TEA BRICK

Tea Brick

Spices were a long time coming to our tables. There was an immensely lucrative spice trade going on for centuries, but the spices were so rare and valuable, that only a very few could afford to consume them and only the wealthy could really afford them regularly. For others, such as traveling merchants, spices were a convenient form of currency where monies and precious metals were not standard in many parts of the world. They could be measured out and spent in many places, and ancient accounts of rent being paid with pepper are commonplace. Even as late as 1973, Prince Charles was given a tribute of a pound of pepper in Cornwall. Nutmeg, pepper, garlic, and even tea was so prized that there were many wars fought for control of the trade. Currency is defined by Merriam Webster dictionary as a: circulation as a medium of exchange b: general use, acceptance, or prevalence. Spices, it seems were indeed a common worldwide currency.

In the early to mid 19th century, China had long had a lucrative trade with Britain, especially with its tea exports. China was then a tightly controlled country and its practices in tea cultivation, far inland, was kept from the Europeans, who were major buyers of tea. China sold tea and other luxury items, but by decree of the Chinese government, only silver was accepted as payment for its exports. This was too expensive for the British, so they developed an alternate trade with the merchants. The British began selling opium to the Chinese for its medicinal and recreational purposes. The Chinese would pay for the opium in silver, and then the British would take a portion of its profit for opium and purchase tea. This was very profitable outcome for the East India Company, but when the Qing government realized what the effects of opium were having on its country they decided to try to put a stop to it by ending opium trade. This resulted in what became known as the Opium Wars. China was soundly beaten by the British forces and had to make concessions: Hong Kong Island was now owned by the British Empire, new cities were opened up throughout China for British trade, and of course opium sales resumed.

But the British were looking ahead and were thinking that the Chinese could easily cultivate their own opium, which would ruin the trade imbalance. So it was decided: Britain would strike first and develop its own tea cultivation in the Indian Himalayas, which were similar to the regions that Chinese teas were grown. But first Britain needed to seize tea plants and seeds, which posed a problem only one man, a famous horticulturist, could solve: Robert Fortune.

Robert Fortune was employed by the East India Company and in 1848 traveled to China to steal their tea and secrets. He needed to disguise himself as a Chinese person, adopt Chinese dress and hair styles, and learn a rudimentary form of Chinese language. He looked a little odd, and spoke with an accent, but he had the benefit of having a forged royal Manchurian seal, a trusty translator, plenty of fortitude, perseverance, and luck. He traveled throughout China’s tea producing region taking samples and keeping them alive in portable terrariums that were recently developed called a Wardian Case. Seeds and plants could survive the year’s long journey from China to India where the Teas would be cultivated on Himalayan lands owned by the East India Company. Previous attempts had all but failed, but the Wardian case ensured that the plants would survive in their own environment until they reached their final destination.

Robert Fortune was a great botanist, with a steady job and a series of books published. But the prospect of becoming perhaps a great explorer, securing vast wealth for himself, the East India Company and Britain and all the accolades that were sure to follow were enough to convince him to embark on his journey. Together with his trusted Chinese merchant guides, he was able to convince the local peoples that his odd mannerisms and strange looks and accent were merely due to his being from the royal court in the far south of China, a man of prestige that few would have ever encountered before. He was repeatedly given unfettered access to all the plantations he encountered and was able to not only get first hand views on cultivation, but also advice from the naïve owners on how tea was made. He was also able to take plant and seed samples, ostensibly for the royal court, and send them on their way instead to the plantations in India where they were eventually cultivated.

In addition to the profitability, availability, and eventual price drop in teas, cultivation by the British in India produced better quality teas and ensured that they were not tainted as was the tea from a green tea factory on the Yangtze River. At this factory, two distinct poisons were found to be introduced into the tea: Ferro Cyanide, typically used to dye paints, and Gypsum were added to aid in the coloration of the tea to convince the British that the teas were consistently green in color.

Robert Fortune’s name was indeed fitting, for he had great fortune in his ability to skirt all the trade inspections, most of the bandits and all of the legal authorities due to his and his companion’s cunning and luck. In all 12,838 seeds were sent to India and were growing by the end of his trek in 1851. In the next 50 years, Indian tea exports would to rival all of China’s.

Harvested tea in China was often formed in the most unique manner as a Tea Brick. A tea brick is either whole leaf or powdered tea in a block form. Tea pressed into brick form could be used to steep in water to make tea, be eaten as a food and provided a convenient form for transportation, storage, and even for trade and currency purposes. Those teas pressed into bricks which were meant to be shipped very long distances, or to be used as currency were often combined with blood and sometimes even yak manure to help them maintain their form from being handled repeatedly. The first known account of tea used as a form of currency was penned by the French missionary Evariste Regis Huc, known popularly as Abbe Huc, who traveled into the region in 1844-1846. He noted that the bricks were used to pay wages as well as purchasing goods.

Unusual as it seems to us, tea was a form of currency, and tea bricks used as currency were very popular in the outlying regions of China including Tibet, Mongolia and Siberia. Their substitution for coinage was popular due to the nomadic cultures and lack of shops to purchase wares and food from. Tea bricks could be used as currency and eaten and drank in times of need. In Siberia it was also used as a form of medicine for reparatory ailments. In Tibet, the tea bricks were known as “eighths” (brgyad-pa) because their worth was long pegged to eight Tibetan Tangka coins. At other times possessions and properties were sold in amounts of numbers of tea bricks or tea cakes.

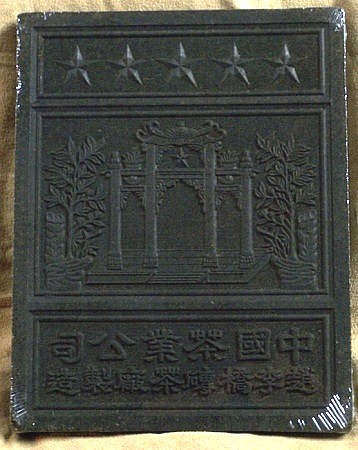

Tea bricks were known to be in various forms, shapes and sizes. Most were about 8” x 10” x1”. Depending on the type of tea and how it was compressed could be anywhere from two to five pounds. Their value, like any commodity, was dependent on quality and rarity. Darker bricks with fewer stalks were favored over lighter colors with woody stems. Quality coupled with the distance they traveled set the local price. It was sometimes found that lower quality teas were disguised as high quality by adding soot to the mix to darken the tea bricks color. When the hydraulic pressed were introduced in China, the bricks were able to be pressed with embossed images, typically a temple and dividing lines to aid in breaking the brick in to pieces.

Tea bricks were used as a form of currency in rural Asia up until the Second World War. Teas in brick forms are sold today for dinking, but are primarily souvenir items. Most are Pu-erh teas from Yunnan, China, which need to be aged a year for proper taste, but the older it is the better the quality. Ancient tea bricks are very rare as they were typically consumed at some point. Modern tea bricks usually have eight Chinese characters on the bottom where older hydraulic pressed bricks had seven characters.

This tea Brick was purchased at an import store, and it states that it is not intended for consumption. It is a modern souvenir of a forgotten method of trade and consumption.