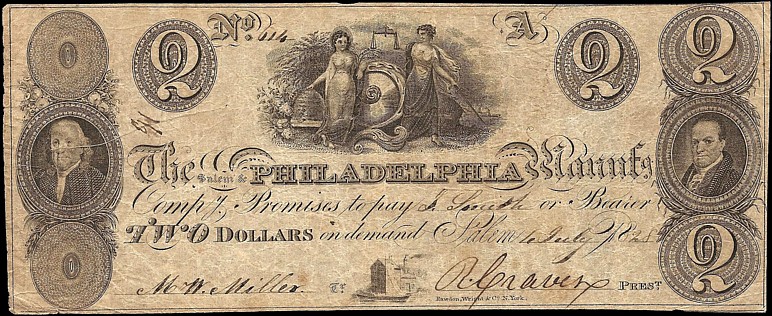

New Jersey 1828 2 Dollars

Salem and Philadelphia Manufacturing Company

Salem, New Jersey is a small town within the county of Salem, and according to the 2010 census, has approximately 5,150 people. The area was first inhabited by the Lenape tribe of Indians, and when the first immigrants came into the area, the Lenape’s were able to keep much of their lands and sovereign power by offering to trade peacefully. The Dutch, Finnish and Swedish immigrants were able to exist peacefully with the Lenape, but their forts and settlements in the area were not wholly successful. Salem was the first permanent settlement by European immigrants to New Jersey.

Situated along the Delaware river, Salem was first laid out by John Fenwick in 1675 and was initially incorporated until 1798, and then again in 1858 as Salem City. Built in 1735, the Old Salem County Courthouse is the oldest active courthouse within New Jersey.

The first emigrants built grist and sawmills, which spurred business in the area. Tide-mills were soon erected in Salem and nearby areas, a type of mill which uses the power of the incoming tide to fill a reservoir behind a mill. The mill can only be put to work after the water level outside of the dam has sufficiently dropped during the ebb tide, allowing the water in the reservoir to flow back out through a gate and onto the power mill. Wind mills were also erected and in 1682 a new sawmill was in place in Salem. With all the manufacturing capabilities these different mills offered, the economic prosperity of Salem soon bloomed. Foreign and local trade brought in goods to the town to process and led to shops and markets opening in the area as the area grew in population and prosperity. As a result, Salem was able to become an official Port of Entry in 1682, which brought in custom houses which collected taxes from the ships trading in the area.

For itself, Salem was able to offer not only the processing through the mills, but could export a variety of animal pelts, lumber, hardware, and produce. In partnering with neighbors in new York and Philadelphia. A shipyard was erected, where small ships were made and put to sea, and glassworks factories were also placed into production throughout the early years.

The years following the Revolution brought an economic downturn and prices were so low that there was very little incentive to farm. But in the early 1800’s those farmers who remained started to specialize in their crops, and with the aid of fertilizers began to increase their crop yields.

Salem was largely populated with Quakers, whose influence helped to lower the incidents of slavery in the area. In 1830, there was only 1 slave in the area, while 1,400 Free Blacks were part of the population of 14,155 people. The Quaker influence and the number of Freed Blacks made the area a destination for escaped slaves.

But what of the Salem and Philadelphia manufacturing Company? It was noted in an early legal document that the company was first known as the Salem Steam Mill and Manufacturing Company, and in 1828 changed the name to the Salem and Philadelphia Manufacturing Company. Other than that, I could find nothing about the company’s location or what they manufactured. The names on this particular note, M.W. Miller and R. Craven, of whom I found out nothing leads me to believe that there may have been some illicit activity with this company and the notes it issued. This is given more credence with an 1828 report from the New Jersey Attorney General.

On November 11, 1828, the Attorney General issued a report to the New Jersey Legislature concerning the Salem and Philadelphia Manufacturing Company, wherein the “…objects of the said corporation were solely for the purpose of manufacturing and without any banking privileges, and that it was expressly provided in the act of incorporation, that said company should not carry on banking operations”. The report was enough to have the Attorney General ordered to take legal measure to investigate the Salem and Philadelphia Manufacturing Company and to revoke their charter.

In 1829 the Attorney General’s office made inquiries in the area but was not able to find that the Salem and Philadelphia Manufacturing Company was in fact in violation of carrying on banking operations. “There was no evidence that the notes of the company, in common form of banknotes, were in circulation and had been paid out by the agents of the company in the discharge of debts, and purchase of machinery and in other modes-but no proof could be found that the company had discounted notes, or performed any of those acts which are appropriate to banking operations.” It was posited that there be no further action without positive leads in the case. The report later on found that the owner of the company had died, and the cashier has left the state, and that there were neither banking nor manufacturing operations and that the mill and property have been sold.

Then, four years later, in the Niles’ Weekly Register (Volume 43 – September 3, 1832), published in Baltimore Maryland, it seems that these notes were quite well known as worthless: “It seems that bills of the infamously famous swindling shop, called the “Salem and PHILADELPHIA Manufacturing Company,” are still sometimes offered as money. One fellow at St. Louis had $2,750 in them. He was arrested and committed to jail for trial, and, we hope, will be punished.”