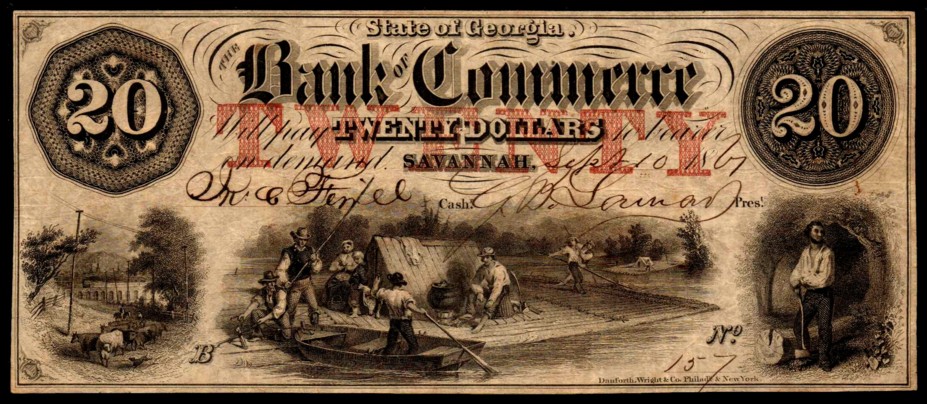

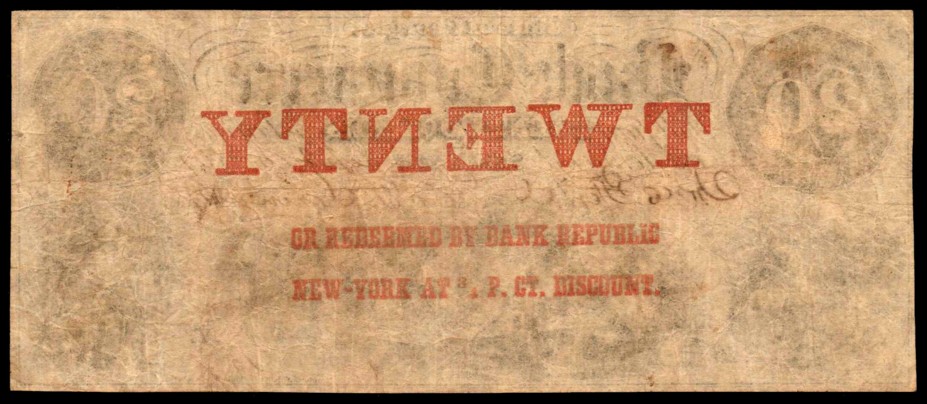

Georgia 1861 $20

The Bank of Commerce, Savannah

Here’s another great note from the Bank of Commerce in Savannah, Georgia, featuring the signature of G. B. Lamar.

Gazaway Bugg Lamar, or G. B. Lamar as his signature is written, was born in Augusta, Georgia in 1879 to Basil and Rebecca (nee Kelly) Lamar on October 02, 1798. He would make a name for himself as a banker and businessman. In 1821, G. B. Lamar married Jane Meek Cresswell Together they had six children.

In the 1830’s they moved to Savannah, where G. B. Lamar continued his work in commerce, including insurance, warehousing, banking and shipping. He had ordered a ship to be pre-fabricated in England and shipped over to Savannah, GA, in sections where it was assembled and launched. The SS John Randolph, the first American Iron Hulled Steamship, 100 feet long and 22 feet wide, was launched in Savannah, Georgia on July 09, 1834. It became a great success on the river trade. There is a memorial plaque on Bay Street in Savannah, on the east side of Savannah City Hall.

