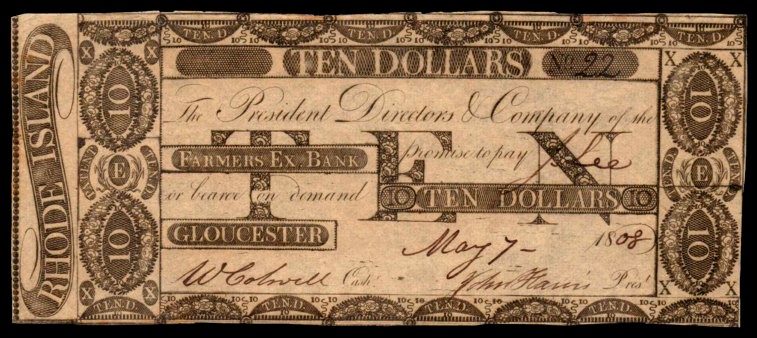

Rhode Island 1808 $10

Farmers Exchange Bank

The Town of Glocester (now Gloucester) is located in northwestern Rhode Island and was established in 1639. The chiefs of the local Native American tribes sold the land to Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island. Gloucester was originally a part of Providence, RI, but in 1730 it was separated and became its own town. Gloucester remains a rural community surrounded by various lakes, ponds and forest. It was named after Frederick Lewis, the Duke of Gloucester, and the son of King George II of England. On April 16, 1806, the city was divided in half, with the northern half adopting the name of Burrillville and the southern half keeping the name, but changing the spelling to Gloucester. While the name change would have been adopted by the printing of this banknote, it still carries the old spelling.

Into this town came Andrew Dexter, Jr., born on March 28, 1779 to his parents, Andrew Dexter, Sr., and Mary Newton. He grew up in Providence, Rhode Island, and received his education there as well, at what was then known as Rhode Island College, and was later to become Brown University.

The younger Dexter also studied law under his uncle Samuel Dexter, who was a rising politician in the Massachusetts government. After serving a period as his uncle’s secretary, he obtained his Bar License from Suffolk County, MA and entered into association with some contacts he had made while serving his uncle.

This association quickly manifested itself as the Exchange Office, which was a brokerage firm that specialized in the trading of banknotes. At this time in history, there were no federal banks that issued banknotes, and the paper money that was issued were essentially promissory notes from banks and companies that were operating without much legal oversight. The Exchange Office that Dexter and his partners operated was taking advantage of the situation by purchasing banknotes from banks at a discount and selling them later for a profit. This could be easily done due to the fact that as one person may have a banknote from a bank in, say Boston, MA, then travelled some distance, and needed to use that banknote, the shop clerks may not be too keen on trading it in for the full value. In fact, there were often discounts in varying amounts, based on the issuing bank/company’s prominence and influence in the area. So the Exchange Office would purchase the banknotes for a little more than the shops would exchange them for, and sell them later, most likely in the areas that they were issued in and could get the full amount for; A nice racket.

By 1805, Dexter had risen to the position of Superintendent of the Exchange Office, but the wave of his endeavors was starting to crest. In 1806, he started his acquisition of several rural banks such as the Berkshire Bank in Pittsfield, MA. He would soon have a chain of such banks throughout the new nation, including the Farmers Exchange Bank, which incorporated in 1804, in Gloucester, Rhode Island. Obtaining these banks was a great foresight, as he recognized that having many of the banks he was dealing with would provide him with a greater profit. Once in control of his many banks, he was also in control of issuing their banknotes. A lot of banknotes.

The method often used for controlling the issuance of banknotes and curbing fiscal irresponsibility was to back them with precious metals, such as gold and silver. If Dexter had studied finance instead of law, perhaps he would have known better, but as it happened, there was precious little of the precious metals backing his banknotes. That in itself is not necessarily a bad thing. Our current banking system is based in the fiat model, where there is no backing, just the public’s acceptance of the banknotes and coins as money. Nevertheless, without knowing when to stop printing banknotes, it becomes a slippery slope that many have slid down.

Dexter bought up a lot of land in the Boston area and announced that he was going to build a new Exchange Office and an opulent hotel that he felt was lacking in a city as important as Boston. At an estimated cost of $100,000 to build, it was a grand enterprise for a grand city. Dexter had thought it through and was convinced that the cost would soon be offset by the rents from the hotel, and the rooms in the Exchange Office. Things moved fast and in 1807, they started construction, quickly looming seven stories high and with exquisite decorations inside and out. But what Dexter hadn’t counted on was politics.

In 1807, then President Thomas Jefferson passed an embargo act, which was in response to the wars in Europe and the European nations confiscating American ships and cargo and pressing their sailors into service. The embargo lasted two years and put a deadly strain on American trade. Ships literally rotted in their docks in the northern states while southern states had their crops rot in the fields. While the embargo did spur a rise in demand for American made goods, trade essentially ended, and with the absence of trade, there was an absence of investors in the Exchange Office building in Boston. Dexter, who had been so used to getting his way over the past few years, thought nothing of making his own investments: He simply printed more money. As trade floundered nationwide, his beautiful building kept on with its construction, all funded with a glut of banknotes issued from Dexter’s many banks: a sure path to inflation if not checked in time.

It didn’t take too long before word got out about the carelessness of Dexter’s funding. Merchants throughout Boston soon began to refuse payment with any paper money from a bank that Dexter owned, and people began trading in their banknotes for coins, specie and other, more trustworthy, banknotes from credible banks. As a result, Dexter’s banks began to suffer. In 1809, the Farmers Exchange Bank in Gloucester, Rhode Island had the distinction of becoming the nation’s first chartered bank to fail. The precious metals that were supposed to back the more than $650,000 in issued banknotes, was a paltry $86.48.

As more and more of his banks folded, Dexter fled to Canada to ride out the storm. He returned to the United States in 1812, settling in New York. When his father in law died in 1816, he inherited a new fortune and he purchased land around what would later be Montgomery, Alabama. His wife died in 1818, the same year the ill-funded Exchange Office and Hotel in Boston burnt to the ground. Andrew Dexter, Jr. remained in Montgomery, Alabama until his death from Yellow Fever in 1837.