published in an uncensored version. It became a success, examining the psychological effects of the past slavery issues continuing into the modern era and concludes that as a result of slavery his people have inherited a sense of inferiority that the colonists have perpetuated. Anton’s personal experience comes through, letting the reader know his personal anger and hatred of the social extremes his people had to endure. In 1974, the Surinamese started meeting with the colonial Dutch government asking for liberation. Independence came on November 25th, 1975, and Suriname was its own nation, governed by its own people.

It is due in part to Anton de Kom’s actions in both The Netherlands, and in Suriname, that liberation was eventually achieved. His book helped to raise the self-esteem of the Surinamese people, emboldening them. Anton de Kom helped to plant the seeds of knowledge that the sufferings of the people were not only wrong, but were also able to be righted by the people themselves, gaining their liberation from an oppressive ruling class.

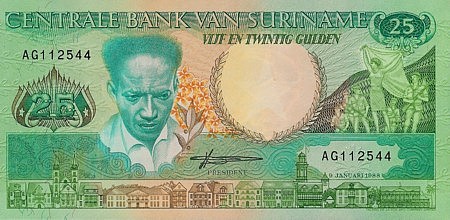

Anton de Kom has had many posthumous honors awarded to him, including the renaming of the University of Suriname to the Anton de Kom University of Suriname, being listed as # 102 out of 202 persons as the greatest Dutchman, and a square bearing his name in Amsterdam, along with a statue of Anton. He was also on several issues of banknotes, including this one below, showing him on the front in portrait, and on reverse at his father’s house, shortly before his arrest trying to talk to the government about the welfare of the people.