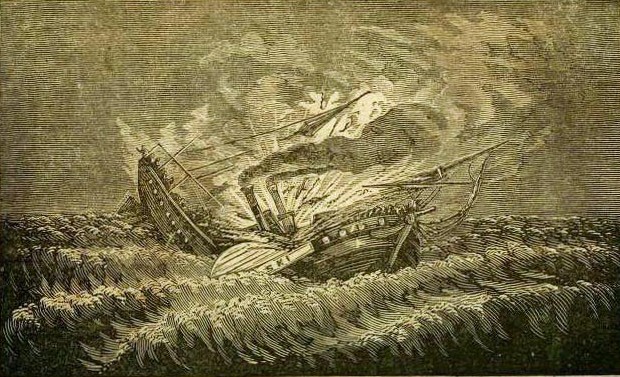

Then the family met with horrific tragedy on the night of June 14, 1838. G. B. Lamar and his family were embarked on the steamship Pulaski, carrying between 187-197 passengers and crew. They were about 30 miles from the North Carolina coast heading north when the boilers exploded, killing all but 59. Among the survivors were G. B. Gazaway, who miraculously floated ashore, his son Charles and his daughter Rebecca. The remaining members of his family were all lost.

The disaster was significant not only due to the number of souls lost at sea, but also due to the findings of the review board. The boilers were apparently operated incorrectly, and as a result, there were strict regulations regarding the operations of boilers placed in effect.

Ironically, the Pulaski was made from the remains of the old Steam Packet (Mail Carrier) Home, which on October 09, 1837, was hit by a large storm, waves breaking over the deck and snuffing out the boilers. The Captain had to ground his ship 65 miles north of Ocracoke, North Carolina in order to try to save it and its 135 passengers and crew. The ship began to break up, and though some survived, 95 people perished. The public was astonished and demanded that something be done to prevent such losses of life at sea. The government then instituted more stringent laws and regulations for safety on ocean going vessels.

In January 2018 the wreck of the Steamboat Pulaski was believed to be located off the coast of North Carolina. In May of 2018 the conclusive evidence was brought up from the wreckage: a candlestick holder and a token, both of which were stamped stamped “SB Pulaski”. The SB is an abbreviation for Steam Boat.

At 41 years old, G.B. Lamar married Harriet De Cazeneau in 1839, and together they had another five children. By 1846 Charles Lamar had grown up and was trusted to run Gazaway’s businesses in Georgia on his own. G. B. Lamar relocated the rest of his family to Brooklyn, New York, where he helped to launch a new business, The Bank of the Republic, dealing primarily with southern trade.

He trusted his son, but he disapproved heartily of his son’s association with the slave trade. Charles was the owner of a slave ship, Wanderer, and was working to revive the international slave trade, which was abolished in the United States in 1808. The Wanderer was the last ship to be reported as bringing a cargo of slaves from Africa to the United States, in November 1858, when the Wanderer docked at Jekyll Island, Georgia with 303 slaves. The government prosecuted, but did not win the case against Charles Lamar. His father’s views on his son’s activities in the slave trade were clear in a missive he wrote to his son:

“…An expedition to the moon would have been equally sensible, and no more contrary to the laws of Providence. May God forgive you for all your attempts to violate his will and his laws.”

Nevertheless, his son was the one in charge of his interests in Georgia while he was away. Then, as is still too often now, morals did not interfere with business.

All went rather well for G. B. Lamar, until the Civil War broke out. For a short while, he was even an agent for the South, and organized a shipment of 10,000 muskets to Georgia to prepare the southern forces. In May of 1861, he left New York and returned to Savannah, to take personal control of his businesses there during the hostilities. While back in Savannah, G. B. Lamar became the president of the Bank of Commerce, which issued these two notes, bearing his signature. He seems to have been in a rather large position of influence, as he had been an advisor to several members of the Confederate government, including Georgia Governor Joseph Brown and CSA President Jefferson Davis. As a financial advisor, he recognized that the method of borrowing money to fund the war was too costly, and he was a strong advocate for maintaining a purely defensive posture. The South, unlike the North, did not enact an income tax for funding the war, and issued many bonds and promissory notes.

In correspondence with Tom Lamar Coughlin, author of Rebels In My Tree, he points out that the weapons were in fact declared obsolete by the Federal Arsenal, and that the purchase was made in the open. In the atmosphere immediately preceding the Civil War, such purchases would indeed be legal, including their transport to the southern states, despite the question of their intended use for Southern support.

In October 1863, G. B. Lamar called a meeting with all the bankers in the Confederate States in order to address the state of Confederate issued currency. He had little influence, and as we know now, it was very late in the war for such a consideration.

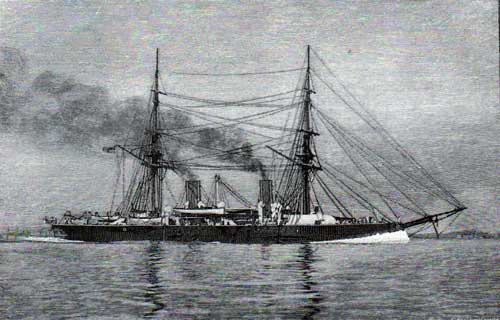

Throughout the war, G. B. Lamar traded overseas in guano, cotton, and tobacco, which required him to create a company specifically to run the Union naval blockade. In all, he was quite a successful merchant even during the war. But when Union forces under the command of General Sherman entered Savannah, G. B. Lamar was quick to acquiesce and he took the required Oath of Allegiance for the Union. Given his willingness to take the oath, and his history of being in New York as a successful businessman, he was pardoned for his rebel allegiance during the war. However, all was not going well for G. B. Lamar. Soon after the assassination of Lincoln, he was implicated as a suspect and arrested, being held in the Old Capitol Prison in Washington D. C. for three months. Once the charges were released for a lack of evidence, he was free, but found that his goods, primarily cotton, were under the control of the government. When he tried to claim them, he was again arrested, this time for theft of government property and bribery of a government employee. He was shortly granted a commuted sentence by President Johnson.

For the rest of his life he pursued his claim for compensation for his confiscated goods and, in 1874, he won a lawsuit against the US government, being awarded $580,000. Even though this was the largest sum ever awarded to a claimant, he was still wanted to pursue for more damages. He would go to his grave without obtaining more from the government, passing away on a trip to his daughter’s in New York City, in 1874. In his will, he left instructions for his family to continue pursuing the government for his lost property, and leaving $100,000 for a convalescent home to be constructed for aged and infirm Negroes in Savannah, Georgia.

The bank cashier, John C. Ferrill, was a longtime resident of Savannah and served for five sessions as an alderman (city council member) from 1858 through 1873.

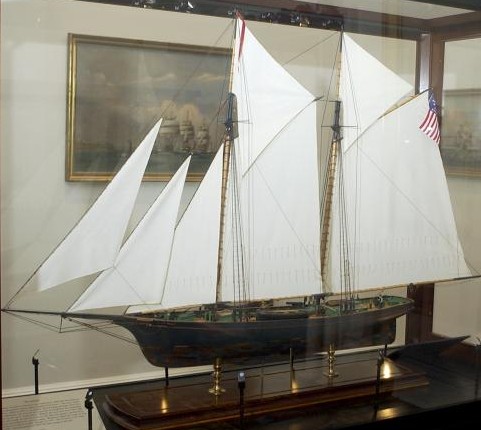

Note on the Ship Wanderer:

The ship was infamous as a slave ship and was the last reported slaving ship to operate before the civil war. The failed attempt to prosecute the owners and operators incensed many peoples in both the North and South. The incident even caused then President James Buchanan to press for more aggressive policy towards the illegal slave trade. Less than a year afterwards, the southern states had seceded, and the Civil War began. The Wanderer was seized by the Union Navy in 1861 near Key West, Florida. To prevent her falling into the hands of Southern forces the Wanderer was used in a variety of ways and ended up as a hospital ship. She was sold off after the war and was lost off the coast of Cuba in 1871.